The Chicago Bulls, Irish sexagenarians, and approachable writing

Will a reference to Irish sixty-somethings in the title of this edition play nice with spam filters? Let's find out together.

There's one debate that I’ve found myself having pretty often when managing teams of writers.

It would typically begin when I asked a writer to simplify something they'd written - to strip out jargon, to spell out an abbreviation, or add an explanatory sentence somewhere.

“Everybody knows that term”, the writer might say, “and that abbreviation is actually really common”. They might argue that the publication’s audience doesn’t need any extra explanation - the readership has been following this developing story for weeks.

It sometimes felt as though I was touching a sore spot. I sensed that some writers felt I was asking them to sacrifice depth or dumb down their writing. So, I decided to take some time to clarify to myself why I was asking for these changes and whether it was really important.

The conclusion I reached is that it does matter, and is even worth the occasional debate about. And I think the very fact that the issue seems to ruffle feathers hints at an underlying set of assumptions that we don't often talk or think about as writers and editors.

The deep end

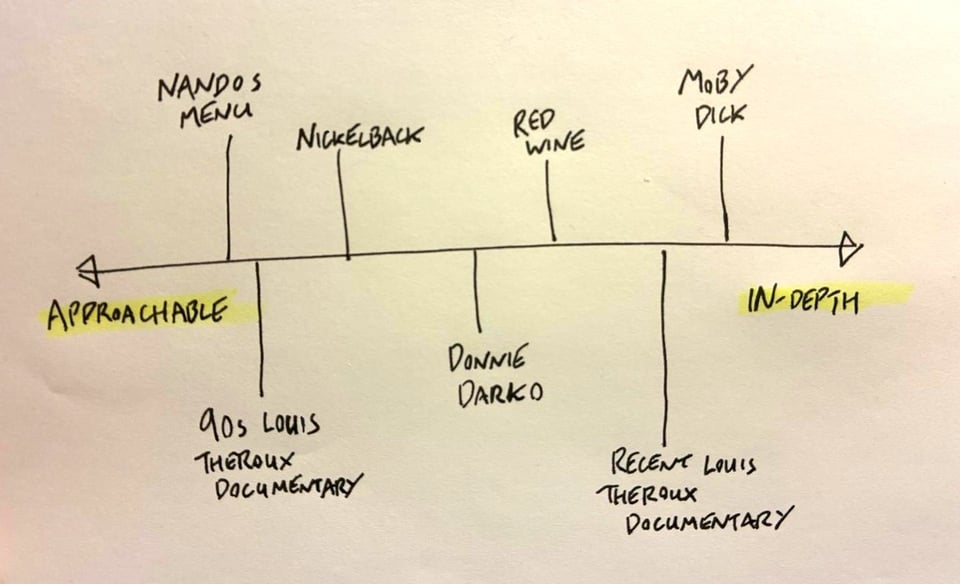

I think a lot of people imagine a straight line with 'in-depth' at one end and 'approachable' at the other. On one end, they put publications like the Financial Times or the London Review of Books. On the other, they put The Sun and The Beano.

There's usually a hidden value judgment there, one that imagines difficulty as a signifier of importance and cultural worth (after all, watching a Shakespeare play is a bit difficult. Reading Joyce is a bit difficult. Reading Theodor Adorno is a bit bloody difficult). The tacit implication here is that depth, profundity, and un-approachability all occupy similar territory - they’re not quite interchangeable but they all at least share a postcode. Approachable pieces of writing, meanwhile, are a bit less worthy, a bit less important.

This mental map ignores the skill that goes into taking a complex story and delivering it in a way that anyone can engage with. This is what great journalists do in their reporting - they take dry economic policy, niche subcultures, or conflicts with deep historical roots and tell you what's happening (and why it matters) in words that you can understand.

Hoop dreams

Perhaps the most vivid example of this playing out for me was when I got a phone call from my mother about Michael Jordan.

She'd been watching The Last Dance, the documentary series that revolves around Jordan's final season with the Chicago Bulls. And despite the fact that she has never watched a game of basketball in her life, she wanted to talk to me about the heyday of the Bulls.

In other words, The Last Dance is so approachable that you can love it even if:

you've never heard of Michael Jordan

you've never heard of the Chicago Bulls

you're an Irish woman in your late sixties and you've literally never touched a basketball

And at the same time, The Last Dance is also suuuuper in-depth. The programme-makers interview dozens of Bulls players, coaching staff, and commentators across ten episodes. All that might imply some kind of career-spanning overview, but the defined focus keeps you grounded in a single year of play. Whether you’re a sports fan or not, you understand the stakes and connect with the drama.

And crucially, the programme's makers were able to remove barriers to understanding in a way that enabled viewers like my mum to connect with the human stories at the show's heart. They were able to give you a sense of Jordan’s personality, contextualise the significance of his achievements, and offer a window into the environment that he was operating in. And they were able to do it in a way that never felt patronising, lightweight, or dumbed down.

In-depth and approachable aren’t on opposite ends of a spectrum after all. They’re separate things, and there’s no reason you can’t produce a piece of writing that bears the hallmarks of both.

Boiling it down

So, my basic position is that it’s possible to tell deep, engaging stories in ways that are accessible to very large numbers of people.

Achieving this goal isn’t always easy, but I reject the argument that this approach necessarily represents a ‘dumbing down’ of a given piece of work. Okay, you might be dumbing down if you choose to patronise your readers or remove important substance, so just don’t do that. Instead, consider the notion that a big part of our job is artfully removing barriers to understanding.

You might say that this is all well and good, but it doesn’t really apply to your audience. Your audience already understands all your jargon and abbreviations, you say. But do they really? All of them? And would they be offended by a piece of writing that finds other ways - clearer ways - to say the same thing?

This is particularly important if you're at all concerned with reaching more people over time. If you're a copywriter for a brand, you might have excellent reasons to believe that your audience knows your specialist terminology inside-and-out. But don't you want to sell to newcomers, too? Don't you want your existing audience to be able to share your work, your messages, your stories?

The carve-outs

Perhaps you still consider you and your audience to be an exception to this rule. If so, I think you are arguing either:

a) that it is impossible to remove barriers to understanding from your work.

b) that it would be undesirable to remove barriers to understanding from your work.

Unless you’re operating at the forefront of theoretical physics or something, argument A does not apply. And even then, the TV career of Brian Cox (the boyish physicist, not the frightening actor) suggests that an attempt could be made.

Meanwhile I suspect that a significant proportion of those making argument B would be doing so on the basis of terms like credibility or authenticity - that the only way to communicate with a given audience is to do so in specific language that has the (perhaps unfortunate) effect of excluding outsiders. Linguists call this in-group language.

Whether or not this justification for un-approachability applies to your work is ultimately up to you. Either way, it’s important to arrive at this conclusion having given it deliberate thought.

After all, as much as there is a pragmatic case to be made for defaulting to approachability (more readers, more impressions, more conversions), there’s a kind of moral argument to be made for this way of working, too. Because ultimately, we probably shouldn’t be in the habit of excluding people unless we have a really good reason.

You just read issue #1 of boxouts. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.