The Proverbial Memory Lane

I wrote for the Hedgehog Review about Alexander Herzen, the central figure of Tom Stoppard’s sprawling and marvelous trilogy The Coast of Utopia — and then I wrote another post reflecting on the same themes but from a specifically Christian point of view.

I also reflected a bit on the rise of newsletter-based journalism — a cool phenomenon in some ways but worrisome in others.

In 1975, just graduated from high school at age sixteen — yeah, a little ahead of schedule, it could happen in those days — I got my first job, working at a brand-new bookstore (B. Dalton Bookseller) in a brand-new mall, Century Plaza in Birmingham, Alabama.

I tell the story of how that job began here. I worked at B. Dalton for five years, and everything about the experience proved essential to my education, far more than any classes I took in college. (Not least the opportunity to eat Chick-fil-a for the first time, which I did almost every day for a … let’s just say a “while.”) My chief job was receiving clerk, which meant that I handled almost all the books that came into the store — an education in itself. But equally important to my formation was the place right next to the bookstore: a gloriously expansive record store called Wide World of Music.

Every day when I had a break I’d trot over to the record store to see what was happening, and I remember more than once being stopped in my tracks by what I heard — nearly knocked off my feet in one case: “Safe European Home.” But there were many other moments in that store I still remember: Neil Young’s “Cortez the Killer” — harrowing — and some unknown dude calling himself by the ridiculous name Elvis Costello, singing “Welcome to the Working Week.” They played that one every Monday morning for a while.

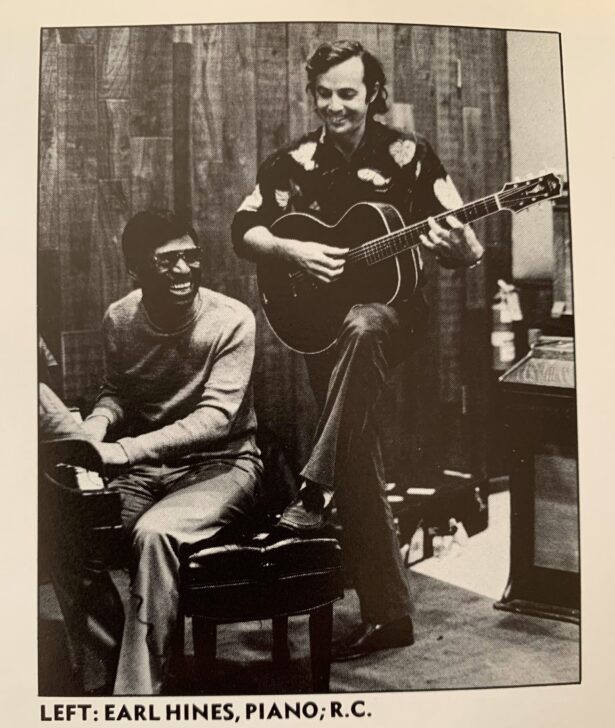

Those records all became famous, but there was one oddball recording that I encountered there that I still listen to today — forty-two years after its release. It’s Ry Cooder’s album Jazz. The point of the title is twofold: first, that not much of what you hear on the record is what anyone today would think of as “jazz”; and second, that such a development wasn’t inevitable. Cooder explains in his liner notes that his record is an imagined alternate history of jazz, a musical world that might have been. And he reaches back into that past in a concrete and immediate way, by recruiting one of the greatest of jazz pianists, Earl “Fatha” Hines, former bandmate of Louis Armstrong, to play on one song.

He also features lovely arrangements, in what he calls a “salon-jazz” style, of three piano pieces by Bix Beiderbecke: “Davenport Blues,” “Flashes” and “In a Mist.” Cooder in his liner notes — which are fascinating — refers to “Bix’s strange music”; I wouldn’t call it strange, but it is memorably atmospheric, and Cooder’s arrangements beautifully bring out its moods. I recommend that you listen to them, and as you do, meditate on the loss of one of the great geniuses of American music, dead from what was essentially alcohol poisoning before he turned 30.

If you want to get a hint of how great Bix was, just listen to “Singin’ the Blues” from 1927, with Frankie Trumbauer’s band. Trumbauer is a fine saxophonist, but … well, as I said, Bix was a genius. When I remember Bix, I always think of Armstrong’s unmatchably eloquent and terse summation: “Lots of cats try to sound like Bix. Ain’t none of them sound like him yet.”

I often think of writing a memoir about those years of my life, growing up in Birmingham during the outworking of the Civil Rights movement: reading Faulkner and Latin American literature for the first time; arguing about music and politics at Charlemagne Record Exchange; gathering around a friend’s TV to pass joints and watch Muhammed Ali fight Earnie Shavers; watching baseball at Rickwood Field; meeting a Birmingham native, then living in Manhattan, who on a visit home had brought single-malt scotches to educate our palates … and all as that gritty city, the epicenter of violence and cruelty against black Americans was figuring out how to live as an integrated place. It was a heady time. If I ever do write that memoir, I already have a title: Wide World.