Can you really remember more than a single sentence?

We're all tired, we've never been more distracted, and our memories are famously unreliable. It's a miracle we retain anything at all.

You've just read something that has left you slack-jawed.

It might have been a news story that transformed your understanding of a political issue; it might have been a long-form feature that completely flipped your perspective on a conflict; it might have been an interview that made you suspect that your favourite musician is actually a bit of a dick.

And then you try to explain it to somebody else. As you talk, you struggle to recall the salient statistics, convincing lines of argument, or even the names of people and places relevant to the topic at hand. What sounded so convincing on the page is sapped of any persuasive power, like a barrister bleeding out during closing arguments.

Why is this? My theory, essentially, is that most adults can't retain much more than one sentence about anything.

You might think I'm exaggerating for effect (I'm not) or that I just have a particularly bad memory (I might), but in the course of writing this piece, I've found that at least some research backs up my hare-brained idea.

So, let me elaborate. And maybe see what you can remember at the end.

Forget-me-nots

Let's start by looking at a topic that each of us is deeply familiar with: our own lives. I think the single-sentence argument applies here, too, and that we tend to boil our personal histories down into chapters that can be summarised in just a few words.

So, if someone asks you what you were like as a child, you might try to wade through your soupy early memories in an effort to explain your character. But it's much more likely that you'll fall back on some sort of family lore and give an answer that makes use of oft-repeated anecdotes in order to draw a straight line between the kid you were and the adult you are now (“Oh, I’ve always been competitive,” you say, not really thinking about it at all, before launching into a story about an event you don’t really remember but seems like the sort of thing a competitive child might do).

If this is the kind of mental shortcut we turn to when recounting our own lives, how much complexity can we really expect to retain when handling an entirely new topic? This is true even when the information being communicated to us is of vital importance - such as when receiving a medical diagnosis.

Researchers in the field of health literacy work to understand how healthcare information is communicated, received, and understood. Their findings make for sobering reading:

"40-80% of medical information provided by healthcare practitioners is forgotten immediately. The greater the amount of information presented, the lower the proportion correctly recalled; furthermore, almost half of the information that is remembered is incorrect."1

If a doctor can expect their patients to immediately purge 80% of what they’ve just been told in a face-to-face interaction, what the hell kind of percentage can writers and editors hope for?

Precious memories

I don't doubt for a moment that there are areas in your life that this rule would not apply to. But these tend to be the things that you have engaged with or studied for years - often the subject you studied at university or the field you dedicated a career to. By returning to the same topics over and over again, we're able to draw on the power of our long-term memories. Long-term memory enables you to form stable, complex, nuance-filled mental models of a subject. Then, when you learn something new about this subject, you can fold it into your long-term memory like a lovely, airy cake batter.

Short-term memory, by comparison, is quite shit.2

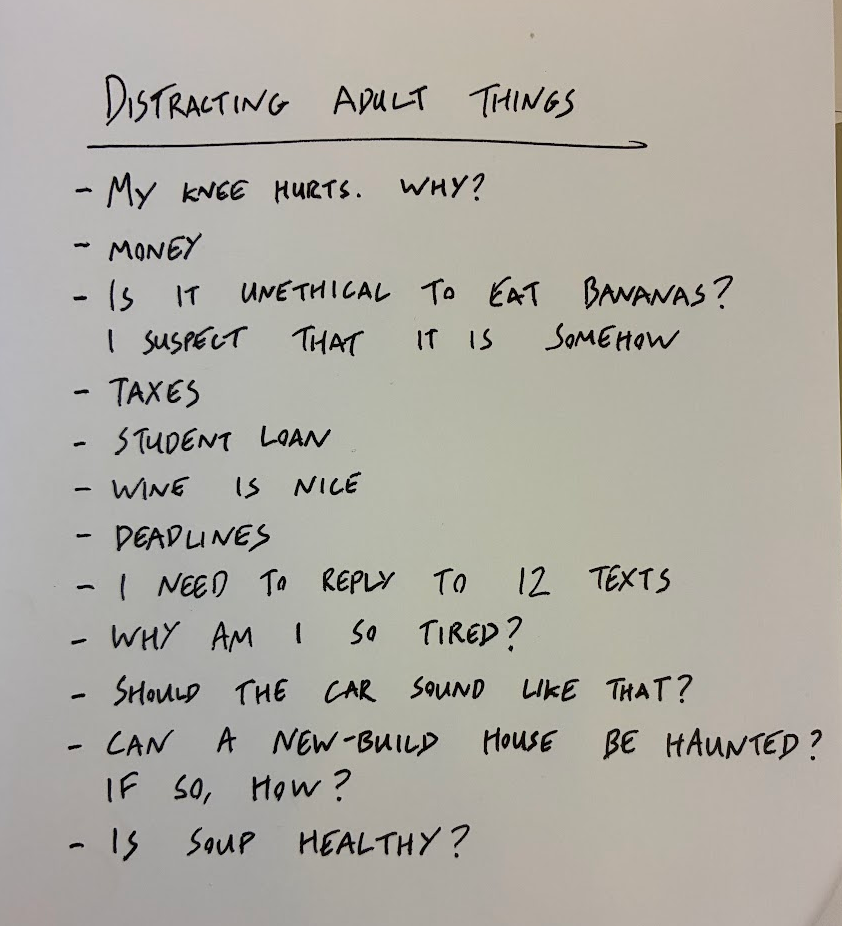

When you can only rely on your short-term memory (because you're learning about an unfamiliar subject, because you're being bombarded with new information, or because you're being distracted by the 101 distracting adult things you need to think about today) your ability to retain information is dramatically limited and easily impaired further. This, fundamentally, is why I think it's reasonable to expect adults to only ever remember a one-sentence summary of whatever we've written for them.

So, if we accept that most of our readers will forget most of what we write, it begs a question: why bother writing more than a sentence at all?

Well, just because a person won't later recall everything you've said, it doesn't follow that they're credulous, gullible, or easy to convince. You still need to state your case, argue your point, and engage the reader's interest - you just can't assume that all of that context will stay with them for the long-haul.

The biggest takeaway of the single-sentence theory of readership is that you need to know exactly which single sentence you want to lodge in your reader's mind and work to make that happen. It's an argument against kitchen-sink messaging, where you throw reams of extra information into every product announcement, say, or oodles of tangential material into a feature.

And lucky for us, it’s an argument that reinforces other good working practices. When we start with our single sentence, we’re in the habit of thinking about our angle, our hook, and our headline before we get into the weeds of making our argument.

And then, with that sentence in mind, we make our argument to the best of our ability, in all of the detail and depth that we need to. The nuance, context, and statistics that support our point of view might not live long in the memory, but they’re still essential. Think of them as the seasoning: no one's going to rave about them afterwards, but people will walk away shaking their heads if they’re not there.

Kessels, R. P. C. (2003) Patients’ memory for medical information. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 96(5). ↩

Baddeley's model of working memory is one well-known attempt to explain how we marshall our attention and working memory towards the experiences we encounter. Reading about it does sort of make you wonder how we ever remember anything. ↩

You just read issue #3 of boxouts. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.