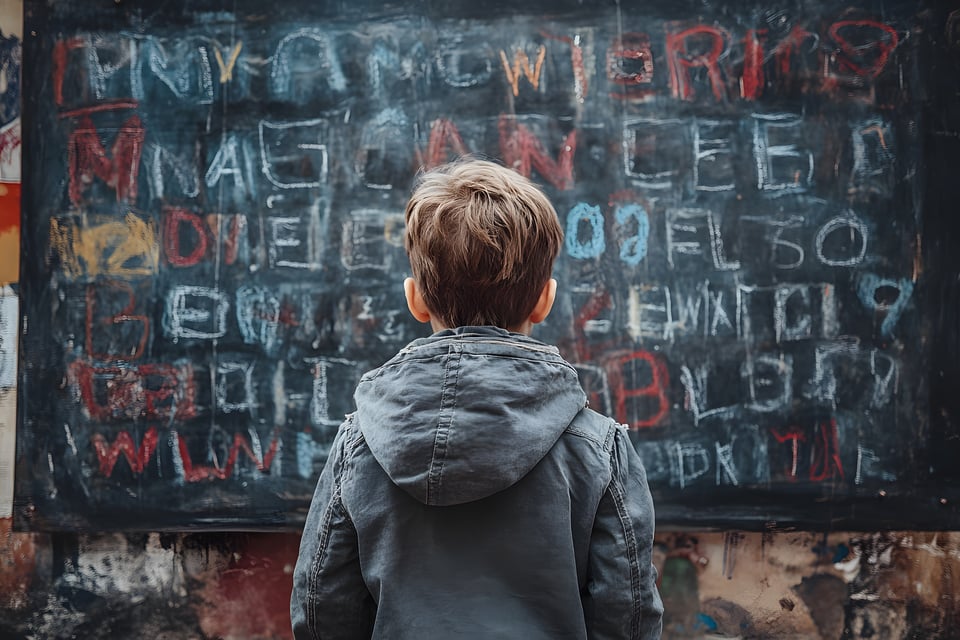

Designing for Dyslexia: Accessibility Requirements and Best Practices

October is Dyslexia Awareness Month, reminding us that accessible design directly influences how millions read and engage with digital content. Dyslexia impacts fluency, comprehension, and reading comfort, but careful accessibility practices can lower those barriers. Although there isn't a single “fix," practical steps based on WCAG 2.2 can enhance usability for people with dyslexia and promote inclusivity for all readers.

1. Use Tools Like HelperBird to Adjust Spacing When Testing

Crowded text is harder to read for many people with dyslexia. Tools such as HelperBird allow users to increase line spacing, letter spacing, and word spacing. These adjustments reduce visual crowding and help words flow more clearly across the page.

WCAG Reference: 1.4.12 Text Spacing requires that users be able to adjust spacing without losing content or functionality.

Best Practice: Support compatibility with these tools and avoid code that locks in spacing or line height.

2. Combine Magnification, Spacing Adjustments, and Reflow

Magnification enlarges text, but without spacing adjustments, it can still feel cluttered. Combining magnification with spacing adjustments enables users to view larger letters with increased space between them. Reflow is just as important; it ensures that when text is enlarged, content automatically rewraps to fit the viewport, rather than forcing horizontal scrolling.

WCAG References:

1.4.4 Resize Text requires text to stay readable when enlarged.

1.4.10 Reflow ensures zoomed content adapts without losing functionality.

Tip: Encourage users to combine magnification with HelperBird’s spacing tools. This pairing is often overlooked but very effective.

3. Reduce Glare with Softer Color Combinations

High-contrast black text on a bright white background often causes glare and visual fatigue. This can impact people who experience migraines and people with dyslexia, amongst others. Subtle shifts in color provide strong readability while reducing strain. Examples include:

Pair background:

#FAFAFAwith Text:#1A1A1APair background:

#F5F5F5with Text:#222222Pair background:

#ECECECwith Text:#1C1C1C

All of these exceed a 7:1 contrast ratio, meeting 1.4.3 Contrast (Minimum), while avoiding the harshness of #FFFFF black on #000000 white, while being imperceptible to non-disabled users.

4. Make Informed Font Choices

There is no single “best” font for dyslexia, although some claim otherwise. Research indicates that clear, simple fonts are more effective than decorative or highly stylized ones.

Good options: Use sans-serif fonts such as Arial, Verdana, and Tahoma.

Atkinson Hyperlegible: Developed by the Braille Institute, designed to increase distinction between easily confused characters. While helpful for some, it is not a universal solution. It is my personal favourite, however.

Caution: Using italics in even clear and simple fonts can blur letterforms and reduce readability. Use bold or underline instead, while making sure that these items are distinguishable from links/visited link text.

WCAG Reference: 1.4.8 Visual Presentation encourages flexibility in font and style.

5. Structure Layouts for Readability

Text alignment and layout choices significantly impact readability, just as font or spacing do.

Avoid right or center justification: Uneven line starts make it harder to track text. Left alignment creates a consistent eye anchor.

Avoid multi-column layouts: They create abrupt jumps in reading order, forcing extra effort to track where content continues.

WCAG Reference: 1.3.2 Meaningful Sequence ensures content flows in an order that makes sense.

6. Don’t Forget, Dyslexics use Screen Readers too!

Screen readers are often associated only with individuals who are blind, but many people with dyslexia or cognitive issues also use them as part of their regular assistive technology. Hearing text read aloud can enhance comprehension, reduce fatigue, and assist with proofreading. This indicates that screen reader compatibility benefits many more users than most teams realize. Ensuring proper heading structures, alt text, and semantic markup not only fulfills WCAG requirements but also supports people with dyslexia who depend on text-to-speech as a valuable accessibility tool.

Final Thoughts

Designing for dyslexia is about reducing reading effort and creating flexibility. Tools like HelperBird, thoughtful magnification with reflow, softer color contrasts, careful font and layout choices, and support for user customization all improve accessibility. These changes don’t just help people with dyslexia; they make digital experiences more comfortable for everyone.

Accessibility is not a one-time project. Maintaining it requires ongoing effort and organizational commitment. The W3C Accessibility Maturity Model emphasizes this by helping organizations track their progress over time, rather than just addressing individual issues.

Ultimately, the best way to enhance accessibility for people with dyslexia is to employ people who have dyslexia. Their lived experience provides insights that no checklist can capture. Including them in design, testing, and development processes ensures that solutions are grounded in real-world needs.

Add a comment: