Harmonies and Dissonances

Updating the furnishings of a 1960s church

Updating the furnishings of a 1960s church

I’ve been blogging away, thanks to the support of people who have bought me dragons. (N.B. I could always use more dragons.) But I also have a few essays coming out in periodicals in the coming months – I’ll link to them here when they become available.

Ian Leslie’s recent essay on Peter Jackson’s Get Back is one of the very best things I have ever read about the Beatles. And I’ve read a lot about the Beatles.

Worth examining in detail: Lewis and Clark’s map of the vast spaces west and north of St. Louis.

Shocking news: Haggis is English, not Scottish.

Listening to Matthew Syed’s podcast Sideways I learned of the work of a scholar at Cambridge University named Ian Cross. Cross and his colleagues have discovered that when two people talking agree with each other, their voices tend to converge in pitch; and, conversely, when they disagree their voices tend to diverge in pitch. That is: agreement is literally harmonious, and conflict is literally dissonant.

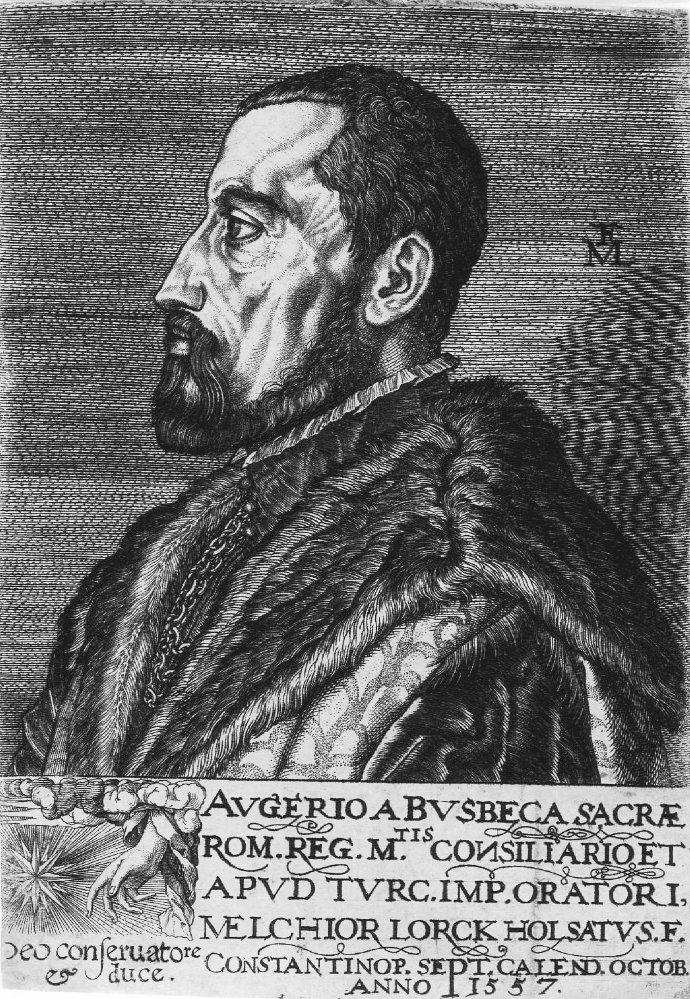

Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq (1522-1592) was a Flemish diplomat who did two amazing things. The first is this: When he was an ambassador at the Ottoman court in Istanbul, he met some men from the Crimea who spoke a very curious language. Busbecq recorded some of their vocabulary and the lyrics to a song. It turns out that they spoke a variant of Gothic – a language which had otherwise died out centuries earlier.

Busbecq’s other achievement? He became fascinated with a flower that he called the “tulip” – having mistakenly appropriated the Turkish word for “turban,” tulipant – and sent some bulbs to a Dutch friend, who acclimated them to the Northern European climate, and … well, we know the outcome.

Jacob Marrel, ca. 1635-45

Jacob Marrel, ca. 1635-45