In Which Kafka and Wombats Make An Appearance

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Equilibrium, 1932

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Equilibrium, 1932

There is a fairly lengthy article in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy on the vexed question of what exactly holes are — or are not. “If holes are particulars, then they are not particulars of the familiar sort. For holes appear to be immaterial: every hole has a material ‘host’ (the stuff around it, such as the edible part of a donut) and it may have a material ‘guest’ (such as the liquid filling a cavity), but the hole itself does not seem to be made of matter. Indeed, holes seem to be made of nothing, if anything is.”

A related point: Researchers have discovered precisely how wombats manage to make cubical poop. because they do indeed make cubical poop. Dr. Scott Carver had the honor of making the inevitable but still excellent joke: “Our research found that these cubes are formed within the last sections of the intestine – and finally proves that you really can fit a square peg through a round hole.”

Please don’t neglect to read this important press release from the Jewish Space Laser Agency. What, you have something better to do?

I wrote a post last week on old age and our technocracy’s poor calculations of a life’s value, and similar themes seem to be in the air. For instance, here’s my friend Drew Bratcher with a lovely essay on the hymns that filled his great-grandmother’s heart and soul:

It wasn’t mainly aesthetics, sentimentality, or wonder for wonder’s sake, that made hymns about heaven so dear to her. It was the hope they articulated, the future they described. It was their promise of a better life than the one she deserved or had endured. It was their assurance of a final judgment and of an eternal rest, one that she believed awaited her — as it awaited all those who’d placed their trust in Christ — on, as one of her favorite hymns put it, “the farther shore.””

And here’s Maureen Swinger on the beautiful life of her severely disabled brother Duane:

And that’s why Duane’s story is more than a tale of a great kid growing up in a caring family, and more than a testament to the abstract idea that all people’s lives have value. There are people living bravely with disabilities everywhere. Many have strong networks of care, and many are devastatingly alone. Are the healthy individuals who pass them by, though, less alone? Perhaps it is isolation from humanity that breeds the sort of clinical coldness that suggests the removal of suffering by removing the one who suffers. Could the quest to eliminate others’ suffering be a disguised attempt to distance ourselves from pain, because we fear there is no way through it?

In one of my classes I’m teaching the stories of Franz Kafka, and when I stand in front of the class I find myself remembering something Auden once wrote about Kafka:

Though the hero of a parable may be given a proper name (often, though, he may just be called ‘a certain man’ or ‘K’) and a definite historical and geographical setting, these particulars are irrelevant to the meaning of parable.... The ‘meaning’ of a parable, in fact, is different for every reader. In consequence there is nothing a critic can do to ‘explain’ it to others. Thanks to his superior knowledge of artistic and social history, of language, of human nature even, a good critic can make others see things in a novel or a play which, but for him, they would never have seen for themselves. But if he tries to interpret a parable, he will only reveal himself.

Sobering! — but I fear true. What self-revelation am I inadvertently making as I talk to my students about Kafka?

That essay, by the way, contains a wonderful little anecdote from one of the most peculiar episodes in Auden’s career, the brief period around the end of World War II that he spent as Major Auden:

Sometimes in real life one meets a character and thinks, ‘This man comes straight out of Shakespeare or Dickens’, but nobody ever met a Kafka character. On the other hand, one can have experiences which one recognizes as Kafkaesque, while one would never call an experience of one’s own Dickensian or Shakespearian. During the war, I had spent a long and tiring day in the Pentagon. My errand done, I hurried down long corridors eager to get home, and came to a turnstile with a guard standing beside it. ‘Where are you going?’ said the guard. ‘I’m trying to get out,’ I replied. ‘You are out,’ he said. For the moment I felt I was K.

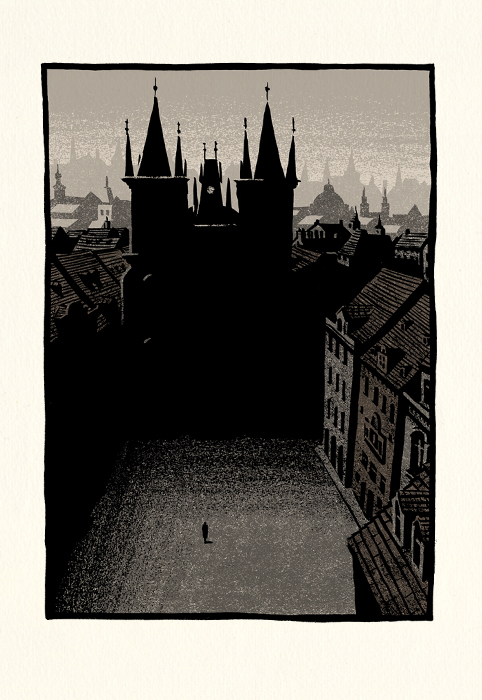

Illustration by the wonderful Bill Bragg