Silence, Minuets, Gold

A pocket medicine chest, with the Rod of Asclepius on its cover; copied from an original found at Pompeii.

I’m still blogging about Babylon, among other things.

David Bordwell, in The Way Hollywood Tells It:

Far from being a noisy free-for-all, moreover, the industry’s ideal action movie is as formally strict as a minuet. Many principles of unity have been laid out with remarkable precision in a manual by screenwriter William Martell. Martell shows how strategies of contemporary script construction — act structure, ticking clocks, the “broken” hero — are worked out in the genre. He claims that the most important element of the action film is the villain’s plan, and he insists that it be well motivated. He points out that in the first half the hero is likely to be reactive, whereas in the second half the hero seizes the initiative. Critics tend to praise films in which the hero somehow mirrors the villain, but Martell shows that this is a genre convention. He also categorizes various sorts of hero (Superman/Everyman) and outlines variants on the buddy-cop and fighting-team format, even pinpointing the exact moments when conflicts surface. Throughout, Martell refers to exemplars, most frequently Die Hard, “the model of what a genre script should strive for, and the barometer with which to measure all future action films.” Ironically, the genre considered most scattershot turns out to have the most widely recognized formulas of organization.

Dorothy Sayers, letter of 7 October 1941:

I haven’t got a pastoral mind or a passion to convert people; but I hate having my intellect outraged by imbecile ignorance and by the monstrous distortions of fact which the average heathen accepts as being “Christianity” (and from which he most naturally revolts). And it does seem to me that, in the present state of confusion, the mere assimilation of the basic dogma would offer sufficient exercise for the mental teeth and stomachs of people; and further, that it would be helpful if writers and speakers and broadcasters would concentrate on those facts, and if they were able to say: “It doesn’t matter where you go – ask the Pope, ask the Patriarch, ask the Archbishop of Canterbury, ask the Moderator of the Free Church Council – they will all say the same thing about this bunch of dogma.” (I admit the obvious diplomatic difficulty of extracting anything definite from Cosmo Cantuar [Cosmo Lang, then Archbishop of Canterbury], or of coaxing the Pope and Patriarch onto one platform – but there! the Barren Leafy Tree’s very reasonable excuse that “this was not the time for figs” was held to be unacceptable, and there do seem to be moments when one must perform the impossible or perish!)

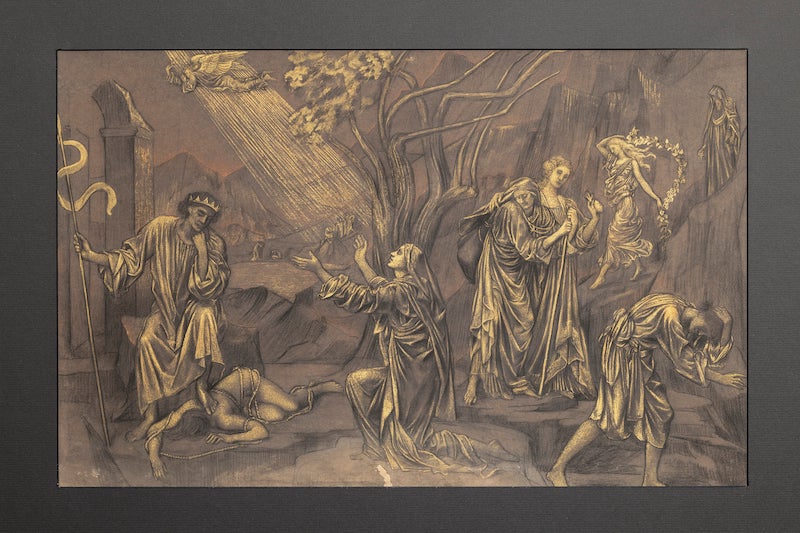

Evelyn de Morgan, The Gold Drawings

Patrick Leigh Fermor, A Time to Keep Silence, during a visit to a monastery:

These men really lived as if each day were their last, at peace with the world, shriven, fortified by the sacraments, ready at any moment to cease upon the midnight with no pain. Death, when it came, would be the easiest of change-overs. The silence, the appearance, the complexion and the gait of ghosts they had already; the final step would be only a matter of detail. “And then,” I continued to myself, “when the golden gates swing open with an angelic fanfare, what happens then? Won't these quiet people feel lost among streets paved with beryl and sardonyx and jacinth? After so many years of retirement, they would surely prefer eternal twilight and a cypress or two....” The Abbey was now fast asleep but it seemed ridiculously early about the moment when friends in Paris (whom I suddenly and acutely missed) were still uncertain where to dine. Having finished a flask of Calvados, which I had bought in Rouen, I sat at my desk in a condition of overwhelming gloom and accidie. As I looked round the white box of my cell, I suffered what Pascal declared to be the cause of all human evils.

Pascal, in his Pensées: “All of humanity's problems stem from man's inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”