Texas Bookends

Modern life is a peculiar thing. Last week Teri and I, in a risk-taking mood, made the 80-minute drive to the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, where we saw their special exhibition Flesh and Blood. Maybe not noteworthy if you live in London or Paris or Manhattan, but it’s rather strange to live in Waco and be less than an hour-and-a-half from the opportunity to see paintings by Raphael and Caravaggio — plus Michelangelo, Fra Angelico, Manet, Picasso, and other luminaries in the permanent collection.

Then of course we did what all visitors to Fort Worth must do: we went to Joe T. Garcia’s for lunch. The food is solid Tex-Mex eating — not exceptional except for the fabulous lard-based flour tortillas — but the real attraction is the place, which has expanded from its original 16 indoor seats to a vast outdoor garden that seats 1500 people and features several fountains, over a hundred trees of various descriptions, and just short of a thousand potted plants. It’s so much fun. Here’s a drone-eye view.

And, as I had promised, when we were there I lifted my margarita to the sky in memoriam, and in gratitude for the life and ministry of, Jim Packer.

Our grand day out. We wore our masks and washed our hands repeatedly, but none of that spoiled the experience. We may risk another venture soon.

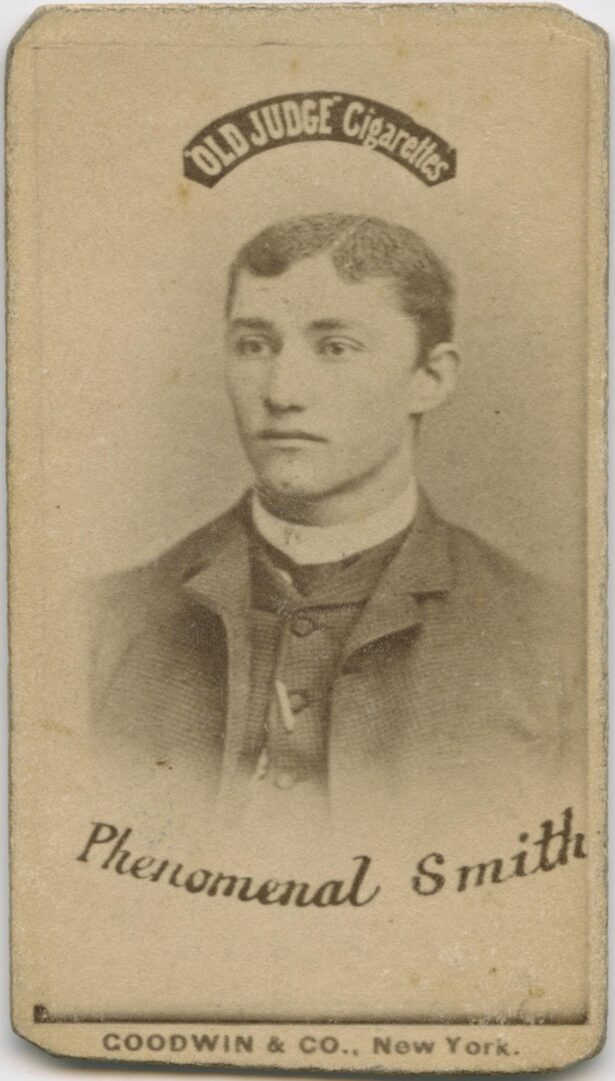

Gonna tell you all the story of a man named ... Phenomenal.

A tuatara is a lizard ... Well, it looks like a lizard, but it’s a different kind of reptile. Or maybe it’s not a reptile? It’s ... its own thing. Also, tuataras can live more than a hundred years, hold their breath for more than an hour, and see with a top-of-the-head third eye.

A lovely essay about Dungeness, where England sinks into the sea.

A passage from Larry McMurtry’s 1968 book of essays on Texas, In a Narrow Grave:

As I was driving through an oil-town called Electra I passed a senior citizens’ home and saw an old man in a red mackinaw sitting in a wheelchair on the south side of the building, in the lee of the wind. His name was Jesse Brewer, and since he had been my first friend in the world, I swerved off the road and stopped. During the war, when most of the younger men were gone, Jesse had cowboyed for my father for a while. I have always suspected that his real job was to keep me out of danger, or at least out of the way.

When I walked up and said hello he was chewing tobacco and looking out across the brown rolling country to the southwest. “How you doin’, Larry?” he said, no whit surprised to see me. Then, looking cautiously around to see who might be watching, he spat tobacco juice on the roots of a domesticated prickly pear that was growing by the wall. The look around was a habit formed in ranch houses, where women were apt to take unkindly to men who chewed.

Jesse was in his nineties, and had sunk a little farther into his Mackinaw in the five years since I had last seen him. His spirits, however, were excellent. He at once proceeded to ask me all the questions that are standard in the cattle country. How were my father’s cattle? Was there any grass? Where was I living?

When I told him Houston he made a grimace of commiseration. “Hard to breathe down there, ain’t it?” he said, convinced, as most plainsmen are, that any place south of Waco must be a malarial swamp.

As we were chatting, a nurse came out, decreed he had had enough sun, and briskly wheeled him in for a morning of television. For a man who had followed the cow, it seemed a dull end. We waved and I drove on, and did not see Jesse alive again.