There's got to be a better way

Workshops, huh! What are they good for?

There are Two Tribes when it comes to workshops. Those who swear by them, and those who swear at them.

Judging by how many processes involve (or default to) workshops, I have to conclude that the swear-by tribe enjoys a significant majority. Indeed, in many cases, workshops are the process.

However, I’m most often in the latter camp. You, dear reader, should aim off for this bias if you stay with me beyond this paragraph. My sceptical attitude to workshops may come across as curmudgeonly, perhaps even blinkered. But it’s based on a career’s worth of empirical observation.

It doesn’t help that I’m not a natural facilitator. Even the most fun sessions with people I know well leave me utterly drained. The last thing I associate with workshops is being able to Relax. In fact, my first instinct tends to be Don’t Do It.

(No more Frankie Goes To Hollywood references hereafter.)

My biggest beef about workshops is that, often, they’re not the best method to achieve the desired outcome. But people do them anyway for some reason. In my four years of brand strategy consulting, there has always been a better way than a workshop.

Comprehensive or creative.

There are two types of workshop. One is productive. The other is counter-productive:

Type A: Many hands make light work.

Type B: Too many cooks spoil the broth.

Many hands make light work when the priorities are to be comprehensive and/or inclusive.

Too many cooks spoil the broth when the priority is to be creative.

Brand strategy, indeed any kind of strategy, is a creative endeavour. So, in my view, strategy workshops too easily end up as Type B. Problems arise when you cross the streams between Type A and Type B workshops. People try to use workshops for inclusive strategy or inclusive ideation, both of which are paradoxes.

The most successful workshops that I’ve facilitated, and the only one that I was truly proud of, were all Type A gigs.

Anatomy of a successful workshop.

What was so special about this particular workshop?

Our client had been tasked with standing up a brand new bank from scratch. We were building the website. Big job. The client product team moved into the agency for many months to work as one with our devs, designers, and UX bods.

The work was divided into significant but manageable sub-projects, and the objective of this workshop was to get the ball rolling on one of these. From memory, it was a new section of the website that was required to perform certain important functions. The goals of the workshop were to generate an exhaustive list of User Stories for this website section, and organise them into Epics.

Workshops are good for this kind of collective work - generating exhaustive lists; clustering and prioritising; auditing; committing. Many hands make light work when comprehensiveness and consensus are the objectives.

I wasn’t part of the project team. I was brought in to run this one-off workshop.

Before the workshop I had only a loose idea of what user stories were and what purpose they served. I wasn’t an expert but I assumed that everyone on the client team would be. They had to be, right? So, in preparation, I did some research to get a better grasp on the topic. And it quickly became apparent that there wasn’t a definitive approach. Opinion was divided on how to write a useful user story. There didn’t appear to be a gold standard that everyone worked to.

This made me wonder whether there was unanimity within the client team as to what a good user story looked like. It turned out there wasn’t.

So I organised a pre-workshop preparation meeting with all the attendees and moderated a discussion about user stories: what are they for; what happens when they’re done wrong; what doesn’t happen when they’re done wrong; what do they look like done right; what’s the appropriate relationship between user stories and epics; how will we evaluate user stories in the workshop?

It was fascinating. They were as surprised as me by the lack of consensus in their own team. They’d been taking a lot for granted. But, by the end of the meeting, we’d reached agreement on the structure and qualities of an ideal user story, and on a set of pass/fail evaluation criteria that we’d use in the workshop. Leaving the meeting, the general feeling was that the session would have lasting value beyond the forthcoming workshop, equipping the team to better tackle the entire project.

The preparation meeting had lasting value for me too. I’d got to know all of the workshop attendees. I’d established rapport. And I’d gone from being someone with zero expertise and zero authority in their eyes to someone who had identified an issue they didn’t know they had and helped them resolve it.

Understanding attendees is as important to planning a workshop as understanding an audience is to planning an advertising campaign.

On the day of the workshop I didn’t need an ice-breaker exercise because the ice had been broken in the preparatory session. So there was no risk of shooting myself in the foot with a cringeworthy, misjudged warm-up.

And we didn’t have to waste valuable workshop time debating objectives and ground rules before we got started. All that had been done in the preparatory meeting too. Any politics, posturing, and power-play within the team (there wasn’t much of any to be fair) had also been flushed out in the pre-meeting. In the workshop we just got down to business and battered through an awful lot of useful work, both in small teams and as a group. We generated. We reviewed. We organised.

We put many hands to good use and did valuable work. And a workshop had been the most appropriate format to get this work done. I knew that my management of the process had added real value. And the senior client sent me a thank you message that confirmed this.

On reflection, I’m more proud of the groundwork than I am of the workshop, which is the moral of the story.

Workshop exercises that land well with one group of people will die an excruciating death with another. Neither introvert me nor professional me can imagine anything worse than turning up to facilitate a workshop with people you’re meeting for the first time.

Dealing Directly (Access) is one of my values for consulting work and it applies as much to meeting workshop attendees in advance as it does to conducting primary research with my clients’ customers.

Great strategy isn’t done by committee.

I don’t use workshops for brand strategy work. Brand strategy is about codifying what makes my clients brilliant. I gather insight as my raw material. And I synthesise that insight into a simple, compelling, pragmatic brand blueprint.

A workshop wouldn’t be my first choice method for gathering stakeholder insight. I doubt it would be my second choice either. I much prefer one-on-one interviews. If I had to, I might reluctantly use a stakeholder workshop as a focus group in disguise. In rare circumstances I’d tolerate a workshop as an insight tool. But I won’t outsource the hard, creative synthesis work of brand strategy to a workshop.

I know some people do. The attraction of working with clients on strategy in a workshop is that they co-create and therefore co-own the output. However, from what I’ve seen, this comes at a high price. And that price is mediocrity. Brand strategy workshops churn out usual-suspect values and bland, comfortable positioning statements.

Workshops tend to be infertile and hostile environments for trailblazing ideas and original thought.

Occasionally the seed of a great idea will come out in a workshop. But, nine times out of ten, it will be killed by convention-bound groupthink. Workshops are stony ground for radical thinking. Workshops generate and impose structure on high quantities of information; they don’t originate high quality ideas.

As a rule: workshops are for prose not poetry.

I have witnessed two exceptions to this rule.

1. There is no other

At the 2016 Do Lectures, gentleman Lebanese chef, Kamal Mouzawak, ran a tabbouleh workshop. We sat at a long table, shaving parsley and finely chopping the other ingredients according to his instructions. As we worked, Kamal described the history, geography, and sociology of Lebanon, and how these factors are reflected in its food.

He painted a vivid picture of a land in which a complex variety of different peoples co-exist, but where there are no minorities, where there is no concept of “other”.

The ingredients of tabbouleh are finely chopped and, once mixed, the variety is plainly visible but the components are impossible to separate. It’s a dish of complexity and complementary flavours, in which no ingredient is “other’.

The tabbouleh we had made together was a metaphor for Lebanon. We had been participants in a brilliant piece of participatory storytelling. None of us saw the punchline coming. It was workshop genius. It was poetry.

There were about fifteen of us around the table, but there weren’t too many cooks, and we didn’t spoil the broth tabbouleh.

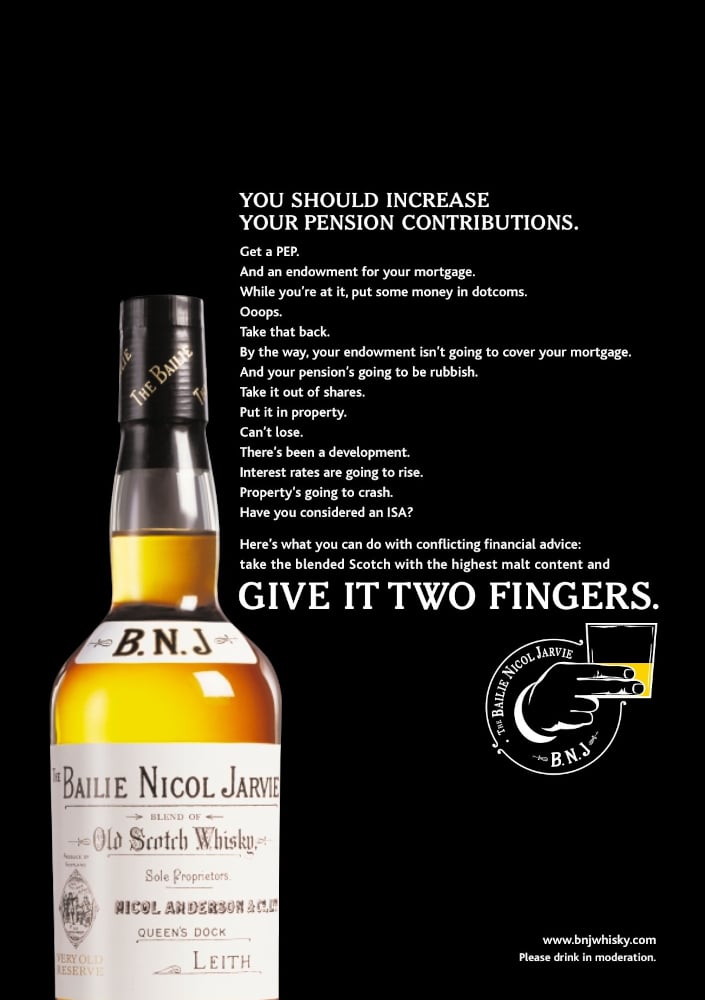

2. Give it two fingers

The second exception to the rule is the only time I’ve seen brand strategy done well - exceptionally well actually - in a workshop.

A whisky client decided to apply challenger theory to one of its brands. They hired Adam Morgan and his Eat Big Fish consultancy to work with the brand team and their agencies to develop a challenger positioning for the brand.

The process involved a series of workshop exercises over two (maybe three) days. And we ended up in a very good place, with a powerful positioning, which fed into a compelling creative brief, which led to powerful advertising.

There are several reasons why this process worked and most brand strategy workshops don’t.

The whole process was based on the premise of standing out. You don’t hire Eat Big Fish to find your inner challenger if you’re risk-averse, or if ‘good enough’ is good enough.

The workshop exercises were all based on aspects of challenger theory. They forced you to push the boundaries. Mediocrity had been designed out of the process.

There were people in the room whose job was to be creative, including our creative director. Everyone’s creative but some people are paid to be because they’re better at it. With properly creative people in the room, there were always good ideas to discuss. There was positive pressure on everyone to raise their game.

The quality control was excellent. The Eat Big Fish team were accomplished facilitators. They made it feel like all the best ideas had come from the group, but I observed them subtly nudging us away from the safe and towards the spiky throughout the process.

The extended process (days plural) allowed us to bond and develop a shared desire to do something special. More time created more space and more opportunities for everyone to shine. It stopped people feeling like they had to impress in every exercise. This meant that the best ideas were allowed to win in an environment where politics took a back seat.

If these conditions were easy to replicate I’d have a more favourable opinion of brand strategy workshops. But they’re not.

If a workshop has a creative objective, it should be populated by creative people; and I don’t mean “everyone’s creative” people.

But this creates a paradox. I strongly suspect that most people who are creative for a living would consider workshops an uncreative environment.

Also, professionally creative people often have a dogged, stubborn streak which can seem unreasonable on the receiving end. But they’ve learned the hard way that great ideas are fragile and don’t get made unless you fight for them. You won’t find doggedness, stubbornness, or being unreasonable in any workshop playbook. Necessary creative practice and best workshop practice are incompatible.

Everything I’ve witnessed in my career tells me that creative thinking, which includes strategy thinking, is best done in ones or twos. And it needs more than half a day.

If you’re after big ideas, don’t default to a workshop. There’s gonna be a better way.

Join the discussion:

-

Love this Phil. I attended a different workshop at the same edition of Do that focussed on making sourdough - again, the effect was an involved, participative story which engrossed and engaged the audiences.

Add a comment: