Hero’s Journey, Shmero’s Journey

“Why do you hate the Hero’s Journey?” nobody may be asking. But one thing about a hero is that he always delivers.

“Why do you hate the Hero’s Journey?” nobody may be asking, but boy do I have some thoughts about it that I’m going to share with you today. Thank you to everyone who voted on this topic!

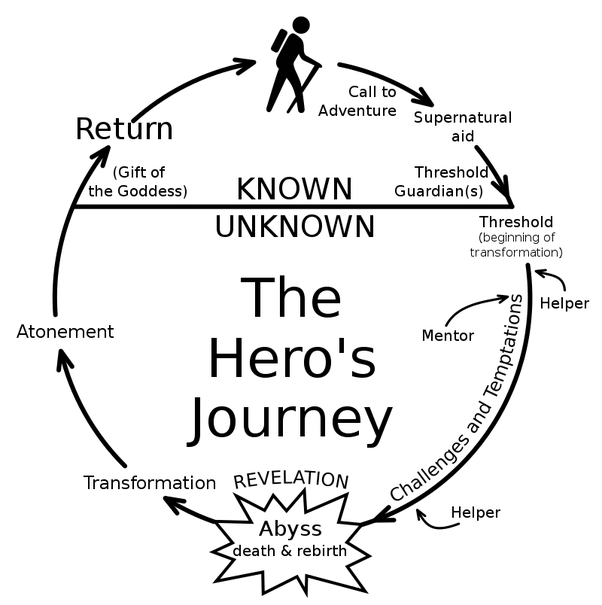

I’ve called myself a ‘Hero’s Journey Hater’ before, mostly as a joke. The truth is, I just dislike it, not only in concept but often in execution too. Over the last few years of immersing myself in writing and bookish communities, reading craft books and other stories, I’ve found myself standing more solidly on this opinion, and have finally decided to sit down and run through some of the reasons why. I’ll be focusing on Joseph Campbell’s traditional hero’s journey for this post.

Disclaimer: Obviously if you like the traditional hero’s journey, more power to you. Go off and slay beasties! Write and read it to your heart’s content.

This substack is called ‘ella has thoughts’ and so thoughts I must have.

Is there actually such a thing as a ‘monomyth’?

"There is a certain typical hero sequence of actions which can be detected in stories from all over the world and from all different periods of history. Essentially, it might even be said that there is but one archetypal mythic hero whose life has been replicated in many lands by many people." — Joseph Campbell (The Power of Myth)

Campbell’s monomyth is presented (by himself) as an understanding of some kind of universality of storytelling, but… there really isn’t such a thing as a story structure that is true for each and every society or culture, is there? What about stories of heroes who don’t return home in the end? What about heroes who aren’t straight, allosexual men? Campbell seems to have chosen a few narratives that supported his idea, dismissed narratives (or didn’t even consider them in the first place) because they didn’t fit the pattern he was trying to find between them.1

Therefore, I take issue with the very idea of ‘the monomyth’.

Did Joseph Campbell think women couldn’t be heroes?

I suppose that depends on how you interpret some of the things he has said about women, the hero’s journey he identified, and the way women fit into that journey. Joseph Campbell is quoted as having said “Women don't need to make the journey. In the whole mythological tradition, the woman is there. All she has to do is realise that she's the place that people are trying to get to." Does this mean women don’t need to go on a hero’s journey because she’s already a hero? Or because… well, why would a woman want to do heroic things? Or because women are prizes, the reward men/heroes come home to? Hard to say.

What’s not hard to say, however, is that the hero’s journey very much is based on masculine, male-centric mythologies from male-dominated cultures, most often with male heroes, and thus patriarchal patterns and scripts.

Throughout Campbell’s book, Hero with A Thousand Faces (1949), Campbell consistently refers to the so-called hero with the masculine pronoun “he”, and very infrequently mentions the possibility that a hero might be female. He also assumes that the male hero is heterosexual, and not only that, but must be allosexual and experience sexual attraction, and vice versa.2

If one reads 1000 stories based on male heroes with little perspective on the stories and experiences of other groups and cultures, then goes on to say that “Women don’t need to make the journey”, it might make another (read: me) think that the hero’s journey isn’t made for anyone who doesn’t fit the masculine heroic ideal.

“The mystical marriage with the queen goddess of the world represents the hero's total mastery of life; for the woman is life, the hero its knower and master.” - Joseph Campbell

Yikes.

In the hero’s journey, women often play passive, stereotypical, or quite small and secondary roles—and that isn’t even mentioning how often they’re quite absent from the whole narrative.

Campbell also seems to believe that ‘initiation’ is more difficult for boys than it is for girls, because ‘life “over-takes” women’, whereas boys must intend to become men. It seems the passivity of women in life and in myth either extends to or comes from their own bodies, and it also seems that he “accepts the Jungian doctrine that the decisive moments in a woman's life are physical, and in a sense, inflicted on her: deflowering, conception, and childbearing.”3

All of this gives me what I still hope the kids are calling the ‘heebie jeebies’.

Tracing the selective roots of “Heroism”

When we look back on some of the older heroic stories, such as Homer’s Iliad, we can see that most of the heroes in these narratives have been men—and not only that, but if we stand there in the past and look forward to now, the majority of our heroes have been cisgender, white, and able-bodied, too.

Joseph Campell’s hero’s journey is both a reflection of a dominant social scripts and belief system, and goes on to reinforce it. He noticed a pattern and pushed it forth as not ‘a’ but ‘the’ monomyth, and it has since gone on to be taught in schools and in writing courses. If you’re a writer, you might have heard of it five-hundred times before, because it’s taught as a story structure that anyone can fill out and create their own story from.

Even if we do have a more open, diverse, and varying idea of “heroism” now, the hero’s journey itself is quite a hegemonic idea.

This heroism uplifts and actively valorises strength, courage, dominance, taking action, and individualism. Traditionally, these qualities are seen as masculine, while traits such as empathy, cooperation, nurturing, and fragility, are often seen as feminine.4

Even in cinema today, namely superhero movies since the superhero = hero equation is distinct, we can see how these movies follow gendered socio-cultural scripts, scripts that perpetuate and idealise hypermasculinity and other harmful gender practices, and which appear in some of the earliest heroic tales. Consider those roots traced.

The hero’s journey very rarely promotes a “hero” I actually like.

Personally, I’m not really into threats and violence, but many “heroes” engage in this behaviour in order to “do what needs doing”. And listen, I’ve been known to support fictional women’s wrongs. Sometimes a punch to the face is cathartic! But a lot of “heroes” are people lying to their friends, not giving people enough information to give informed consent, making decisions for the collective without listening to the collective, beating up and killing “bad guys” who are also victims (cough, cough… stormtroopers, anyone?) and very rarely depict anyone with a disabled body like mine.

It could be argued that, well, the hero was in A Situation that Made It Impossible To Do Anything Else, but I think that’s removing the creator from their creation, which isn’t something I think we can do—not wholly, anyway. Writers make the choice to put their characters in those Situations. And oftentimes, these Situations don’t quite hold up to scrutiny and explain the hero’s choices. But that’s getting into the gritty stuff, and I’m not here to complain about [REDACTED].

Individualism is Might

As I mentioned earlier, the traditional/typical hero’s journey is quite individualistic, and often when the story does seem to be pushing for communitarianism and collective teamwork, the narrative again puts the hero in A Situation where they are forced (or feel like they’re forced) to act alone to save the day.

This narrative framework does not allow for the diversity and complexity of having to work within a collective, nor does it endorse the value and greatness of acting as part of a team and not being wholly self-reliant and hyper-independent. It also doesn’t allow for a lot of ambiguity of experience and perspective, which would come from this diversity of community.

Which Power Ranger is "the hero"? Which Evangelion pilot is "the hero"? You can't decide that easily, because in a lot of Asian fiction, multiple heroes work together as a team. The team itself is "the hero", but the "hero" being a team is not something ever discussed by Campbell, who heavily focused on examples of heroes from Greek mythology. - RACHAEL LEFLER (How Monomyth Theories Get It Wrong About Fiction)

Who can be a hero? What qualifies as heroic?

Logically, I think we all want to say “anyone”. But I don’t know, man. I’m feeling pretty left out right now. When we look at the hero’s journey and how it’s often employed in storytelling, we get heroes who are often literally or figuratively super-human, who are moral paradigms, and who succeed through bravery, courage, and perseverance.

And listen, I know we technically have disabled heroes.

But what about people who can’t persevere? As someone with Ehlers-Danlos and chronic pain, I can’t persevere so hard that I find myself at the top of a mountain, but something tells me that image of me giving up doesn’t seem very heroic to many. MY inability to push through my pain and ultimately do my body more damage is seen as failure.

I can’t grit my teeth and push myself through a dislocated shoulder or hip just because some evil guy is in my kitchen holding my cat hostage. I mean I’d love to, don’t get me wrong. The minute I can stand up again, that evil guy is gonna get a lifetime referral to a therapist and whatever other help he needs.

Heroes don’t “need to lie in bed and hope for their medication to kick in. They don’t seize up and need help getting off the couch. They don’t walk, scrunched over like a thousand-year-old crone as they wait for their muscles to loosen up.”5 They are not like me.

“Those with chronic pain are not heroes in our speculative fiction because we expect our heroes to overcome their physical limitations and save the day. Even Yoda, with his cane and his hunched back, is able to wield a lightsaber like a youngling when the need arises.” - GEMMA NOON (Give Me Heroism or Give Me Death)

And sometimes, when they are like me, they still uphold and endorse a very able-bodied and masculine view of heroism, so the representation falls flat. They might fall into the ‘super-crip’ trop, so the representation falls flat. They might have a disability superpower, so the representation falls flat. The narrative might attempt to be empowering, but because it ultimately rests on and perpetuates ableist rhetoric that values able-bodied performance over accommodations, knowing your limits, and acting within the boundaries of your disability, the representation falls flat.

The Hero’s Journey as Criteria

Okay, so maybe this reason is more personal. But it still stands! I don’t like story structures and how they’re often presented in writing spaces as formulas or things to be followed. I think publishing has a problem with representing diverse voices and diverse stories, and so the “does your story follow the hero’s journey?” or “look at the three-act structure to make sure your story is story-ing” feels like it’s potentially aiding that. Stories should come in all shapes and sizes and styles, but if I’d gotten a dollar for every time I’ve seen the hero’s journey touted as the best thing ever, I’d have enough to buy a Nissan S-Cargo, which makes me really sad because I both ironically and unironically want that car.

Don’t get me wrong, I can see how it might help writers as they learn the craft of constructing a narrative, but I wish it were sold as that more often than it is. I know, I’m probably riding a petty horse. Still! The hero's journey is a very rigid structure that follows a set of steps that the hero must go through in order to succeed. It’s a story beat sheet that feels like paint-by-numbers to me, likely because I’ve seen it so many times in so many books and media. It’s become too predictable, too noticeable.

Ultimately, it’s an observation about the structure of a narrow selection of stories that has then been turned into not only a template, but that has also used as an evaluative tool or a list of criteria that a story “has to hit” for it to be “good”, much like the three-act structure. And I don’t like that.

That, and I’m just not sure how or if we can or should divorce it from its roots.

An Acknowledgement

I’m also sure that many of my reasons for disliking the hero’s journey aren’t exactly inherent to it. For example, the simplistic themes that often appear in a hero’s journey story may not be necessarily dictated by the structure. They’re more like symptoms or side effects, brought on through years and years of people replicating it and the social scripts we’re raised to follow. As with anything, it’s got more to do with how it’s used, and in this case, how the story is written. I can still enjoy media that uses this structure. I like Star Wars, for example (not that I don’t have my criticisms).

I’m sure someone, somewhere out there has followed the hero’s journey story structure and created a narrative which takes all of my complaints and has turned them into strengths. Surely.

I have to ask though, if such a narrative exists, is it still a hero’s journey, or is it something else entirely? Do we still call it a hero’s journey even if it isn’t Campbell’s idea of a hero’s journey? Can we call it something awesome, like Super Mega Foxy Awesome Hot Hero’s Journey?*

What do you think we should call it?

RACHAEL LEFLER. How Monomyth Theories Get It Wrong About Fiction

SPENCER MCDANIEL. The “Hero’s Journey” Is Nonsense (2020)

MARY R. LEFKOWITZ. MYTHOLOGY: The Myth of Joseph Campbell (1990)

VETTERLING-BRAGGIN, MARY, ed. 'Femininity,' 'Masculinity,' and 'Androgyny': A Modern Philosophical Discussion (1982)

GEMMA NOON. Give Me Heroism or Give Me Death (2018)