When the wrong hands are the right hands

Nothing to see here, and everything to see here

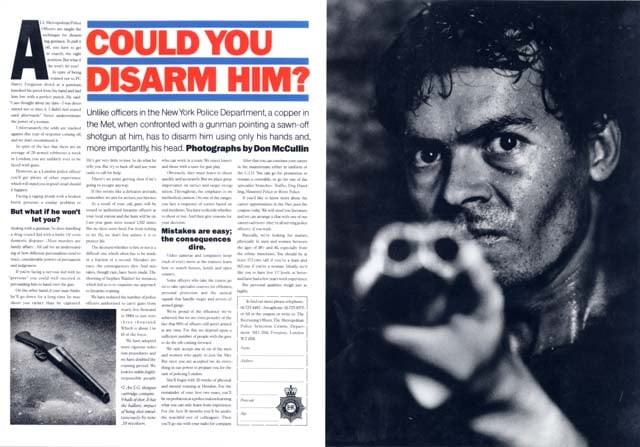

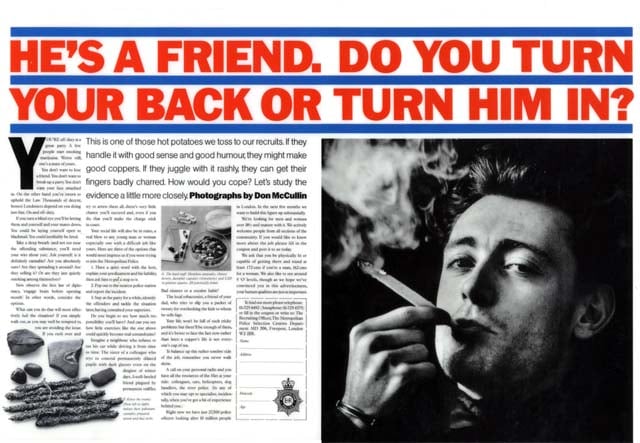

You can tell how old this ad is by the cut-out response coupon in the corner.

You can also tell how old this ad is because it’s from a time when people might have harboured positive feelings about the Metropolitan Police.

It’s a press ad, but I remember seeing this campaign on cross-track posters on the London Underground in the late 80’s. Big, bold, and broadcast. Also brilliant. Collett Dickenson Pearce in its pomp.

If you’re a service business, and your service is delivered in person to your service users by your people, then your people are the most important outlet for your brand. And it follows that the character traits of your people have to be perfectly in tune with the values of your brand. It doesn’t work otherwise.

And if the traits of your people are the values of your brand, then recruitment advertising is also brand advertising. You can’t separate the two.

These Met Police recruitment ads are brand ads by stealth. The approach is stealthy even though it’s staring you in the face. The subtle, seductive stealth of the ads comes from the fact that most readers aren’t in the target audience. I don’t want to be a copper. But I’m intrigued enough to read it. And I read it with my guard down because it isn’t meant for me. If I overheard someone say something when they didn’t think anyone was listening, I’d be inclined to believe that they were speaking the truth. There’s a similar effect with this kind of recruitment advertising. It’s not trying to sell me anything. I’m seeing something that I’m not meant to see. It’s probably true.

And yet it’s obvious that I am meant to see it because it’s running in very public media. Back in the 80’s, maybe there wasn’t a more efficient way to reach potential Met Police recruits. Nonetheless, I’m sure that the planners behind this campaign knew that they were getting brand bang for their recruitment buck.

This idea of publishing “private” recruitment messages in very public places is a legitimate brand-building strategy for any people business.

Stealth on steroids

This Met Police campaign from the late 80s couldn’t go viral. The means didn’t exist. The ads might have generated a ripple of PR coverage - they contain plenty of angles for an interested journalist. But word of mouth back then wasn’t turbo-charged by social media.

Nowadays it is. So this strategy of using recruitment ads to promote a brand gets two bites at the apple. You can run supposedly private messages in public places. And you can make the creative interesting enough for people to share it.

That’s what Google did with this ad to recruit engineers.

They ran it on billboards in Silicon Valley. There’s nothing to tell you who’s behind the ad. There’s no message as such. But there is a call to action. In fact that’s all there is. The ad is a puzzle, which, for the right kind of person, is an irresistible call to solve it.

The answer to the puzzle was a numerical website address at which those who had solved it could apply to be a Google engineer. But to solve the puzzle you needed both some mathematical nouse and the ability to write the code to apply your logic.

Apparently there was a more difficult problem to solve when you visited the site. Only then did you find out that it was a recruitment stunt for Google.

Either that news leaked, or Google leaked it, and the ad and the story behind it got shared a lot. A few of the right people solved the puzzle and maybe applied to join Google. A lot of the “wrong” people saw the ad, read the story, and came away thinking that Google is a smart company hiring smart people; that’s a company to trust and admire.

You can tell how old this ad is because it’s from a time when people might have harboured positive feelings about Google.

We do stuff

Lots of companies talk a good culture game. Not many deliver. Genuinely strong cultures attract a lot of interest, therefore. So, in the same way that recruitment messages can be brand messages for a people business, internal culture messages can be brand messages too, if they find their way into the outside world.

Copy that’s ostensibly written for employees can push all the right buttons for potential customers. It pushes those buttons harder because the prospect’s guard is down. “I wasn’t meant to see this.”

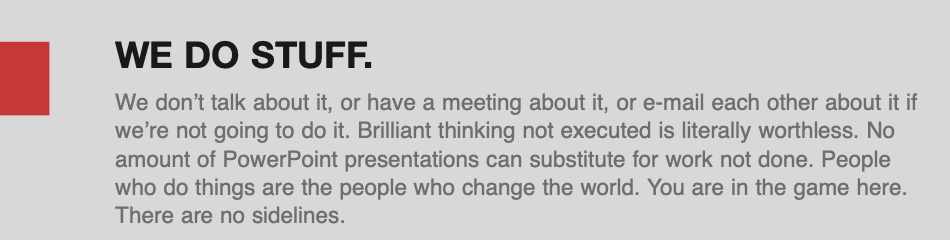

Plenty of employee handbooks have gone viral. Like I say, evidence of an unusually strong culture is broadly interesting. My favourite is the old Crispin Porter Bogusky (CPB) employee handbook. The full document is available to read or download. When this handbook was written, CPB was arguably the hottest ad agency on the planet, operating out of Miami. Someone I trust and respect worked there and loved it. The handbook tells the truth of that time.

It was widely shared because of the way that truth was written: beautifully.

Every section spoke volumes about the agency’s people and its culture. And therefore every section pushed all the right buttons for a potential client. I’d want to work for an agency that “does stuff.” And, if I were a client, I’d want to hire an agency that “does stuff.” I’d also want to hire an agency that has its feet on the ground when it comes to money:

When the wrong hands are the right hands

If you’re a people business, your employer brand is your customer brand. And you have the option to make this a comms strategy. You can make narrow comms available in broad media. You can create compelling stuff targeted at employees or recruits and make sure that it gets into the “wrong hands,” which are actually the right hands because they’re the hands of potential customers. And you can benefit from the guard-down stealth of comms that the intended audience wasn’t meant to see (but actually was.)

Crispin Porter Bogusky is now known as just “Crispin”. I note that it’s part of the Stagwell group, which was exposed recently for its shady work for the Israeli government.

You can tell how old the CPB handbook is because it’s from a time when people might have harboured positive feelings about the agency; a time before it sold (unwittingly I’m sure) to masters whose behaviour it can’t control.

Maybe try this too: Shiny rectangles - a post about the importance of style to b2b and service business brands.

Add a comment: