Paper and Memory

Over the past couple of weeks my wife Teri and I watched Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy — the 1979 miniseries, not the 2011 movie — and its 1982 sequel, Smiley’s People. Both are available on YouTube and, as far as I can tell, not streamed elsewhere, though depending on what region you’re in you might be able to buy DVDs.

They’re fantastic. Alec Guinness’s portrayal of the retired-and-then-unretired-and-then-reretired spy George Smiley is justly celebrated, but every actor in each series is superb. Some viewers will have difficulties with the pacing, which seems slow — but actually isn’t, if you accept the films’ invitation to think along with the characters: they spend a lot of time thinking, especially Smiley. The situations are immensely complex: Smiley must reckon with, as Donald Rumsfeld helpfully distinguished for us, known knowns, known unknowns, and unknown unknowns. When he pauses to think we viewers should pause to think also. It’s a chance to help our minds keep up with events.

Smiley’s world is a world of paper, a world in which the past is recorded on loose sheets, sheets gathered into manila folders, bound volumes, notebooks, ledgers. Searching through them requires a kind of laborious patience that few of us have today.

Files on computers are easy to delete but difficult to delete completely and irretrievably. Paper documents are surprisingly resilient: they can last centuries, perhaps even longer. Dropping them in water rarely renders them completely illegible. But they are highly vulnerable to fire. Messages in these series are encrypted and decrypted not by using something like the Diffie-Hellman key exchange but rather by using one-time pads, which are burned after use.

At one point in Tinker, Tailor a ledger is discovered with pages neatly, but noticeably, razored out (and presumably then burned). Absence of evidence and evidence of absence. Sometimes not finding the piece of paper you want can be as meaningful, and perhaps even more revelatory, than finding it.

When that happens Smiley knows what to do: Talk to the people with good memories. And the people he works with remember a great deal. They have, after all, been trained to observe and recall what they observe. Questioned by Smiley, they go into playback mode, narrating with precise detail long sequences of events. And often they don’t know, as they narrate, what piece of information will unlock a mystery.

When paper fails, memory; when memory fails, paper. A discerning, attentive, wise person can employ those two kinds of resource to bring down a whole network of spies. It was a different world.

Also, people smoke a lot in these films.

We also took time to re-watch, for the first time in decades, The Spy Who Came In from the Cold (1965), the first film to be made from a le Carré novel, and a cynically brilliant one. As we left it I found myself musing that the Alec Guinness Smiley stories could have been ever better if they had been made in black and white with cinematography by Oswald Morris.

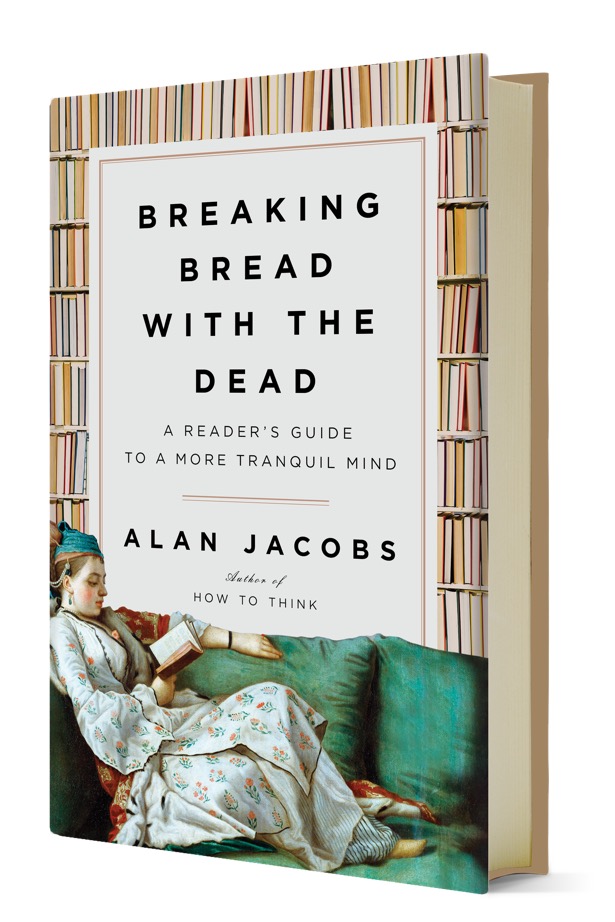

The book is out! Please buy dozens of copies for yourself and tell hundreds of people to buy dozens of copies for themselves.