Jubilee, and Knell

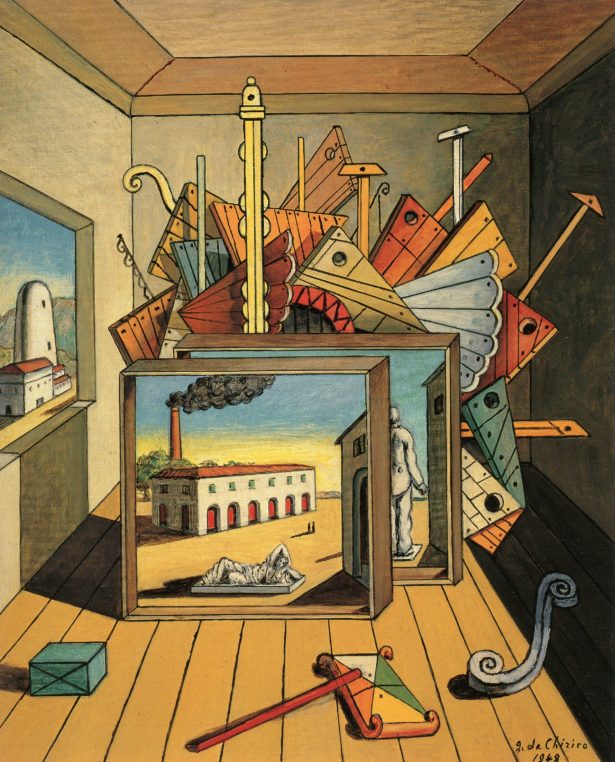

Giorgio de Chirico, Metaphysical Interior with a Factory (1969)

Giorgio de Chirico, Metaphysical Interior with a Factory (1969)

An except from Memory Police, by Yoko Ogawa:

The disappearance of the birds, as with so many other things, happened suddenly one morning. When I opened my eyes, I could sense something strange, almost rough, about the quality of the air. The sign of a disappearance. Still wrapped in my blanket, I looked carefully around the room. The cosmetics on my dressing table, the paper clips and notes scattered on my desk, the lace of the curtains, the record shelf — it could be anything. It took patience and concentration to figure out what was gone. I got up, put on a sweater, and went out into the garden. The neighbors were all outside, too, peering around anxiously. The dog in the next yard was growling softly.

Then I spotted a small brown creature flying high up in the sky. It was plump, with what appeared to be a tuft of white feathers at its breast. I had just begun to wonder whether it was one of the creatures I had seen with my father when I realized that everything I knew about them had disappeared from inside me: my memories of them, my feelings about them, the very meaning of the word “bird” — everything.

“The birds,” muttered the ex-milliner across the way. “And good riddance. I doubt anyone will miss them.” He adjusted the scarf around his neck and sneezed quietly. Then he caught sight of me. Perhaps recalling that my father had been an ornithologist, he gave me an awkward little smile and went off to work. When the others outside realized what had disappeared, they too seemed relieved. They returned to their morning duties, leaving me alone to stare at the sky.

The little brown creature flew in a wide circle and then vanished to the north. I couldn’t recall the name of the species, and I found myself wishing I had paid better attention when I’d been with my father at the observatory. I tried to hold on to the way it looked in flight or the sound of its chirping or the colors of its feathers, but I knew it was useless. This bird, which should have been intertwined with memories of my father, was already unable to elicit any feeling in me at all. It was nothing more than a simple creature, moving through space as a function of the vertical motion of its wings.

That afternoon I went to the market to do my shopping. Here and there I saw groups of people holding cages, with parakeets, Java sparrows, and canaries fluttering nervously inside, as if they knew what was about to happen. The people holding the cages were quiet, almost dazed, perhaps still trying to adjust to this new disappearance.

Each owner seemed to be saying goodbye to his bird in his own way. Some were calling their names, others rubbing them against their cheeks, still others giving them a treat, mouth to beak. But once these little ceremonies were finished, they opened the cages and held them up to the sky. The little creatures, confused at first, fluttered for a moment around their owners, but they soon were gone, as if drawn away into the distance.

When they were gone, a calm fell as though the air itself were breathing with infinite care. The owners turned for home, empty cages in hand.

And that was how the birds disappeared.

Recently I listened to a This American Life story about people with HSAM: Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory, one of the forms of hyperthymesia. Some articles I’ve seen online say that only around 60 people in the world have HSAM — here’s one — but I had a friend once who possessed many of the characteristic traits. If you asked him about a date from the past, chosen at random, he would tell you what the weather was that day in northern Illinois and what the headlines were in the Chicago Tribune (of which he was a faithful reader for decades). And he was always — always — correct.

He didn’t have a perfect memory for everything, though: my memory for conversations usually excelled his: together, we would recollect some dinner with friends, or an academic meeting, and while he could describe the whole surround of the event I was better at remembering precisely who said what and when. I was also better at recalling the source of quotations, and I know more poems by heart than he did, so as a general rule my retention of anything linguistic was better, but he dramatically surpassed me in every other kind of memory. Between the two of us we could do one hell of a reconstruction job on anything we had experienced in common.

I enjoyed my friend’s memory — it was like having constant access to a really cool party trick — but it had one down side: you could never convince him that he had misinterpreted anything that he remembered. The fact — and it was indeed a fact — that he could describe everything that happened on a given day convinced him that his understanding of what happened that day was more reliable than anyone else’s. After all, did he not have so much more information at his fingertips? Indeed he did; but that didn’t mean — or so I tried, unsuccessfully, to argue — that he had sifted that information with the requisite tact and nuance and care.

If I disagreed with his interpretation of something he would overwhelm me with a recitation of facts that I did not recall. The only time I gave him pause was when I pointed out that there were certain poems that we disagreed about the meaning of — but I knew those poems by heart and he didn’t. Did that in itself make me right? He agreed with me that it did not. But he didn’t translate that agreement into other venues of memory. I’ve never known anyone it was less possible to persuade, and that had almost everything to do with the excellence of his memory.

Emily Dickinson to her sister Elizabeth Holland, December 1882:

Mother has now been gone five Weeks. We should have thought it a long Visit, were she coming back — Now the “Forever“ thought almost shortens it, as we are nearer rejoining her than her own return — We were never intimate Mother and Children while she was our Mother — but Mines in the same Ground meet by tunneling and when she became our Child, the Affection came — when we were Children and she journeyed, she always brought us something. Now, would she bring us but herself, what an only Gift — Memory is a strange Bell — Jubilee, and Knell.

STATUS BOARD

- Work: The first book I’ll teach this fall is Augustine’s Confessions, which is, of course, about memory.

- Music: Every morning when I wake up my memory retrieves a song — a different song each day, though I’m sure there has been repetition over the decades, since the number of days I’ve lived exceeds the number of songs I have heard. (This has been happening my whole life, I think.) On any given morning it could be something that I have heard recently, but it’s far more likely that it will be a song I haven’t thought of in years and years. This morning it was The Beatles’ version, featuring Ringo, of the old Carl Perkins song "Honey Don’t." Sometimes I think I should write these down, but I have a superstitious resistance to doing that; I'm afraid this strange little gift will become shy and withdraw itself if it becomes a matter of record.

- Reading: Still working through, and meditating on, Arendt’s On Revolution.

- Food and Drink: Protein drinks. I hate my life.