A Magic Number

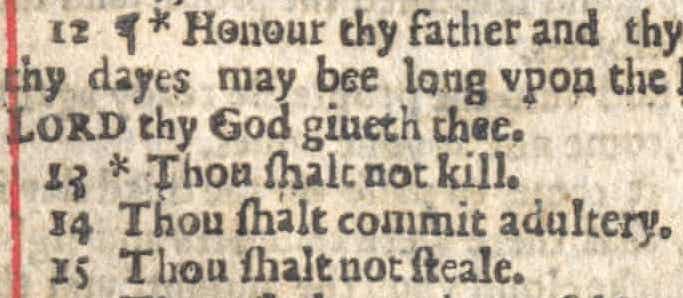

A number of editions of the English Bible are known today solely for their errors. As F. F. Bruce explains in his wonderful history of the Bible in English, in 1717 an edition of the Bible featured a heading identifying “the Parable of the Vinegar” instead of “the Parable of the Vineyard,” and so became known as Vinegar Bible. More ominously: in the King James version Mark 7:27 says “Let the children first be filled,” but an edition printed in Oxford in 1797 got one letter wrong: “Let the children first be killed” — thus earning the name the Murderer’s Bible. Most notorious of all is the 1631 Bible which earned the name the Wicked Bible by presenting the Seventh Commandment thus: “Thou shalt commit adultery.”

I have compassion for those poor typesetters, known today only for their errors, as emails have been pouring into my inbox. If you were to put all the email I have received in response to this newsletter prior to last week in one pile, and all the email I have received in the past week in another, the second pile would be larger. Why? Because last week I misspelled the name of the Vancouver Island town of Tofino as Torino.

Dear reader: In case the Will to Correct seizes you in response to errors in this or some future newsletter, I want you to be aware of two things. First, I usually see the errors myself immediately after I post the newsletter – such is the way of the world – and then fix them, so the online version of the newsletter will typically be error-free; you could perhaps check that before writing me. Second: If you see an error you want to correct, please bear in mind that a few dozen people just might have done the job for you already.

Last week I was able to spend a few days of quiet retreat at my happy place, the co-sponsor of this newsletter, Laity Lodge. I took some pictures.

That's Bob Dorough. He was a jazz musician, a pianist, singer, and composer, who died two years ago at the age of 94. He had a wonderfully varied career, playing with such greats as Miles Davis and Blossom Dearie and even Allen Ginsberg, but I came across his work in a different way.

I have strong responses to the ways that musical recordings are engineered. Anything produced as a result of the so-called loudness war I simply cannot listen to — I rip the earphones from my ears or fly across the room to shut down the stereo system. By contrast, I love recordings that are spacious in their sound, with a clear distinction among instruments and a vivid soundstage. My go-to test recording, whenever I want to know what a pair of speakers or headphones sounds like, is “Dos Gardenias” by the Buena Vista Social Club. I love Ray Charles’s Atlantic recordings from the 1950s, and Theolonius Monk’s classic 1962 recording Monk's Dream, and of course almost anything by the Beatles, but especially their mid-career stuff, Rubber Soul, Revolver. Though Radiohead succumbed often to the loudness curse, I love the open sound of “Reckoner.” I think about recording engineering often, and I had read somewhere — I don't remember where, maybe some audiophile discussion board — a comment that one of Bob Dorough’s songs was especially well-recorded.

Which leads me to the most curious part of Bob Dorough's long career. In the 1970s he started working for Schoolhouse Rock: He’s the man to whom we owe the irresistible “Conjunction Junction” — though mad props also to Jack Shelton’s inimitable vocal — and the surprisingly Schubertian “Figure Eight.” Twenty years ago the great jazz critic Gary Giddens wrote an essay about Dorough in which he narrates how he learned about this Other Side of Dorough’s career:

I was having a high old time listening to Bob Dorough’s new record, Too Much Coffee Man (Blue Note), which may be his best, when my assistant Elora walked in and exclaimed with a slight interrogatory, “Schoolhouse Rock!?” She had never heard of Dorough, but she recognized the voice. I had never heard of Schoolhouse Rock, so she brought in her four-disc Rhino set and played her favorites, including a masterpiece, “My Hero, Zero,” noting, “You will not find anyone of my generation who does not know the words to ‘Electricity Electricity’ and ‘Conjunction Junction.’ ” She proved the point with a recitation augmented by a description of the animation that accompanied the songs when the short instructive cartoons appeared on television. Dorough was the series’ music director and wrote most of the songs. “I learned the multiplication tables from him,” Elora marveled. “We had great TV then.”

Dorough originally got the job by writing a multiplication song called “Three Is a Magic Number” — and that is the song that it supposed to have such a good sound. So I downloaded it and started listening.

Right from the beginning I could tell that it is very well-recorded indeed, which was a surprise for what's basically a children's song meant to be played on the TV rather than on a fancy stereo. But then as the song moved along something unrelated to the recording quality struck me.

In order to understand this, you need to know that my wife and I had a great deal of difficulty conceiving a child — I'll spare you the details — and then when our son Wesley was conceived it was a harrowing nine months waiting and hoping that he would be born safe and healthy. He was indeed, and rather against the odds, born safe and healthy, and he has been the light of our life ever since. We tried very hard to have more children, but that proved to be impossible because of the same circumstances that made his arrival such a doubtful event, and by the time we finally accepted that another child wasn't coming, we were on the old side for adoption.

Teri and I were married for twelve years before Wes came along, so every day I am grateful to God for his arrival and his presence in our lives. But I have to admit that I’ve sometimes felt a bit melancholy when we are around our friends with big bustling families. And I was going through one of those melancholy periods the first time I listened to “Three Is a Magic Number” — so I was very surprised when, about a minute into the song, after a few lines about tripods and tricycles, Dorough and his little ensemble sang this:

A man and a woman had a little baby

Yes they did

They had three-ee-ee in the family

And that's a magic number

That's a magic number. And it is. I listened and thought: It really, really is. So thank you, Bob Dorough, for that unexpected gift, a gift of renewed gratitude for the life we three share, for the family we are — even when Covid is separating us.

All this might help to explain an otherwise strange phenomenon: These days, when I think of the times-three tables, I get at one and the same time a small smile on my face and a small tear in my eye.