Cities and Ruins

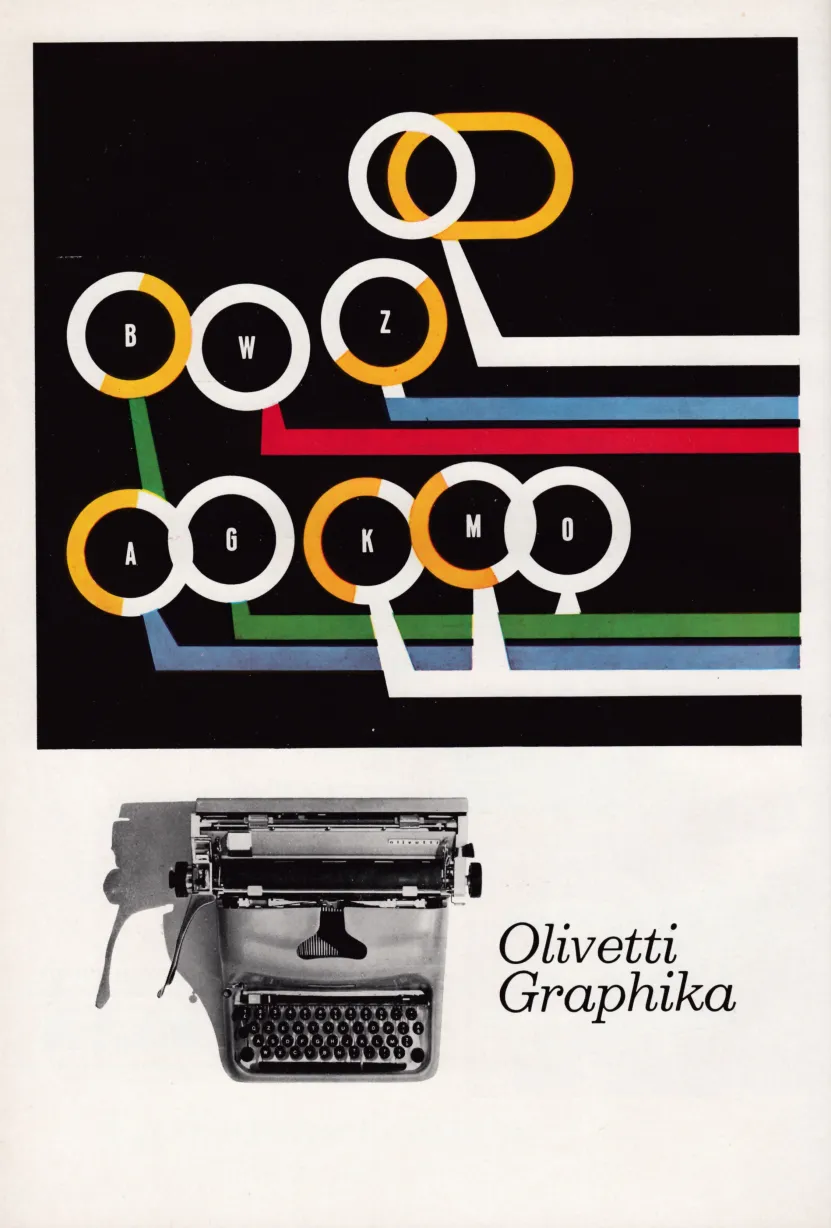

How Stephen Heller lost his heart at the Olivetti store

I’ve finished (for now anyway) my blog-through of Augustine’s City of God, focusing on his treatment of “the two cities.” I’ve given them all the tag CD23 – CD for Civitas Dei. I’m thinking about doing this with other books – I like the way the commitment to blogging slows down my reading and helps me to think better about what I read.

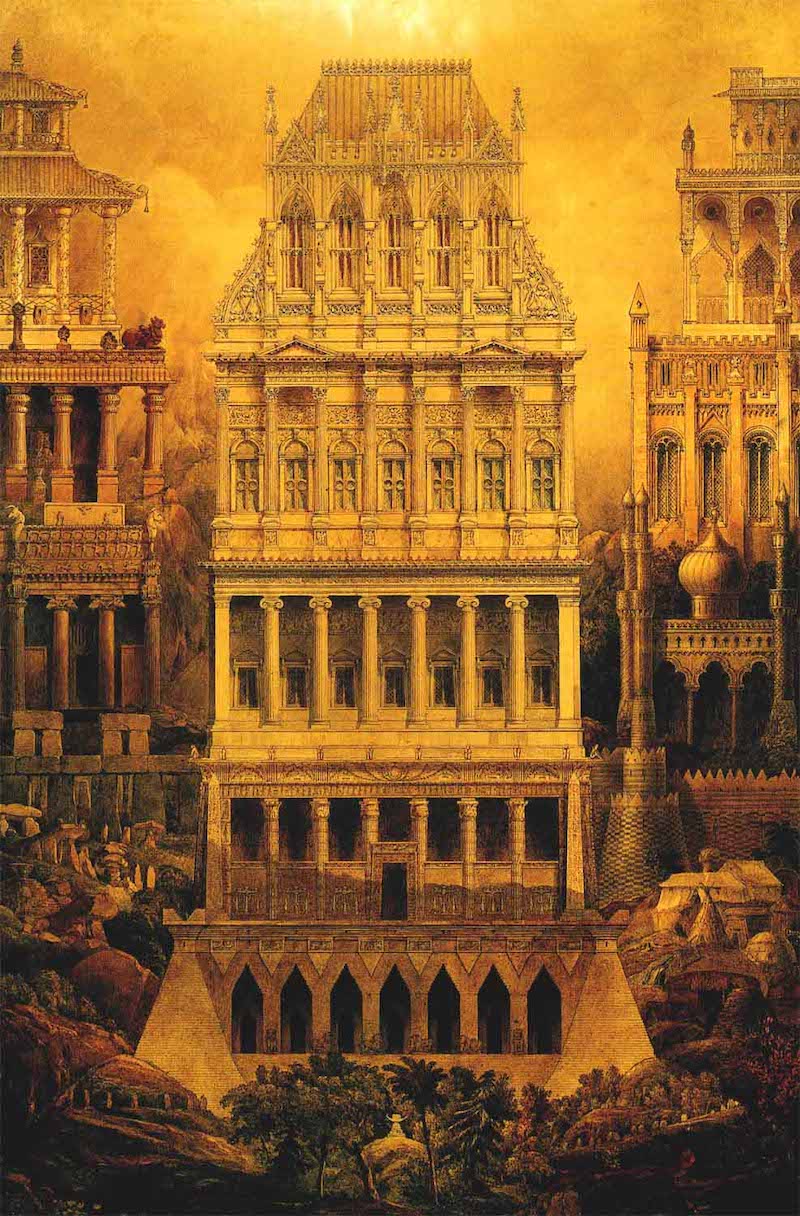

What you see above is one of the architectural fantasies of Joseph Gandy, a colleague of Sir John Soane, whose curious little museum is one of my favorite places in London. One of Gandy’s paintings, made just before the accession of Queen Victoria, imagines an Imperial Palace. Here’s the description by James Morris, in Heaven’s Command:

It was to be a building of overpowering elaboration, domed, pedimented, turreted, colonnaded, upheld by numberless caryatids, ornamented with urns and friezes and mosaic pavements and sunken gardens and ceremonial staircases, and allegorically completed by the marble columns, toppled ignominiously in the forecourt, of earlier and more transient sovereignties.

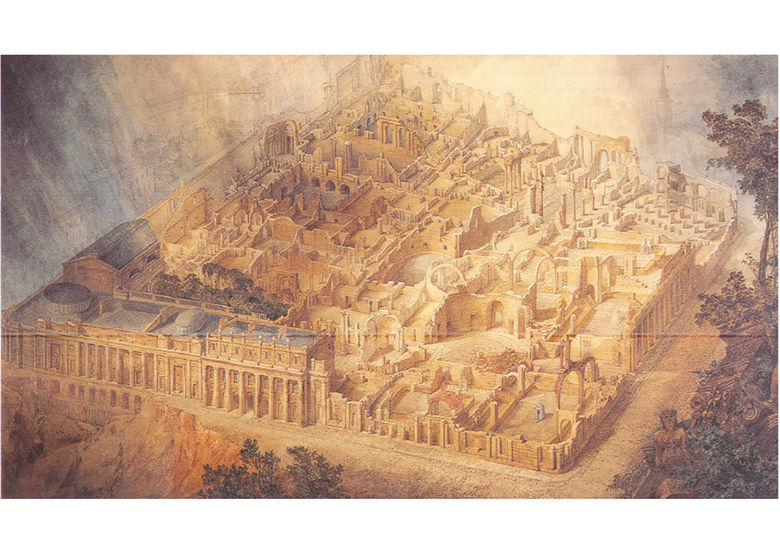

But perhaps Gandy was not convinced that the British Empire was immortal either. Here’s his depiction of the Bank of England in ruins:

More about the marvelously weird Gandy here.

By the way, when I called the author of Heaven’s Command James Morris, I don’t believe I was committing the mortal sin of deadnaming. James, famously, became Jan, and I knew and loved her writing for many years before I discovered that she had been one of the first well-known people to undergo a sex-change operation (as it was then called). In fact, there was a period in which I enjoyed reading Jan Morris and knew that a journalist named James Morris had been a part of the Norgay-Hillary Mount Everest expedition – he sent the telegram to his bosses at the Times of London announcing the achievement of the summit; it arrived on the morning of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation – without realizing that Jan and James were one person. She began her magnificent Pax Britannica trilogy in the 1960s, when she was still James, and when she oversaw the publication of the beautifully printed though indifferently illustrated Folio Society edition in 1992 she kept the name James on the cover. So I am here honoring her own decision.

The New York Times is very enthusiastic about Dolby Atmos, or what Apple calls “Spatial Audio.” Sasha Frere-Jones isn’t convinced:

What you now see on your phone as Spatial Audio, or Dolby Atmos, both complete with corporate logos, is not Atmos as you hear it in a movie theater. What you have on your phone is a “fold down” of all the x, y, z axis metadata bundled into a Atmos mix, the information that sends pieces of audio to specific speakers, when there are actually lots of speakers present. Your phone has one speaker and a stereo output. Apple’s Spatial Audio software uses perceptual tricks of EQ and placement, to fold down the multi-speaker experience into a binaural mix for that stereo output. What does this actually sound like? Jon Leidecker, of Negativland and Wobbly, and a former Dolby Atmos employee, described it as a “big reverb button,” and I think this is fair. In March, someone named KamranV at Digital Music News wrote: “At the risk of sounding reductive, Atmos+Apple Music sounds bad.”

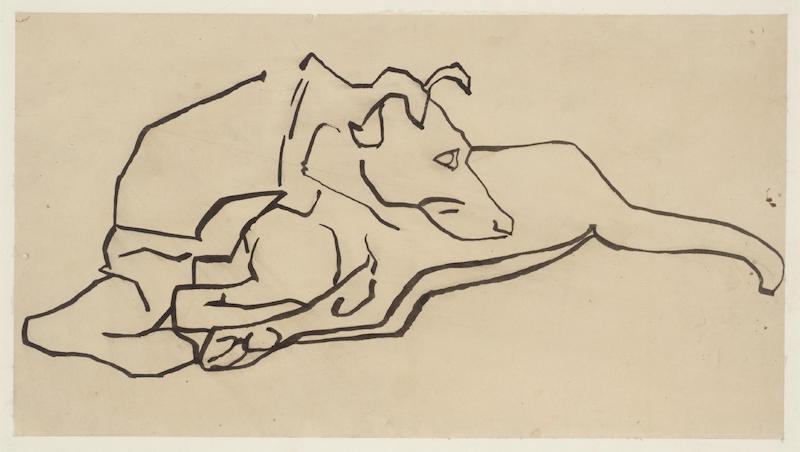

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. I think everything Gaudier-Brzeska made was touched by magic. Hugh Kenner celebrated him in The Pound Era but I think he is still neglected.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. I think everything Gaudier-Brzeska made was touched by magic. Hugh Kenner celebrated him in The Pound Era but I think he is still neglected.