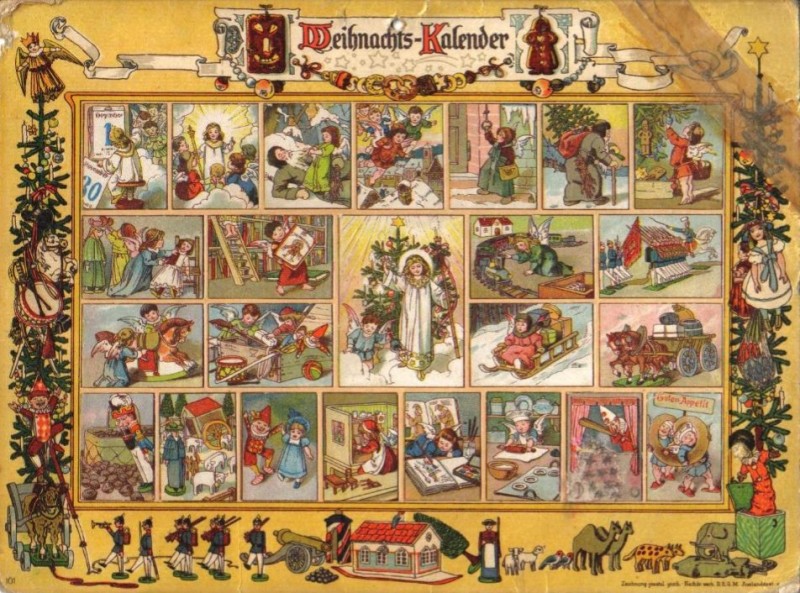

Picture-boxes in the stars

Bethlehem in Germany,

Glitter on the sloping roofs,

Breadcrumbs on the windowsills,

Candles in the Christmas trees,

Hearths with pairs of empty shoes:

Panels of Nativity

Open paper scenes where doors

Open into other scenes,

Some recounted, some foretold.

Blizzard-sprinkled flakes of gold

Gleam from small interiors,

Picture-boxes in the stars

Open up like cupboard doors

In a cabinet Jesus built.

That’s the first stanza of Gjertrud Schnackenberg’s poem “Advent Calendar”; read the whole poem here.

Speaking of Advent, listen here to my friend Ken Myers discuss the fascinating history of the hymn “Savior of the nations, come.”

When people talk about the Great American Songbook, and the heyday (nearly a century ago) of American popular songwriting, what do they mean? I can show you by taking you to the pinnacle of that art: this song, this singer, this performance.

Here is a rich and moving meditation by Matthew Lee Anderson on childlessness, family, and the Kingdom of God.

Bee Wilson: “If there was one thing Maria Montessori hated, it was play.”

Montessori believed that children were born for gran lavoro – ‘immense work’. She wrote that the ‘power of concentration shown by little children from three to four years old has no counterpart save in the annals of genius’. The purpose of education was to provide them with an environment in which they were free to work without interference from adults. This was far more satisfying for children than ‘play devoid of meaning’. When they were tired, it was because they had worked too little rather than too much. One of her principles was that ‘mental work does not exhaust; it gives nourishment, is food for our spirit.’

Who knew?

At a memorial service marking the fiftieth anniversary of Chesterton’s death, Cardinal Emmett Carter described him as one of the ‘holy lay persons’ who have exercised a prophetic role within the Church and the world. Though the cardinal was hesitant, the Chesterton Review wondered whether there might be grounds for canonisation, given the ‘special integrity and blamelessness about him, a special devotion to the good and to justice’, coupled with the ‘breathtaking, intuitive (almost angelic) possession of the Truth and awareness of the supernatural which only a truly holy person can enjoy’. Addressing American Chestertonians twenty years later, Oddie was asked why there had been so little progress. He replied that for Chesterton’s cause to be taken seriously by the Church, there had to be a cult. ‘What the heck do they think we are?’ an audience member replied.

Confession: I’m rather fond of an essay I wrote three years ago about Citizen Kane. Excerpt:

Joe Kavalier [in Michael Chabon’s novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay] has a vision of comics as a powerfully hybridized endeavor: text and image, European and American, “popular” and “serious.” Similarly, [Pauline] Kael sees Kane as energized by the multiplicity of the forces that pass into and through it, as constituted by its tensions. What she realized was that there are more such tensions than a superficial viewing might reveal. It is easy enough to say that Kane, as a movie that portrays the downfall of a titan of print media, represents or somehow enacts the transfer of cultural power from print to film. And to say that would not be wrong. But what Kael uniquely understands is that that transfer is also a kind of homage — and more than an homage: a continuation of a flamboyant and entertaining social project by other means, in a new form.

If you’d like to read more, it’s here.