The Ark in Space

“I’m forever blowing bubbles.”

Someone with whom I used to work in the decade or so that I dwelled within an often cold and sterile corporate ecosystem had a marvellous theory about people and art. Actually, he had several, and that he did so was one of the reasons I managed to tolerate working in an area in which I had an exponentially declining interest for quite so long.

One of these theories in particular, the one relevant to the 1975 Doctor Who serial the title of which is above, was about “being in sync” with something. He held that it was okay to buy a book or a video (this was a long time ago) in a hurry and put it on a shelf and forget it. To not experience it for months or even years. Decades, at a push. You’d bought it for a reason, and it would eventually call out to you when you were “in sync” with it.

The flip side of theory was that you could get this wrong, and if you did, you might end up not liking something, or not getting the most out of it, and purely because you engaged with it at the wrong time. Timing is important. You don’t want to be woken up to something too soon.

The Ark in Space was the second serial of the first Tom Baker series of Doctor Who, and was broadcast early in 1975. Its second episode was seen by 13.6m viewers, which was not only Doctor Who’s highest audience for ten years, but a viewing figure which gifted the show its highest 20th century placing in the weekly chart (#5).

It remains second most watched non-ITV-strike impacted Doctor Who episode ever made. No one has yet ever quite taken down The Web Planet from 1965 - although a handful of C21st Christmas specials have come within a margin of error of it - and it remains worth noting that such is the changed nature of viewing figures this century that while Tom Baker was the first (and only) Doctor of the old century to hit #5 on the hit parade, every Doctor this one has strolled through that barrier at least once.

Nevertheless those numbers were a remarkable vindication of a story that had had, if not a troubled production, then a troubled genesis. A story simply called that, Space Station, was submitted by writer Christopher Langley in very late 1973, just as the production diarchy of Barry Letts and Terrance Dicks was giving way to a new team of producer Philip Hinchcliffe and script editor Robert Holmes. As time went on, Holmes began to feel the work Langley was doing didn’t work, and the brief for the story was then given to another writer, John Lucarotti. Lucarotti had written for Doctor Who in its earliest days, but not for ten years, and was apparently recommended to Holmes’ by Dicks, who had been working with Lucarotti on his and Letts’ SF side hustle Moonbase 3.

Lucarotti lived on a houseboat, usually moored off Corsica, which he moved to other Mediterranean islands as he liked. This reportedly made contacting him during the writing process difficult. When his scripts arrived at the Doctor Who production office, their passage apparently also impacted by a postal strike, Holmes found them to also be not to his taste. With little time until the serial had to go into studio, Holmes decided to rewrite them himself.

Holmes re-wrote the serial extensively, perhaps from scratch, retaining concepts and set pieces from Lucarotti’s. Lucarotti was paid in full for his finished work but was not credited on the serial. His scripts would have to wait a few decades before having Tom Baker finally unleashed on them.

This was the first, but by no means the last, time Holmes did this as Doctor Who’s script editor. He predecessor Terrance Dicks had also often had to rewrite scripts heavily and it seems that this had perhaps been accidentally obscured from Holmes by the simple fact Holmes himself was one of the few writers Dicks did not habitually significantly redraft.

There were also issues in post-production. There was a scene in the second episode in which the character Noah, possessed by the insectoid Wirrn (Holmes’ replacement for Lucarotti’s amoeboid Klef) and transforming into one, begged to be killed before he lost his humanity.

Writer Holmes had always indulged the side of Doctor Who that inclined to horror but now fully in control of the series’ creative direction, he’d gone further than ever before. Hinchcliffe debated the matter with his own boss, Head of Department Bill Slater (who had originally suggested Tom Baker be cast as the Doctor) before excising the material as unsuitable for its timeslot. Even now Hinchcliffe describes it as the first big decision he took as a producer. A watershed moment. If you’ll pardon the pun.

Despite this, the transmitted serial drew complaints for its violence and horror content. Mrs Mary Whitehouse’s campaign against the series as unsuitable for children was entering a new phase. (One often conducted through the barrister John Smyth QC, later revealed to be a prolific violent and sexual abuser.1 This perhaps indicates how seriously we should take Mrs Whitehouse as a judge of character, and an arbiter of what is ethically sound.)

Nevertheless the production team was so pleased with the serial and its overall reception that it was edited again, being condensed into a single omnibus edition, broadcast at 6:35 pm on 20 August 1975. It reached a thoroughly respectable 8.2 million viewers at the height of summer.

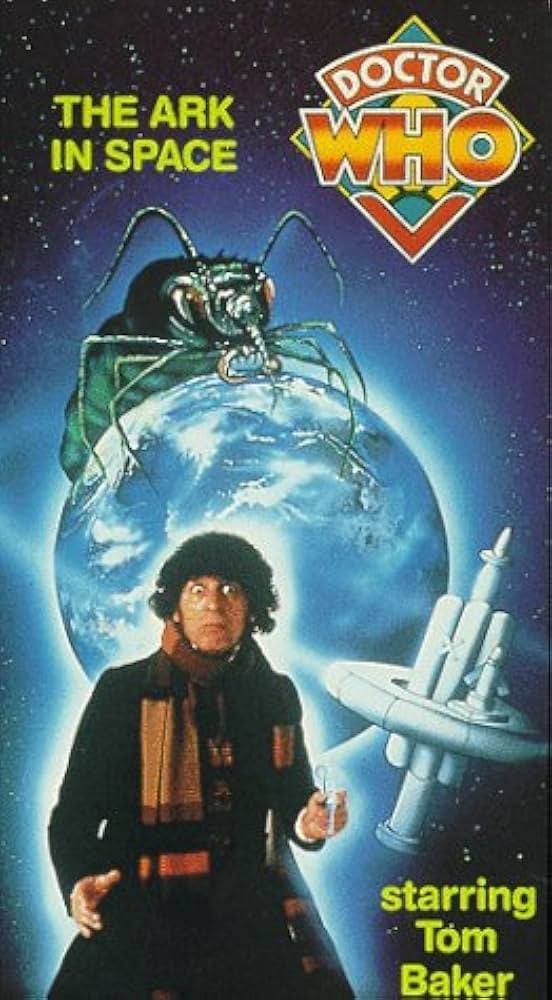

It wasn’t the last controversy for The Ark in Space, although the later one was a more minor affair. The story was released on VHS in Australia in 1989, despite never having been released in the UK. At the time only a handful of Doctor Who serials were available on VHS and fandom was hungry for further releases. Concerned letters and articles appeared in Doctor Who Magazine, and something approaching moral panic enveloped Doctor Who fandom. It was another kind of repeat. The story was released in the UK five months later. With this cover.

This is when I saw it. I had followed that controversy closely in DWM and noted the magazine’s tendency to prefaces its title with “the superb”. Nevertheless, when its VHS release finally hit the local rental shop, it had to get in line behind the first Dalek serial. Which was my first chance to see William Hartnell’s first Doctor, outside of the tiny clip at the start of The Five Doctors. Also, you know, Daleks. Daleks are brilliant.

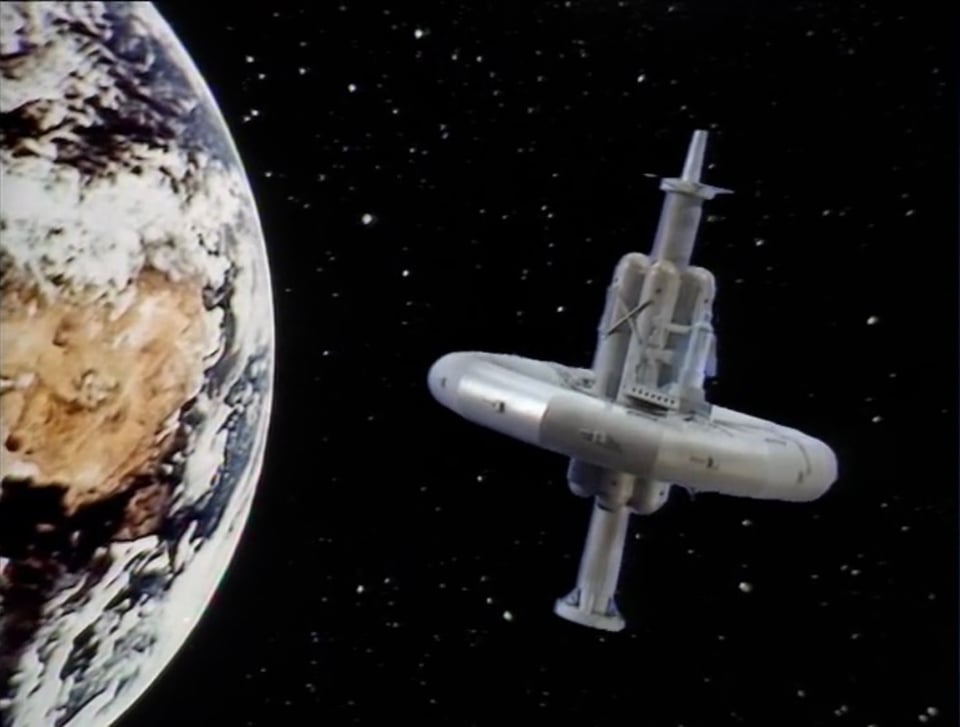

I tell you what isn’t brilliant, though. The opening model shot of The Ark in Space. It seemed to me to be quite shockingly bad. The way Nerva Beacon wobbled next to that photograph of the Earth, which just looks much less three dimensional, much more photograph-y, than that at the start of Spearhead from Space. The flat plastic greyness of the station. The way the shuttle sitting on it has a slightly different flat plastic greyness, which means you know it’s going to take off at some point, even though you’re ten and don’t really think about such things - and for some reason my suspension of disbelief just failed.

I don’t like or plan to be negative in these pieces. Or much at all really. But this is an honest account of what happened that day in 1989. For the rest of the story all I saw was white sets and worried actors. Which is weird, because those same sets convinced - and convince - me in Revenge of the Cybermen in a way they didn’t here. Which just set my brain off wondering why Nerva looks so much worse in this story than in that one. Which I thought (and think) it does.2

Maybe I was unconsciously comparing the video to the thrillingly horrible Target novelisation. But I don’t think so. I have no memory of doing that, and the memories of the disappointment of The Ark in Space are strong. But I repeat, I don’t strive to be a controversialist. I take no pleasure in not enjoying something so widely enjoyed. I’m disagreeing with consensus, not saying that the consensus is wrong.

It’s fair to say that the all conquering The Ark in Space was the first Doctor Who story that ever disappointed me, and there have been very few since that have done so. It wasn’t just the age of the material. I’d liked The Daleks the week before. I loved The Time Warrior which I saw the week after.

I found Noah impossible to care about, despite the horror he’s going through. His lifting his green bubble wrap covered hand has, to me, the kind of kitsch grandeur associated with something like Ranquin praying to a tentacle in a pipe in The Power of Kroll (1978) or any number of Doctor Who’s more notable production failures.

I don’t like the scene where the Doctor bullies Sarah Jane into succeeding (“Oh, Doctor. Is that all you can say for yourself? Stupid, foolish girl. We should never have relied on you. I knew you'd let us down. That's the trouble with girls like you. You think you're tough, but when you're really up against it, you've no guts at all. Hundreds of lives at stake and you lie there, blubbing!”) - and it’s made worse, not better by his patronising explanation “Don't be ungrateful. I was only encouraging you.”

Yes, it’s arguably necessary in the context of the scene, but the scene itself is only there, like anything is, by authorial fiat. Simply don’t have Sarah get stuck in the first place. It’s not as if it’s dramatic when she does. Then you don’t have to have the Doctor being - as Sarah rightly calls him - “a brute” in a way that does nothing good or interesting with this newly minted incarnation’s character, and which seems far worse to me than much much criticised scenes in Joy to the World (2024).

There’s just something about the high seriousness3 of The Ark in Space, and the way that combines with its production, that I find unpersuasive; and the performances from basically everyone apart from the regulars don’t help. It bounced off me. To me it feels written and made in a rush. (Which we know it was, although I didn’t know this then.) This is something that fandom has a whole has never thought of it as being. It’s like Nightmare of Eden (1979). But Nightmare of Eden is more fun. And has a better script. And marginally more convincing monsters.

I could go on. But chances are, you’d prefer me not to, right? But at least you know I’m being honest when I praise something. I ain’t doing it for clout. Not even the one from The Leisure Hive (1980).4

The Ark in Space remains hugely popular into the new century. It was one of the first Doctor Who stories to be released on DVD, as well as on VHS, it was later re-released as a Special Edition DVD, with more special features and further improved picture quality. No less a figure than Russell T Davies would call The Ark in Space his favourite ever Doctor Who story when interviewed at the British Film Institute, and went so far to include it in a “virtual season” of television and film he programmed for the Guardian newspaper.

His successor Steven Moffat too would cite the story as a personal favourite, writing the introduction for the 2012 reprint of the novelisation. Chris Chibnall’s views on the story are unknown to me. But they’re not going to be mine, are they?

The Ark in Space is one of the most successful and important Doctor Who stories ever made - and it really doesn’t matter which criteria you use to judge that. There’s actually something quite pleasing about being quite so irrelevant on all this. After all, it doesn’t really matter if this story is just not something that I ever want to see. It’s genuinely not something I’ve ever re-watched simply for pleasure. Not once. I’ve only seen it when a new physical medium of it has been issued. Or when honour requires it, such as when writing something like this.

It’s whirring away in the background now for the second time today. In Part Two, I genuinely feel some queasiness where I once just saw bubble wrap and boggled. I do like the implication that humanity is itself just another kind of plague. I can see an attempt to suggest an emotionally damaged society rather than just obviously inexpressive acting. I’m still not sure why Vira is being played like that, but at least her smile in the final shot indicates a purpose behind it.

The Wirrn still look a bit too much like dog turds on sticks for my brain to interpret them as any sort of threat, but Doctor Who monsters have looked a hell of a lot worse. Noah’s sacrifice is not exactly moving. But I don’t find it silly, in a way I did as a child. Middle age doesn’t coarsen you. Middle age makes you soft. If I’m honest, and I strive to be, I’ve never enjoyed it more. But that’s still not very much.

I still don’t think it’s even the best Doctor Who story set on Nerva Beacon, but maybe I’m finally getting into sync with The Ark in Space? Maybe it’s just grown on me. Or maybe in me. It woke me up too early is all. It’s been gestating all this time. Perhaps soon it will be ready to take control.

Smyth’s was the case that caused the resignation of the most recent Archbishop of Canterbury. ↩

They’re on video, not film, right? You can see little hints of the blue of the CSO backdrop on the grey model. It adds to the air of plastic unreality. ↩

“There was not much ‘joke’ in the last days” says the Ark’s “First Med Tech” Visa at one point, and with the exception of The Doctor’s admittedly brilliant claim that Surgeon Lieutenant Harry Sullivan is “only qualified to work on sailors” I don’t recall a single funny line, even from my most recent rewatch. ↩

“You mentioned Fomasi?” ↩