Art Out of Time

Early Computer Art in the 50’S & 60’S

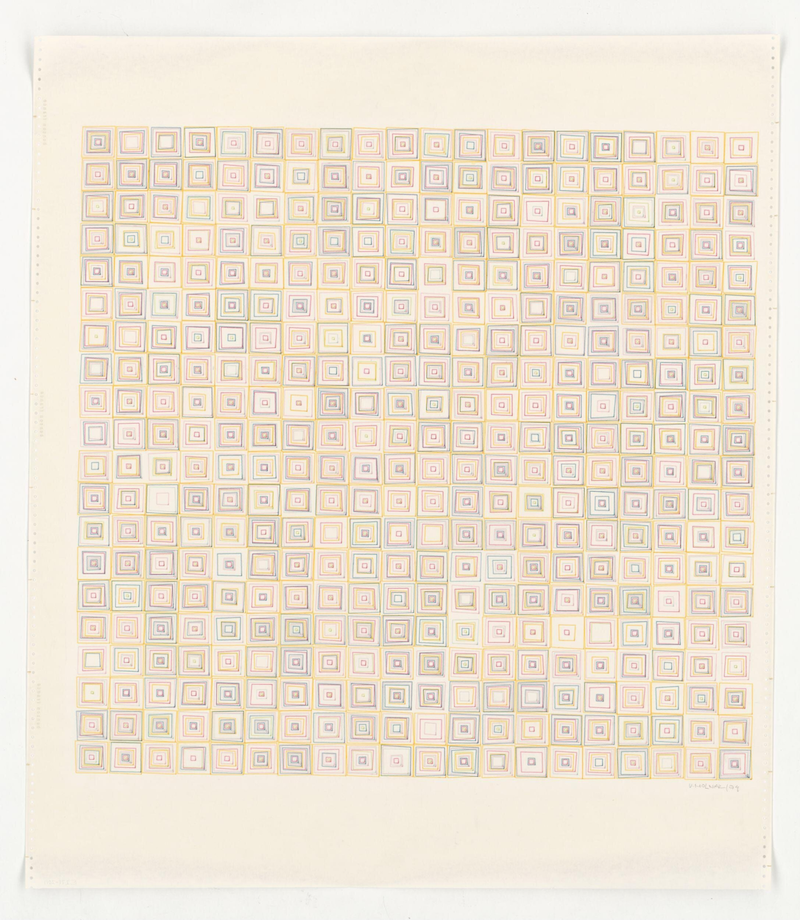

(Des)Ordres (1974), Vera Molnar

(Des)Ordres (1974), Vera Molnar

Depending on whom you ask, this combination is either as congenial as shrimp and grits or as regrettable as a bad marriage. The food writer Adrian Miller once noted, “It may be the most controversial soul food coupling since someone decided it was a good idea to marinate dill pickles in Kool-Aid.” [Stephen] Satterfield, who is thirty-nine, first encountered the dish as a family tradition: in Mississippi, where his maternal grandmother was born, the river was full of catfish, and spaghetti was cheap. In 1946, she and his grandfather followed the Great Migration route north to Gary, Indiana. When Stephen was growing up, his father often fixed catfish and spaghetti for Sunday dinners and for church fish fries.

Satterfield didn’t realize the pairing’s wider significance until he was getting ready for an episode of “High on the Hog,” which refracts the history of the United States through the lens of Black food. Miller, who appears in the series, had an explanation: catfish and spaghetti originated in the Deep South in the late eighteen-hundreds, as Italian immigrants settled in Mississippi and Louisiana. Black Southerners adopted spaghetti, and came to consider it, like coleslaw or potato salad, a pleasing side dish to fried fish.

Never tried it, but now I have to.

The quintessential artist, Mozart served the great human simplicities and shaped his great lies to show us the truth. From childhood, music was his native language and his mode of being. He thought deeply but in tones, felt mainly in tones, loved in tones, and steeped himself in the worlds he was creating with tones. From a life made of music he wove his music into the fabric of our lives. More and more toward the end, as he reached toward new territories, his art found a consecrated beauty that rose from love: love of music, love of his wife, love of humanity in all its gnarled splendor, love of the eternal yearning for God in the human heart. His work served all that. Whatever his image of God by the time he reached the Requiem, it was taken up in his humanity, and his humanity was for all time, and it was exalted in his art.

Twice in this magnificent biography, Swafford points out that if Mozart had lived only to the age of seventy-one – his sister and his wife lived longer, his father lived almost as long – he would’ve died in 1827, the same year as Beethoven. That’s a remarkable possibility to contemplate.

He wrote so much music in his thirty-five years not only because he was uniquely prodigious of imagination – that, but not only that: he was also scrupulously professional. as James Wood comments in a recent essay,

How was this quantity of unworldly and imperishable music achieved in such conditions? The endlessly prolific pinnacles seem all the more astonishing, all the more unreachable, in our era of padded fellowships. George Steiner used to be aghast that we now possess the cheap freedom to listen to a difficult late Beethoven string quartet while eating our breakfast. Surely the miracle is that composers like Bach and Mozart might have written such work while eating their breakfast. There’s plenty more where this came from, they seem to be saying, in their every bar.

She once said that art that was ‘alive’ would always be in some sense modern, and she has been vindicated. Nearly thirty years after her death, her bowls and bottles haven’t dated.... Rie remains curiously outside time or, indeed, place. There are lingering memories of Continental modernism, some touches of the Viennese in her work, but it doesn’t look like either, nor does it seem in any obvious way English. This exhibition brings out qualities that more limited surveys, or the many occasions on which she has been shown alongside her friend and fellow refugee Hans Coper, have obscured. It is a pity that the accompanying book hasn’t been better edited. The essays, although for the most part strong individually, repeat much of the basic information and occasionally contradict one another. Overall, however, the show is a joy. There is a powerful inevitability about Rie’s best work. I found myself thinking of the gnomic phrase the antiquary William Stukeley used to describe Stonehenge: ‘It pleases like a magic spell,’ mysterious but charming.