What did you see?

Talking

The best part of my job is talking to people, which is an odd thing for me to say. I’m quite shy and I’m an introvert. Small talk has never come easy, although I used to try harder when I was younger. These days I tend to save my energy and withdraw from superficial exchanges. I’m not an impressive person on first meeting.

It’s a different matter if someone is open to a more meaningful conversation. I’m just as unimpressive, but I’m all-in if I sense that someone is up for trading some truths; if they’re in the mood to be profound.

That’s why talking to people is the best part of my job. My stakeholder interviews are always profound, at least in part. As unimpressive as I am, I’ll back myself to get us into profound territory.

How does that work, unimpressive shy boy?

Being unimpressive is an advantage for an interviewer. The kind of charisma that breaks the ice at parties is a handicap for conversations that depend on someone being unguarded and perhaps even vulnerable. In a proper conversation, what impresses people most is not that you’re sharp or funny, but that you make the effort to get them. I’m rubbish at small talk, but I’m genuinely interested if someone is ready to open up. I assume (correctly) that they have more interesting things to say than me. I ask pointed questions and then keep my mouth shut and properly listen to the answers. I’ll probe more deeply when I sense that someone has left the door ajar and is inviting me in. All the best chat-show hosts do this and I copy them.

Getting people to open up and be profound is the craft skill that I’m most proud and protective of. I reckon this is where 75% of my value lies. The rest comes from making sense of it all.

This is why I’m not overly concerned about AI. Caring, listening, and empathising to really get people are off-the-AI-grid human abilities. The kind of strategy work I do involves just a small bit of science. It’s partially an art. But mostly it’s the humanities.

Shirking

I’ve watched other strategists try to use AI applications to speed up the sense-making part of the job. They’ll feed their interview transcripts into an LLM and let it identify the themes. And I can see the temptation. These apps cover a lot of ground in no time at all.

This kind of efficiency is seductive but it’s counterproductive, for two reasons. Firstly, when something covers a lot of ground more quickly than you, it leaves you behind. If you outsource (abdicate) the analysis to AI, you get quick answers but you don’t do the working out. More often than not, the working out is the most valuable part of the process. If you really knew what you were doing, you wouldn’t be so eager to bypass it. Strategy work always involves a period of agony, out of which comes epiphany. The agony is the point. And if the Covid pandemic taught us anything, surely it’s that efficient processes tend to be fragile processes.

Secondly, quick answers aren’t the best answers. Using AI might get you to a good place quickly. It might get you to second or third base. But it won’t hit you a home run. I’ve seen an LLM produce a decent summary of a bunch of interviews, at the same time as completely missing the one comment from one stakeholder that unlocks the whole project.

AI won’t hit you a home run, and you’re not going to hit a home run either if you start from second base without knowing how you got there. I’ve seen this happen. I’ve seen strategists stuck on second base because they haven’t done the work to get there. Some people swear that AI is a fabulous creative sparring partner. Good for them if that’s the case, but it’s not for me.

I believe that this type of efficiency will turn out to be seriously overrated, that it actually erodes value. My strategy, as most others join the AI foolsgoldrush, is to double-down on “manual labour” and be proud of it. I don’t need to convince the market. I don’t need to convince you. I just need several clients a year to see things my way.

Boring

It’s clear that I have an aversion to using AI for creative tasks, which includes strategy work. I should probably make my ignorance clear too, in case it isn’t obvious.

I’ve never even experimented with AI for strategy work. I know people who have. I know people who swear by it. I don’t, partly because my gut is telling me to leave well alone. I don’t see that anyone has properly thought through where this AI mania will end up. But mostly I don’t use it because I find the whole idea boring. I find simulations of any kind boring. I’ve quickly bored of every computer game I’ve ever played. I can see that other people find gaming deeply rewarding, but it doesn’t do it for me. Using AI for strategy or creativity is the same. Most people are mad for it, apparently, but the whole idea leaves me cold.

I listened to Steven Pinker talk about the language output of LLMs. He is reasonably impressed. He describes the sentence structure and the prose style as “sound”. And that’s what struck me most. His praise for AI is faint. And, if you have any kind of creative ambition at all, that’s a damning critique.

Anyway, now you can aim off for my ignorance and prejudice.

Working

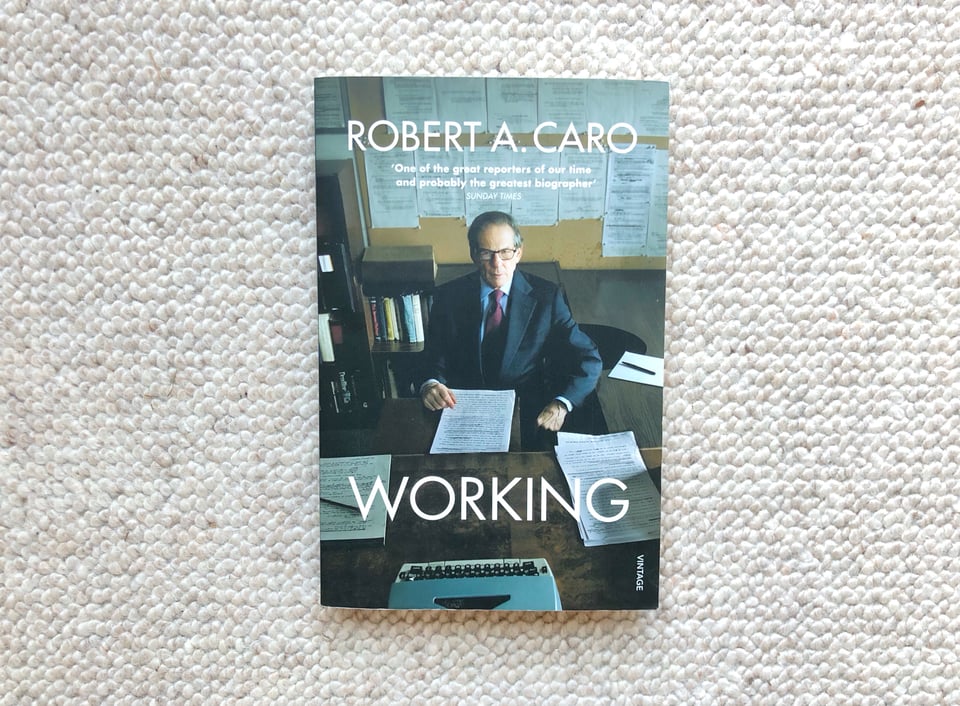

I was always going to love Working by Robert A. Caro.

Caro is the Pulitzer-winning journalist who’s most famous for his multi-volume biography of President Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ).

In this book - the clue’s in the title - he shares his approach to doing the work of a reporter, biographer, and nonfiction writer. He shares some of his experiences and some of his tricks of the trade.

No way would this man allow any kind of AI anywhere near his work. He doesn’t even use a computer. He writes his drafts longhand - pen to paper - until he’s happy enough to transcribe them on an electric typewriter.

Caro has hit home run after home run by doing the work. He spends years following his nose through boxes and boxes of dusty archive material. And he talks to people; lots of people, often talking to the same person several times.

Caro has this radical approach of thinking things through before he writes anything down. In his early days he was too keen to write, and writing came so easily to him that he’d do it fast, without having to think too hard about the words he was typing. A professor on the Princeton creative writing course saw through Caro and warned against “thinking with your fingers.” Caro took this advice to heart and lived by it thereafter. Drafting with a pen is a deliberate device to slow things down and ensure that he thinks with his brain. It seems to me that today’s AI efficiency shortcuts are the contemporary equivalent of thinking with your fingers. Slow down. Do the work.

Sourcing

Caro does painstaking research, getting as close to his sources as possible. People remark on how long he’s taken over each of his volumes - many years for each. Most of this time is spent on research and thinking things through rather than writing.

Caro interviewed people in the hill country of Texas where Johnson grew up in order to learn about the environment in which the young LBJ had his formative experiences. But many sources were reluctant to open up to an outsider. So Caro and his wife sold up and moved there for three years. The trust he earned from this gesture prompted people to share revelations that were the making of his first volume, setting Caro’s work apart from all previous writing about President Johnson.

Caro refers to his sources as witnesses. It’s a much better word than stakeholders, a word I use a lot but always with a twinge of regret. Maybe I’ll talk about witnesses from now on. Truthful testimony, freely given from a place of hard-won trust, is a precious thing.

Scenting

Another formative piece of advice, given to Caro as an enthusiastic but green reporter at Newsday by its Managing Editor, Alan Hathway, was to “Turn every page. Never assume anything. Turn every goddamned page.” Good advice, no doubt, but what do you do when the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum in Austin Texas contains 32 million pages of archive material? If you’re Robert A. Caro, you follow your nose until you pick up the scent of something important, and then you follow the scent doggedly, turning every page of every document on the trail until you find the buried treasure. Here’s how Caro describes one such episode. It’s the first of a couple of long extracts from the book, but they’re both worth it.

Obviously we couldn't turn every page, or even a substantial percentage of them. But I knew we had to turn as many as possible. And we turned quite a few, requesting a lot of boxes, looking through a lot of file folders that, from their description in the Finding Aids, one would assume contained nothing of use to me - and the wisdom of Alan's advice was proven to me again and again. Someday, I hope to leave behind me a record of at least a few of the scores and scores of times that that happened, some of which may be of interest, at any rate to fellow historians; for now, I'll give just one example. I had decided that among the boxes in which I would at least glance at every piece of paper would be the ones in Johnson's general "House Papers" that contained the files from his first years in Congress, since I wanted to be able to paint a picture of what he had been like as a young congressman. I thought that by doing that I could also give some insight into the life of junior congressmen in general. And as I was doing this - reading or at least glancing at every letter and memo, turning every page - I began to get a feeling something in those early years had changed. For some time after his arrival in Congress, following a special election in May 1937, his letters to committee chairmen, to senior congressmen in general, had been in a tone befitting a new congressman with no seniority or power, in the tone of a junior addressing a senior, beseeching a favour, or asking, perhaps, for a few minutes of his time to discuss something. But there were also letters and memos in the same boxes from senior congressmen in which they were doing the beseeching, asking for a few minutes of his time. What was the reason for the change? Was there a particular time at which it had occurred? Going back over my notes for all the documents, I put them into chronological order, and when I did it was easy to see that there had indeed been such a time: a single month, October 1940. Before that month, Lyndon Johnson had been invariably, in his correspondence, the junior to the senior. After that month, and, it became clearer and clearer as I put more and more documents into date order, after a single date - November 5, 1940; Election Day, 1940 - the tone was frequently the opposite. And, in fact, after that date, Johnson's files also contained letters written to him by middle-level congressmen, and by other congressmen as junior as he, in a supplicating tone, whereas there had been no such letters - not a single one that I could find - before that date. Obviously the change had had something to do with the election. But what?

Robert A. Caro, Working (Researching, Interviewing, Writing)

Armed with this hard-won insight from his archive research, Caro could target appropriate witnesses with some very pointed questions. Caro endured the agony to get the epiphany. This is sacred human work. AI might do a good summary but it’s not going to find and follow a scent like this.

Asking

My two most recent posts have both been about asking good questions. One of Caro’s favourite questions is, “What did you see?” Caro believes that a vital skill for any nonfiction writer is to create a sense of the places in which historical events take place. He doesn’t just want his reader to know what happened, he wants them to know what it felt like to be there. Eyewitness testimony is obviously vital for this work. And, “What did you see?”, asked relentlessly until he gets a satisfactory answer, is Caro’s go-to gambit.

Interviewing: if you talk to people long enough, if you talk to them enough times, you find out things from them that maybe they didn't even realise they knew. Take the evening of March 15, 1965. Johnson is going to address a joint session of Congress and he comes out of the White House and gets into the backseat of the limousine for his ride to Capitol Hill. Three of his assistants, Richard Goodwin, Horace Busby and Jack Valenti, were sitting on the limousine's jump seats facing him. I never got to talk to Jack Valenti about that ride, but I talked to Goodwin and Busby, and I also interviewed George Reedy, who talked to all three of them the next day, and I asked Reedy what they had told him. I kept asking Goodwin and Busby, What was the ride like? "What did you see? What did you see?" My interviewees sometimes get quite annoyed with me because I keep asking them "What did you see?" "If I was standing beside you at the time, what would I have seen?" I've had people get really angry at me. But if you ask it often enough, sometimes you make them see. So finally Busby said, “Well, you know, Lyndon Johnson was really big. And sitting on that backseat, the reading light was behind him, so he was mostly in shadow, and somehow that made him seem even bigger. And it made those huge ears of his even bigger. And his face was mostly in shadows. You saw that big nose and that big jutting jaw.” I didn't stop. "Come on Buzz, what did you see?" And finally he said, "Well, you know - his hands. His hands were huge, big, mottled things. He had the looseleaf notebook with the speech open on his lap, so you saw those big hands turning the pages. And he was concentrating so fiercely. He never looked up on that whole ride. A hand would snatch at the next page while he was reading the one before it. What you saw - what I remember most about that ride - were the hands. And the fierceness of his concentration - that just filled the car." So thanks, Buzz. Now I had more of a feeling of what that ride was like.

Robert A. Caro, Working (Researching, Interviewing, Writing)

I’m no Robert Caro but I do something similar in my stakeholder (witness) interviews. I’ll effectively ask the same question several times, but with enough variation in the wording for it not to feel repetitive. It happens time and again that one particular variation on a question will draw out a revelation where all other angles of attack have drawn a blank. I’ll be none the wiser as to why that angle worked, but I’ll have what I need, so who cares? I guess it’s like fly fishing (which I’ve never done) in that you try different flies and keep casting in the same place until you get a bite. The risk of irritating a witness with semi-repetitive questions is far outweighed by the reward of them handing you the key to a project on a plate.

Agonising

I didn’t mean this to be a post about AI. It started as a book review. But the book in question is about humans doing the work for which we’re uniquely qualified. It’s about doing the spade work that leads to creative output of high quality and enduring value. It’s about the agony that leads to epiphany. And I don’t - won’t - believe that efficiency leads to epiphany in the same way, if at all. Robert Caro’s book is the perfect affirmation of that stance.

I can't start writing a book until I've thought it through and can see it whole in my mind. So before I start writing, I boil the book down to three paragraphs, or two, or one - that's when it comes into view. That process might take weeks. And then I turn those paragraphs into an outline of the whole book… Getting that boiled-down paragraph or two is terribly hard, but I have to tell you that my experience is that if you get it, the whole next seven years is easier.

Robert A. Caro, Working (Researching, Interviewing, Writing)

Maybe try this too: After Which Everything Was Different - a post about several books that made me better at what I do.

Join the discussion:

-

"you’re not going to hit a home run either if you start from second base without knowing how you got there" - yes to all of this Phil. Very well put, and me too.

-

Reading this made me happy about working the way I do - and the other thing about “stakeholder”/witness interviews is that the interviewee also gets a sense of satisfaction and learning from speaking with another human being for 45 minutes or whatever it is.

I don’t really like the word “witness” for this, though - it has too many associations with crime and courts for me - there must be a better word than either stakeholder or witness ... (scratching my head) ...

-

I like “ the agony that leads to epiphany”, Phil. Keep on doggedly reading, reflecting and writing

Add a comment: