Sameness and Difference

Abraham, from Dream Big, Laugh Often: And More Great Advice from the Bible, by Hanoch Piven and Shira Hecht-Koller.

Lately I’ve found a bit of a rhythm with my online writing: I am blogging less often at my big blog, though the posts are longer, and am moving quotations (along with notes on what I’m reading and listening to) to micro.blog. And when I post something to the big blog I note that fact on micro.blog. So if you subscribe to the micro.blog, you’ll get an email digest each Friday of everything I post online. Plus, of course, photos of Angus.

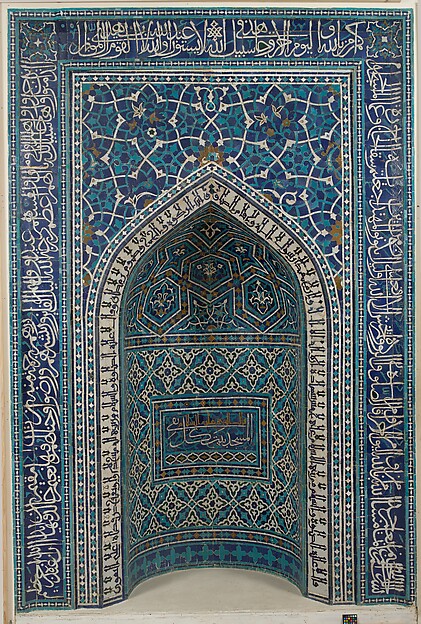

“This mihrab is decorated with patterns of flowers and vines to remind worshipers of heaven, which, in Islam, is pictured as a beautiful garden. In addition to the patterns, notice the Arabic writing. The words in curvy white calligraphy in the outer border of the mihrab are from the holy book of Islam, the Qur’an, and the navy blue writing on the pointed, white inner frame lists the Five Pillars of Islam, the most important beliefs and rules for all Muslims.”

An essay collecting a wide range of information, from a wide range of fields, indicating one overwhelming truth: Everything everywhere looks the same. “So, there you have it. The interiors of our homes, coffee shops and restaurants all look the same. The buildings where we live and work all look the same. The cars we drive, their colours and their logos all look the same. The way we look and the way we dress all looks the same. Our movies, books and video games all look the same. And the brands we buy, their adverts, identities and taglines all look the same.”

An extraordinary story about Mack McCormick, a historian of the blues who died in 2015, leaving behind an extremely confusing legacy of jaw-droppingly extensive research, elegant writing, paranoia, and possible lying. See also Ted Gioia’s response to the story, and an older reflection by him on McCormick’s legacy.

In his informal, allusive, often nostalgic Essays and Last Essays of Elia, much admired by American as well as British readers, [Charles Lamb] had described the excitement that Elia, the pseudonym he used in his essays, felt as he bought a ‘folio Beaumont and Fletcher’ – an acquisition that he had saved up for by wearing his brown suit until it was threadbare. Both scared and enraptured, Elia had dithered until 10 p.m. on a Saturday before finally setting out to walk from Islington to the bookseller’s premises in Covent Garden. When he returned home, he insisted on collating and repairing the book immediately instead of waiting until daybreak. Though Lamb treasured his books, he also made clear that most of his ‘midnight darlings’ were ‘ragged veterans’, often incomplete or imperfectly bound (he had some of them repaired by a cobbler). His collection suffered not only from his reading but from the attacks of borrowers, ‘those mutilators of collections, spoilers of the symmetry of shelves, and creators of odd volumes’. Further damage had befallen his library, as Bartlett and Welford explained, after his death in 1834. Yet they had deliberately left the books as they were: ‘no attempt,’ they declared, ‘has been made to re-clothe his “shivering folios”; they are precisely in the state in which he possessed and left them.’

Eric Ravilious, “Prospect from an Attic” (1932)