Scott Joplin

Scott Joplin was born in 1868 or thereabouts. Probably in Texarkana, probably on the Arkansas side. His father was a railway worker and for a while he was one also, though eventually he was able to begin making a career he preferred as a music teacher. Then he became a performer and a composer of songs in the form that we know as ragtime. When Joplin published “Maple Leaf Rag” in 1899 he grew relatively wealthy and was recognized as the greatest exponent of ragtime music. However, the popularity of ragtime began to wane and Joplin’s career tailed off. He died of syphilis in 1916, in a New York hospital, and was soon completely forgotten.

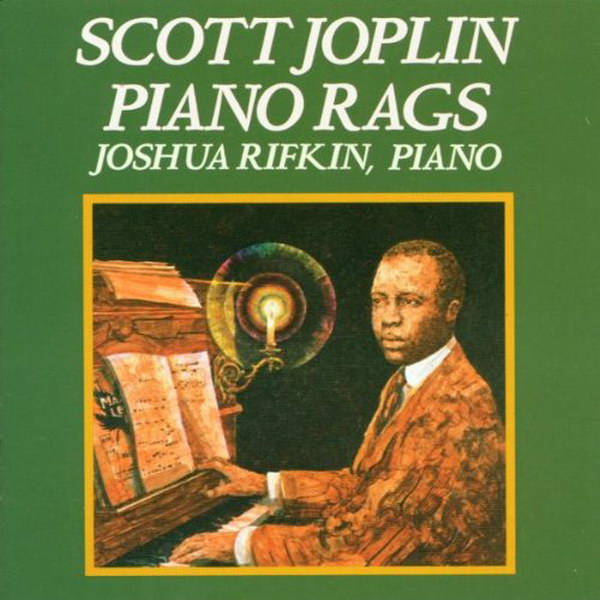

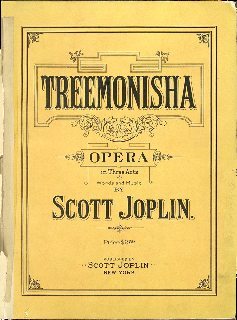

So things remained for half a century. But then, in 1970, a classical pianist named Joshua Rifkin released a record called Scott Joplin Piano Rags on the Nonesuch album label. Nonesuch was a classical label, which is fitting because Joplin thought of ragtime as a kind of classical music. Rifkin’s record was unexpectedly popular, ultimately becoming the first million selling record on Nonesuch, and it reintroduced Joplin’s music to the American public. This recovery was greatly aided by the appearance of one of Joplin’s rags, “The Entertainer,” in Marvin Hamlisch’s score for the movie The Sting. (An anachronistic choice, since the movie was set in the 1930s.) It was soon discovered that Joplin had written a great deal of music, including two operas, one of which was performed in his lifetime but was later lost. (The manuscript was confiscated after Joplin had become ill and unable to pay his debts.) The other one – a story about the importance of education in the Black community – survived, and was structurally and melodically complete, but had never been scored. Gunther Schuller orchestrated this opera, called Treemonisha, and had it performed in 1978. The resurrection of Scott Joplin as a major American composer would thus seem to be complete.

But here another character enters the scene, a man named Rick Benjamin (not Franklin, as I wrote in a draft of this newsletter that somehow got published – apologies to Mr. Benjamin). When Benjamin was a student at Julliard in the late 1970s, he discovered in a building about to be torn down thousands of musical scores that had belonged to the Victor Company – the biggest publisher of music in the early twentieth century. Benjamin was fascinated by much of this newly-recovered music and gathered a group of Juilliard students to perform some of it. A recording someone made of that performance on a cheap cassette fell into the hands of a record producer, who was quite interested. So Benjamin created the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra, which then recorded its first album. Paragon is still around and Benjamin is still leading it.

Benjamin never liked Gunther Schuller’s orchestration of Treemonisha; it was done on the scale of nineteenth century grand opera, which Benjamin believed was a form completely unknown to Joplin. Joplin’s lost opera, A Guest of Honor, appears to have been performed by the kind of pit orchestra that would have been commonplace in the theaters of Joplin’s time, and for which Joplin himself both performed and wrote: eleven or twelve musicians, not a vast modern symphony orchestra. Indeed, it’s quite unlikely that Scott Joplin as a Black man would ever have been allowed to hear a grand opera performed.

So Benjamin re-orchestrated Treemonisha for the kind of ensemble that Joplin would have known. I’ve been listening to Benjamin’s version lately, and it’s just wonderful. This of course may not be everyone’s kind of thing, but it highlights a kind of chamber music that sits at the junction of popular song, classical song, and what would later become jazz. To me, it’s a great delight.

I should add that I’m kind of a sucker for these smaller orchestrations. I am inclined to think that the rise of the big Mahleresque orchestra was a mistake. Music made by such a vast army always feels bombastic to me. I love the historically-informed-performance versions of Handel’s Messiah. I love the original version of Copland’s Appalachian Spring, scored for just thirteen players. I even love Lizst’s piano reductions of Beethoven’s symphonies – especially the ones performed by Glenn Gould. Rick Benjamin’s Treemonisha fits very much in that tradition of great effects produced on a modest scale.