1990

“It’s all just a little bit of history repeatin’.”

“1990 was the brainchild of Wilfred Greatorex, and conceived as literally ‘1984 plus six’; a series that would show what the UK would be like a dozen years hence once, as he expected, individual liberty was forcibly suppressed in Britain in favour of the common good by anti-freedom organisations, such as trades unions…”

Ha. No. Even I can’t keep that conceit up for much more than a dozen words or so. I don’t want to write about the 1977 TV series “1990”. Not least because so much of Greatorex’s work makes me bilious. Although looking at the 1990 that was, rather than a dystopia fantasised about by a writer I don’t really like, is not much cheerier, at least in Doctor Who terms.

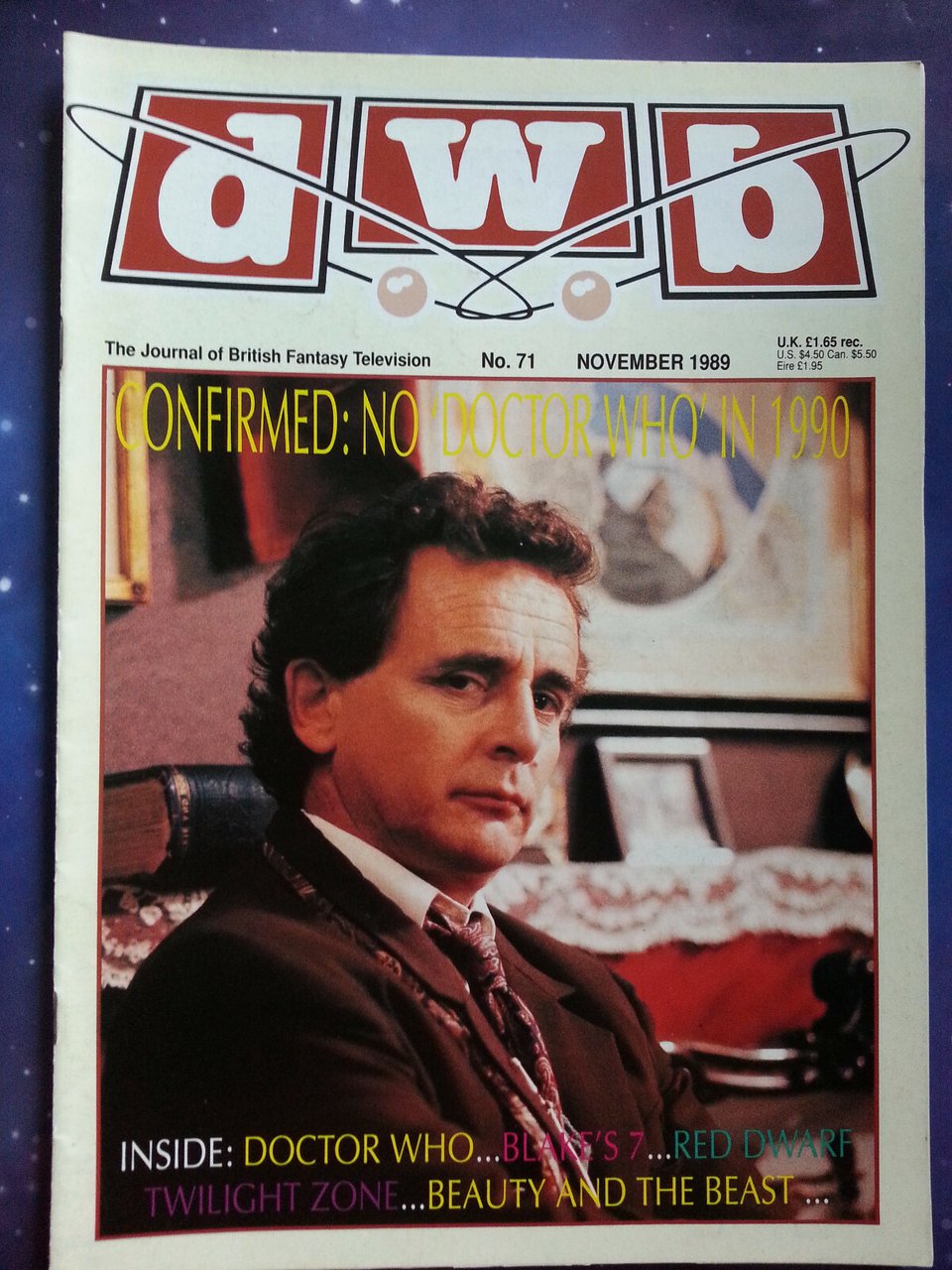

But that is where we are in The Long Way Round section of this newsletter, in which I in theory write about every old money Doctor Who story in the order in which I saw them. In 1990, for the first time, this involves no new stories, only new-to-me stories. Because 1990 was the year that never was. The first year since 1962 in which no new Doctor Who was transmitted on British television. We sort of knew that going in. The scabrous fanzine dwb had run “Confirmed no Doctor Who in 1990” on the cover of their November 1989 issue and while dwb was often wrong, here their logic was sound, and even a teenager with a shaky, nascent grasp of the television production of the period could understand that they needed to start making the series in March at the latest if it was going to be back on TV before next Christmas.

But knowledge is not experience or understanding, and the feeling, the hope, was that 1990 would be a kind of gap year. One in which we’d find out what happened next, not the first of 14 such years, split nearly evenly into runs of six and eight. “It's not the despair... I can take the despair. It's the hope I can't stand.” says John Cleese in Clockwise, a film made in 1986 and first shown on the BBC on Christmas Day 1989. He wasn’t talking about being a Doctor Who fan. But he might as well have been.

Yes, in 1990 the BBC Videos were dramatically upping their release rate to compensate for the absence of a show. Giving us access to old stories we’d dreamt of seeing but never imagined we actually would. But then, as now, merchandise (and narrative merchandise is still merchandise, no matter how brilliant it is artistically) isn’t really a substitute for a new and ongoing television series. A television series is innately out in the world in the way that the Doctor Who Magazine comic strip and VHSes of black and white stories just aren’t.

There were Target Books books, of course. But they were petering out too. The New Adventures were just a twinkle in Peter Darvill-Evans’ eye. And again, merchandise. Not the sort of thing anyone might just turn the TV on and see. The sort of thing you’d need to actively seek out and then cash out for. As the year dragged on we had to face up to an alarming possibility never quite considered by fandom. That Doctor Who might have already come to an end. That then was as inconceivable as Coronation Street or EastEnders ending is now. As inconceivable as Crossroads ending had been a couple of years before. But like the last of those three, it had already happened.

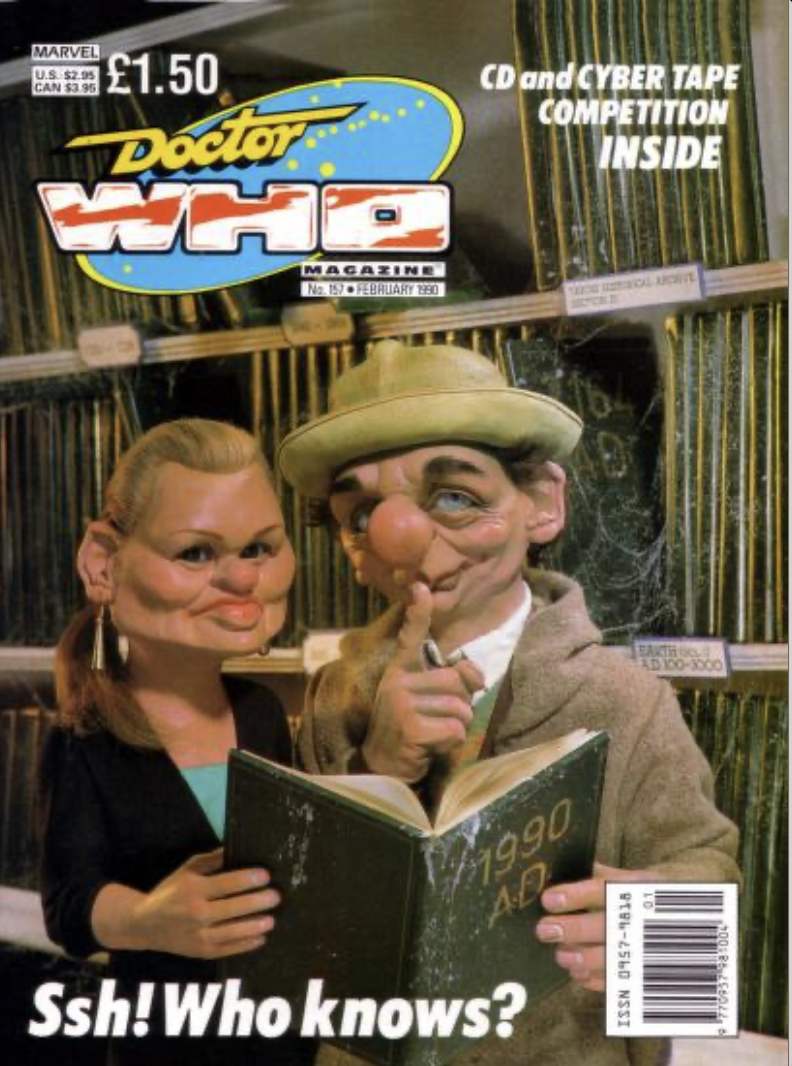

Almost all of a decade later, I’d write my first article for Doctor Who Magazine. A short piece about 1990 for the magazine’s own twentieth anniversary special, in which twenty fan writers tackled a year from the Mag’s own history each. It was an interesting conceit, not least because DWM had at this point spent roughly half of its existence as a TV tie-in magazine tie-ing in to a TV series that was no longer being made. Which is insane, and also a remarkable tribute to the people who edited DWM, particularly in the years after 1990, who turned it into a magazine that included serious archive research and did so much to set the tone for later stages of Doctor Who fandom’s own life.

I’m going to, as I’ve done a few times in the past with other bits of my own archive, repeat the whole of that article below before commenting on it. I’ve not edited or changed it. I’ve not even had to copy edit it. One of the advantages of having been writing about Doctor Who for so long, and it being out there and having been read and being available, is that there’s little room for self-deceit on these things. I can’t pretend I didn’t give a good review to The Ghosts of N-Space Episode One in a fanzine in 1996.1 This is what I said when Doctor Who had been a decade dead and I for one never expected it to return as a mainstream television series again.

Endings matter. Endings give meaning. The final episode of a TV series is important. Done right, it offers more than basic closure and answers to long-asked questions. A good ending gives a programme its final shape, can even make it seem as if the series was inevitably heading this way all along. The most impressive examples, such as those afforded to Doctor Who’s spiritual sibling Blake's 7 or sitcoms like Only Fools and Horses, actually provide the filter through which the public still perceive the now-dead series; enshrine exactly how it will be remembered by the mass audience. Living, if you like, is in the way we die.

Doctor Who doesn’t have an ending. It just stops. There’s no scene where troops wipe out the regular cast, no liberation for the prisoners of Colditz, no surprise windfall of millions of pounds.

Nothing.

Without resorting to TS Eliot’s beautiful cliché concerning bangs and whimpers, we all know the series didn’t die well. Survival is a good story, but it isn’t an ending, simply an end. It’s an instalment, not a final bow. Even with its tacked-on soliloquy and walk-into-the-horizon, as a finale it lacks everything.

The end of Doctor Who isn’t expected or planned. Worse, it isn’t even admitted to. There’s no announcement; just a lack of programme neatly smoothed over by the promise that normal service will be eventually resumed.

Flashback: I’m 11, 12 and 13 years old (this is how long it takes). It’s a short walk from where I get off the school bus to the newsagent where I pick up my DWM. A short walk, but one that seems long and loaded with expectation. I’m 11 or 12 or 13 years old. I know nothing of publisher’s lead times or magazine deadlines and every month for well over a year, I enter the shop hoping, maybe believing, that I’ll open my logo-adorned purchase and the news will be there.

It never is. Eventually I realise that it never will be. It’s a gnawing, protracted, slow-dawning realisation, a long and unpleasant process. “It’s not been cancelled,” I tell people. I’m missing the point. In order to stop a programme you don’t have to ‘cancel’ it (whatever that actually means) you just have to not make it.

There was a moment when ‘Doctor Who returning’ became ‘Doctor Who coming back’. It’s a small distinction, but an important one. Although it only became irrevocable later, effectively in December 1989, Doctor Who the weekly television series that had run for 26 years, one week and six days, finished. We know that now, though we didn’t know it then. The series ended. What’s past is past. What’s future, whatever form it takes, is resurrection, not continuation. The term ‘Season 27’, so often bounded around in the first quarter of the 1990s, no longer has any meaning.

Endings matter, even when they’re not really there.

And we’re back in the room.

Ignoring the obvious fact that I’ve not developed at all as a writer since I was 19, clearly the most important thing I got wrong was that I could never have imagined anyone would be so stupid as to undo the 1996 Only Fools and Horses finale.

But more on-topic, I fundamentally failed to predict not only Doctor Who being revived, but it being revived by essentially the only person whose approach guaranteed the series would, on its return, be both a revival and continuation, one bound to and not embarrassed by its past self, in dialogue with it even when it didn’t acknowledge it. Which is to say, I failed to predict individual genius, and I’m okay with that - not least because the whole revival of Doctor Who we actually lived though seems like something that would happen under the influence of Black Mercy, rather than an event from real life.2

I unconciously wrote “lived through” there. Not “are living through”. I didn’t deliberate use the past tense. It just happened. Which brings me to the other difficulty I have writing about 1990 right now. It’s not that the situation is the same now as then. It isn’t. This is not the year that never was. We’ve had a whole, brilliant, series of Doctor Who this year, and a wholly brilliant Christmas special a week before the year began. But it all already seems so long ago. It was less than five months. Gone, as a wise man once wrote, like breath on a mirror.

No, this is not 1990 again. But there are uncomfortable parallels, chiefly that we’re living in a liminal space. We’re told - and I have no reason to doubt - that the series’ future, and the specific form it takes and the specific point at which it returns, depends in part on the reception of upcoming spin-off The War Between The Land and the Sea, and in any case cannot be taken until after it even if it doesn’t. “The TARDIS is not going anywhere” is the standard quote being rolled out by BBC bigwigs when people question if and when Doctor Who will come back. Which if nothing else, is an appropriate thing to say while we all wait for a spin off from Doctor Who And The Silurians. But it’s a bit too close to all those bromides from the early Major government for comfort. At least if you’re a fan of a certain age. If you are, like me, someone who never grew out of Doctor Who, because it was taken away before I had the chance.3

I claim no knowledge of anything other than publicly available material. Literally everything I say about now, rather than then, may be wildly, laughably wrong. But I can’t help but feel that the crucial difference between 1990 and now is that now the BBC wants to make Doctor Who. That it is circumstances, fundamentally, that have taken the programme away from us and indeed from them. Whereas the last time we were in this position, BBC Drama was rebuffing, ignoring and ghosting approaches from the co-producers it was also publicly saying it would encourage. To the extent that in 1992 BBC Head of Drama Peter Cregeen wrote to Philip Segal, later the producer of the 1996 Doctor Who TVM, to explain that his proposals were not being looked at in any depth because the BBC still thought it “premature” to bring back Doctor Who and could he please just leave him alone for a minute to concentrate on important things like Trainer, thank you very much and bye.

The impression one gets now is that if there was a way to throw together a Christmas special, BBC One would bite your hand off. But again, we’re rapidly approaching a point where surely they need to start making the series in short order if it’s going to be back by next Christmas and as such it feels inevitable that we are a couple of months away from the start of another year that never was.

When I was 17 I broke my left ankle. When I was 18 I broke my right. I remember, on the latter occasion, lying there in the dark, my foot in a pothole and very much at the wrong angle to my leg, and a part of my brain managing to think, between the surges of agony, “This is exactly what it felt like last time. I couldn’t remember until now.” I cannot, of course, remember exactly what it felt like on either occasion anymore, and it’s not the passage of thirty years that has done this. There are feelings your brain won’t permit you to remember unless you’re re-experiencing them anyway.

And I’m remembering one of them now.