Risky Non-Partisanship

Speaking truth and seeking justice outside the bifurcating boundaries of partisanship

On a recent Sunday morning, having recently celebrated mass at his church in the Diocese of San Cristóbal de las Casas in the Mexican state of Chiapas, Father Marcelo Pérez was gunned down by two members of a local drug cartel.

Father Pérez, an Indigenous Tzotzil priest, was known for his peace advocacy in a region that has experienced increasing violence due to drug trafficking. His activism made him a repeated target, at times with a bounty on his head, who had to be moved to different dioceses for his protection. Previous attempts to kill the outspoken priest by sabotaging his car had failed and it seems that Father Pérez lived under the constant threat of violence with one priest saying, “He considered death as a possibility for denouncing this situation.”

At his funeral, the retired Bishop José Raúl Vera López recalled how Father Pérez understood his ministry.

Father Marcelo took special care of the poorest, the weakest, the most unprotected, and he protected them from abusive people, from powerful people, from people who feel they own society and the land and who do not mind harming the lives of others to enrich themselves or to acquire greater political power to get everything they want… He was especially concerned about people whose dignity was damaged by unfair treatment from authorities or from abusive people. This, dear sisters and brothers, is what the Lord Jesus Christ tells us today,

Cardinal Felipe Arizmendi, the man who ordained him, recalled Father Pérez as someone “committed to justice and peace among Indigenous peoples” who “never got involved in partisan politics but always fought for the values of the kingdom of God.”

Father Pérez was unknown to me until I read about his recent murder. Given that at least 52 Catholic priests have been murdered in Mexico since 2006, he’s surely not the only courageous clergy person risking their life on behalf of the poor. But it was the cardinal’s claim about the non-partisan nature of Father Pérez’s advocacy which really grabbed my attention.

I’ve experienced a bit of blow-back over the years for my outspoken opposition to Donald Trump. You can imagine some of the reasons his supporters get frustrated when the former president’s pernicious character flaws and dehumanizing rhetoric are pointed out, but I think a major one has to do with the power of partisanship. Because I regularly make the case publicly that Trump represents a particular menace to the vulnerable neighbors Christians are called to love, the assumption is that I must therefore be for whichever candidate the other side is running against him. And so, rather than engaging with the critiques of their candidate, Trump’s supporters begin attacking President Biden or, more recently, Vice President Harris.

One way to think about partisanship is as a specific set of rules for political engagement. One of these rules requires that principled opposition to one candidate means endorsing the other candidate. So, for example, while some centrist and progressive Christians rolled their eyes when their conservative counterparts organized for Trump, we now have similar organizations for Harris. (I’m on the record sympathizing with the friends who’ve joined Christians/Evangelicals for Harris even as I’ve felt no compulsion to join them.) The partisan framework struggles to imagine political engagement that is not, itself, partisan. If there’s something dangerous about that political team then you must join this political team.

The partisan rules are thoroughly utilitarian. If one party’s candidate or policy is really a threat, then the only legitimate option is to sign-on to the other team. You may not like everything about your new team, but what other way is there to resist the danger represented by the other side? As someone who has long been convinced that Trump is an actual threat to vulnerable people and whose disdain for democratic norms will only add to their vulnerability, I know how convincing the partisan framework is.

In August, Tyler Huckabee, writing about Christians/Evangelicals for Harris, reflected on the pull to align with one party against the other. Like me, he’s sympathetic to these groups but finds himself unable to join. Why?

My politics don’t conveniently map onto either political party. I think most Christians feel the same way. Heck, I think most people feel the same way. This isn’t because I’m one of those faux-sanctimonious centrists who see staking out the middle ground between Republicans and Democrats as a worthy goal in and of itself. It’s just that a lot of things I’d like to see done politically are not being touted by either party.

Huckabee goes on to list addressing climate change, ending the war in Gaza, and other priorities which he doesn’t believe either party will prioritize as reasons he can’t fully affiliate. This makes him a “Christian with particular and occasionally even contradictory politics who is forced to make a strategic vote in this two-party system and will ultimately pull the lever for the candidate who seems more likely to hear my side out than the other candidate is.”

What the non-partisan stances taken both by Huckabee and, more vulnerably, by Father Pérez reveal is that a Christian can reckon very seriously with the precarious nature of our circumstances without going all in with either party. The benefits of remaining outside the partisan gates are pragmatic and existential. By choosing to support certain policies or causes over a personality or their party, we maintain a degree of influence unavailable to the already committed. Also, this distance allows us to maintain our distinction as citizens of the kingdom of God, an identity which does not place us above the fray but leads us deeply into it, friends and allies with those most overlooked in the partisan framework.

Refusing the bifurcating choices presented by partisanship leaves us open to being misinterpreted as milquetoast moderates or afraid-to-rock-the-boat centrists. Oh well. As Father Pérez’s courageous witness reminds us, the follower of Jesus already has a foundation strong enough from which speak truth and seek justice no matter how costly the response.

(Sources: LA Times, American Magazine, Catholic World Report, BBC, and Catholic Review.)

Plundered Updates

Have you read Plundered? Or are you far enough along to think that it’s worth recommending? If so, it’d mean the world if you could leave an Amazon review to help others find the book. Thanks!

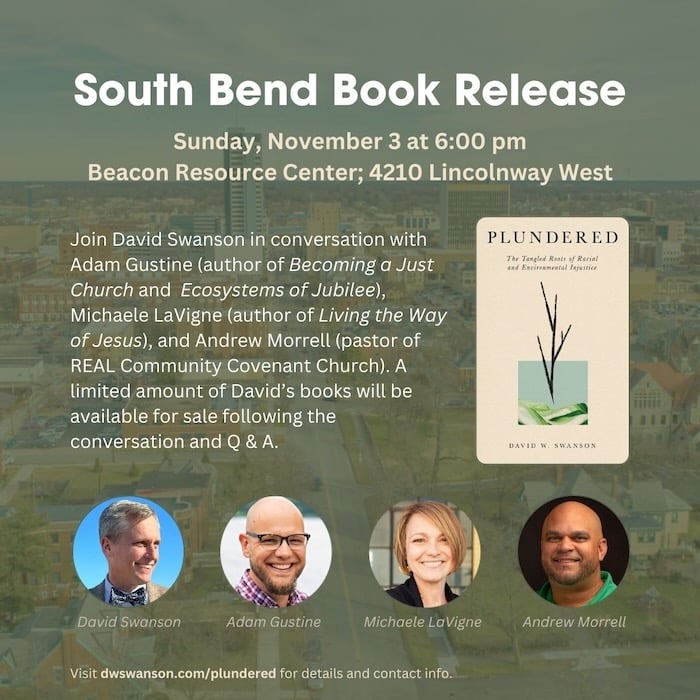

Do you live within driving distance of South Bend, Indiana? Come join these friends and me next Sunday evening!

My friend Alexis Busetti has been kind enough to have me on her podcast a couple of times and it was great to join her again to talk about the book.

What Do You Call Your Pastor?

An article I wrote for our denominational magazine about pastoral titles and the assumptions behind them was recently published.

As members of the majority, white people have the privilege of not reflecting on our culture, of thinking of our experiences and assumptions as culturally neutral and universally normal. This is the social dynamic that distracts me from noticing someone else’s cultural assumptions. It’s what allows white people to step into a sanctuary full of racially and ethnically diverse worshipers and delight in the diversity without noticing that the cultural assumptions guiding the length of the service, how verbally responsive the congregation is, and so on are all rooted in white norms.

The View From Here

If you’ve read the first chapter of Plundered, you might recognize this view of the Museum of Science and Industry as seen from the Bobolink Meadow. Isn’t autumn the best?!