Breaking The Spell: Why "It's Fantasy!" Isn't an Excuse

In which I say fantasy probably still needs to make sense and can be judged through real-world lenses and understandings.

Hello, friends.

This week I had thoughts™️ about Fantasy, and asked myself the question: is it fair to think about made-up worlds with made-up people in made-up situations through the lens of our real-world social systems, experiences, and ideologies? Let’s think about it!

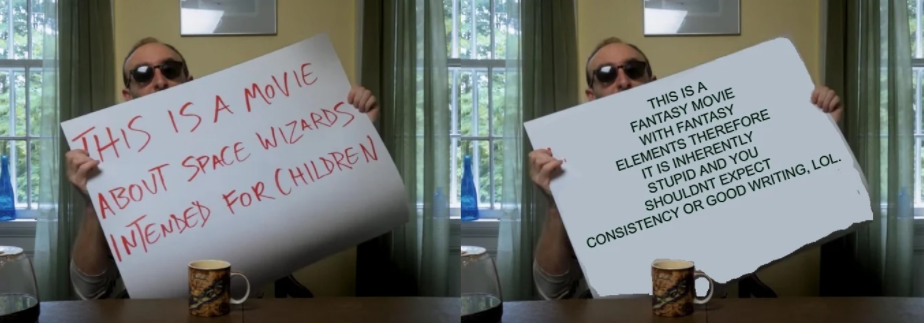

Anyone who is active in any bookish space such as Goodreads or Booktok may have come across critical reviews or opinions and replying comments that state something along the lines of “We have to remember, it’s fantasy” or “It’s fantasy so nothing is real”, often followed by some really awesome zingers like “so you’re a big dumb dumby”.

Judging Fantasy

Fantasy books, like any other media, should not be exempt from critical thinking, observation, and discussion, and the fact that it is “made-up” or “set in a different world with different rules” doesn’t change that. This is my thesis. Boom. 👏 That’s the end of this essay, but if you’d like to tune in next week—

Ha. When have I ever been succinct? Let’s get further into it.

Problematizing and critical thoughts about fantasy works should not be dismissed on the basis that the world is fantastical; Readers should be able to take a hard look at who or what is included, excluded, erased, challenged, and upheld in a text, as well as the reasons behind those choices made by the author. Why? Fantasy works, like any other works, are products of our world and our socio-cultural systems.

I will be using “think critically” both for its actual meaning, but also as a shorthand for thinking about a fantastical work through the lens of reality.

“While fantasy can indeed be mere escapism, wish-fulfillment, indulgence in empty heroics, and brainless violence, it isn’t so by definition — and shouldn’t be treated as if it were.”

— Ursula K. Le Guin (Some Assumptions about Fantasy, 2004)

I understand, to some extent, the lack of desire to look at fantasy (and any of its sub-genres like sci-fi fantasy, romance fantasy, etc) with a critical eye, because for many people it’s wrapped up in this idea of escapism and pleasure and when you begin to look critically at something, it can be more difficult not only to remain in that state but to remain in complete love with a text you enjoyed. We want to protect our joy, comfort, and pleasure. Maybe for the sake of keeping some peace, I want to say fine, don’t think critically, but don’t dismiss those who do and who try to engage in discussions about what they’ve noticed as if they’re only trying to be negative. Maybe these two modes of consumption can co-exist. On the other hand, I would like to make the argument that critical thought is needed, because fantasy is not immune from perpetuating harm. To dismiss and disparage the act of critically thinking about a text is to sell the work and the author short, to deem them unable to hold up, and to deem those who do choose to think critically as being overly harsh, daft, and harmful (as if it is an attack, or is inherently a call to some form of action).

To many, thinking critically about a text is fun. It’s a way to legitimize a text by thinking about its elements and analyzing how they work, why they’re there, and what they’re doing. It can be done at the same time as loving a text—the two are not mutually exclusive, even when the discussion is critical.

What is perhaps a little ironic is that some pleasure-readers engage in critical thinking all the time, maybe even without realising that’s what they’re doing — just look at all the theories and thematic observations about the work of Tolkien, how he wrote from experience and was exploring themes of heroism and humanity. Look at all the theories and observations readers have put together about works by prolific Romantasy writer Sarah J Maas. Look at all the commentary on Romantasy novels and how they uplift women’s voices and perspectives in a genre (fantasy) that has long been male-dominated. I see this all the time in reviewer spaces like Goodreads, subReddits, and Booktok: the same readers who tell critical reviewers they’re being “too serious” and “thinking too deeply” to refute discussions about the work’s potential problematics, are some of the same readers with an online presence partially dedicated to why the same book is a masterpiece and that they’ve picked up seven clues to support a theory they came up with.

So it seems to me that critically thinking and making critical observations about works of fantasy is in fact okay, fun, and productive, so long as it’s not criticizing or speaking “negatively” about the work, and so long as it’s not “bringing politics into it”, as if all art and the act of consumption isn’t political.

Disclaimer: None of the works or authors mentioned here are being endorsed or promoted by me but are being used as examples for the discussion topic.

J. R. R. Tolkien on logic and immersion:

I’d like to begin with a basic argument about craft before I think about some of the social justice elements.

J.R.R. Tolkien, the author who many see as the inventor of modern fantasy, says the author "makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is "true": it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside. The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or the art, has failed.” He described the effect of being pushed out of a narrative’s logic, back out into reality, looking at the story as though “from outside.” While Tolkien is perhaps a little more critical of the need to or act of “suspending disbelief” than I am, I agree with his general sentiment that, even when they’re fantastical, worlds and stories need to have some sort of internal logic or consistency to them in order to effectively keep readers inside the Secondary World.

So, there. You heard it from someone much cooler than me.

“It’s fantasy!” doesn’t absolve a text of the need to make some sense—because even if the not making sense is intentional, that means it paradoxically does make sense.

“Read fantasy, ignore reality!”

(A new and funky slogan I’ve come up with to capture the general sentiment that is pushing back on people critically thinking and discussing fantasy works).

This attitude toward fantasy doesn’t make sense to me because it ignores all of the ways fantasy works can marginalize, exclude, harm, reflect oppression, or maintain and legitimize misconceptions, dominance, and injustice through systems of power.

“It’s fantasy! It’s not real!” lacks compassion because what is a fantasy for some is very real for others. Not to mention, speculative fiction often draws on real-world ideas and systems as inspiration, so we can’t entirely divorce them.

Even Star Wars is influenced by the real world. George Lucas has spoken openly about how the Vietnam War was one of the biggest influences of Star Wars and has said “…the political and social bases [of Star Wars] are historical”1. It’s somewhat of a very basic example, seeing as there’s nothing subtle about the historical allusion to Nazi Germany in the series, but the point stands.

But even when an author doesn’t state or believe that they’ve been influenced by anything around them, can that ever truly be the case?

Fantasy continues to minoritize—to pass over marginalized characters, voices, and stories. It continues to reflect oppressive systems—to forget women exist, to subject them to ridiculous levels of sexual assault and a systemic stripping of agency, to privilege the agency, strength, and stories of men, to forget disabled people exist.

Are all these examples an active choice on behalf of the author? And if they were—why? Where do these depictions and inclinations come from?

Nothing is made in a vacuum.

In the same way that saying “romance is written for women, by women, and is inherently feminist” assumes that women cannot be sexist, saying “it doesn’t have to make sense or be realistic because it’s fantasy” also assumes that no ideology or logic from our real-world went into the creation of the text. But nothing comes from nothing.

Fantasy is produced in this world, in this environment which is built on capitalism and many other harmful systems and ideologies such as sexism, racism, ableism, homophobia, classism, and more. How can we act as though fantasy, or any product of this environment, has total immunity from all of the pitfalls of those systemic issues and their intersections?

“Fantasy is a literature particularly useful for embodying and examining the real difference between good and evil. In an America where our reality may seem degraded to posturing patriotism and self-righteous brutality, imaginative literature continues to question what heroism is, to examine the roots of power, and to offer moral alternatives. Imagination is the instrument of ethics.”

– Ursula K Le Guin (Some Assumptions about Fantasy, 2004)

The belief that fictional fantasy narratives are able to be completely divorced from the world we all experience is unfounded. According to the literary critic and theorist Robert Scholes, no author has imagined a world free of connection to our world, “with characters and situations that cannot be seen as mere inversions or distortions of that all too recognizable cosmos.”2 Imagination is a process that enables people to distance themselves from the present real world and to explore alternative possibilities.3

Can we look at a feminist fae through our understanding of real-world feminism? Can we look at shadow-wielding stoic badass through our understanding of real-world toxic masculinity? Is there any other way to look at and think about what we consume?

Fantasy exists in an alternative position to reality; there is no one without the other. We enter texts with our preconceived ideas, beliefs, and thoughts. Despite this, some readers can go into a fantasy text and simply believe what it’s telling them and read “brain-off” if they so choose, but when someone asks how or why is this faery man a feminist, and challenges the reasons the text gives, it’s not logical to push back on that questioning by reiterating that “the faery man is imaginary”.

Taking what we consume as is and without question, and dismissing more active modes of consumption and engagement, promotes a kind of anti-thinking notion that also doesn’t allow for a few key things: the fact that what is imaginary comes from people who are not imaginary (that is to say, real, actual humans), and that passive consumption and escapism is a privilege.

Everything is subject to the external forces of our real world, and when the narrative framing is telling the reader that something is desirable, romantic, empowering, etc. it can have the effect of normalizing, fetishizing, commodifying, and endorsing harmful social scripts.

Take the supercrip trope for example, which plays with the common belief that disabled people could do everything everyone else does if only they worked hard enough—in a novel that relies on a disabled person being “empowered”, unquestioningly, through this hard work in which they adapt to the world but the world does not adapt at all to them, the framing here can have a few effects; It could suggest to readers that this is truth because it aligns with rhetoric we most often hear in real life, and it can suggest that maybe the author actively or subconsciously believes this ableist rhetoric without understanding the harm it can and does do. As a disabled reader who has had to battle this rhetoric my whole life, this fantasy is not fantasy, it’s a bit of a nightmare, and I don’t have the privilege of “escaping” into the text when it’s parroting my reality back at me. Alright, it's an entirely made-up world of made-up things, so why is the world being made up of unchallenged ableist ideas? Why is that the fantasy, the thing being imagined?

In this way, fiction (yes, even fantasy) is connected to the reproduction of ideology, because media that is indistinguishable from real life trains consumers to identify it directly with reality.4

When works of fantasy reflect real-world ideologies, the line between “it’s made-up” and “the work or the author may be [accidentally] perpetuating or endorsing this” blurs.

Intention, Context, and Reflections

I spoke earlier about Star Wars and its influences, as stated by the creator George Lucas. I’m going to call that “external context”, that is, the context which is external to the text but nonetheless can inform my reading and interpretations of the work.

One thing that genuinely fascinates me is asking, what is the context of this thing I have consumed? What is the author saying in interviews? How is the marketing material positioning this text? What messages could that be conveying? Is it legitimizing and endorsing anything potentially harmful?

These questions are important to ask because they help me think about the reasons behind the choices made by the author – using my example of the supercrip trope earlier, if the author is critical of this trope outside of the text, I’m more inclined to believe that they were engaging with it intentionally and were not intending to sell the narrative as one of empowerment and inspiration, even if that was the impact of the text on me as the consumer. If, however, the creator is endorsing this narrative as empowering, inspiring, and aspirational, then I’m definitely engaging in some major side-eyeing and will be acknowledging that in any reflections and discussions.

If we take into consideration the external context of a work, we can see, at least in part, what the intent was, and we can better understand what the creators wanted us to take away from the thing that they created. We can interrogate what impact this has—how many people will read the supercrip narrative and subscribe to it unquestioningly because their favourite author and all the marketing around the text told them it’s aspirational and “inspiring”?

As a writer, I am always asking myself some variation of “what inspires me?” What do I like? What do I enjoy? Why do I want this plot point to happen, or this character to get with that one? Why does my protagonist do this instead of that? This will not, of course, mean that I never misstep and write something that someone will dislike or rightfully take issue with, but I wanted to mention the author process of thinking critically and thinking about the things that already exist in reality, which often begins at the ideation stage and continues throughout the actual writing. Choices are being made, intentionally and unintentionally, informed and uninformed. At the risk of repeating myself: works of fantasy are being created by real people with real thoughts and beliefs. These are inevitably going to make their way into what they create, unintentionally or not.

Oh, the irony.

I just wanted to briefly talk about how ironic it is when marginalized voices speak critically about fantasy works, saying “Hey, I read this and think it’s perpetuating/endorsing the systemic silencing and dismissing of xyz voices”, the reply of “No, actually, you can’t judge fantasy by real-world logic” is also doing that silencing and dismissing. It’s doubly ironic when the text being discussed is being held up as a paradigm of inclusion of said marginalized community. Amazing.

And now, the conclusion.

To critically think, make critical observations, or critically discuss a fantasy work is to do so with the understanding that the work is fantasy and that it is not wholly divorced from reality. I doubt people forget that what they’ve read is fantasy, which adds a bit of an urge to do a silly-goofy laugh whenever I read it as a defense of a text. In fact, many fantasy works are simultaneous in asking readers to both escape reality for a time as well as take in lessons and learn about the complexities and challenges of the real world5 and the people within it.

I believe that storytelling is one of the coolest and most useful tools humans have for helping us understand the world around us, who we are, what life can be, what things we can do to survive and thrive, what things may stop others from doing the same—even when these stories are told through the lens of a unicorn, or set on an alien planet, or confined to a magic school. We read stories, and we relate to and empathise with characters and their situations. Why should we refuse to think about how fantasy connects to reality and to empathise with real people who raise discussions about it?

I spoke in the beginning about the desire and inclination to protect the pleasure we get from reading something we love by refusing to acknowledge the potential problematics raised by other consumers. It’s understandable. But what isn’t understandable to me is doing so by actively dismissing and minimizing the people who are willing, wanting, and often have no choice in doing that work (think: a disabled reader who picks up on ableist language). My desire to escape into a book does not outweigh my responsibility as a human being to have compassion for those who have different experiences than I did, do, or will have.

Publishing is a capitalist enterprise, and its purpose is to make money. The books it puts out are products of our dominant oppressive systems like capitalism, racism, ableism, classism, and homophobia—systems that fantasy books are often about fighting.

The only way for us to help fight them is to take our understanding of these connections into the world we live in and be loud about it. Or at the very least, not discourage the people who want to do so.

What do you think?

Thank you for reading this post! If you got anything out of it, why not subscribe?

Klein, Christopher. "The Real History That Inspired "Star Wars". HISTORY.com.

Fredericks, S. C. “Problems of Fantasy.” Science Fiction Studies 5, no. 1 (1978)

Zittoun T, Gillespie A: Imagination in human and cultural development. 2016.

Adorno, T., & Horkheimer, M. (1944). The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception

Webb, Caroline (2014) Fantasy and the Real World in British Children's Literature, The Power of Story