The night wanderings of an amorous cat

A wordy ramble

A ramble about words.

In the writing and in the editing I’ve tried to hold it back from becoming (too much of) a wordy rant. Words matter in the world of brands. We’re trying to create proprietary meaning for our clients that makes people want to buy from them. Proprietary language helps in this respect, but it requires effort and imagination. Effort and imagination are in short supply.

Diligent linguists

I’m reading “How I Escaped My Certain Fate” by the stand-up comedian Stewart Lee. It includes transcripts of three of his routines, which he has annotated to explain the thought process behind the stories and jokes.

Don’t ask, but there’s one story he tells at The Stand in Glasgow in 2005 that involves Guantanamo prison, a branch of Curry’s (electrical retailer) in Wolverhampton, and a woolly tea-cosy. This is one of his margin notes:

‘Wool’ is a brilliant, all-purpose funny word. Few things are not made funnier if one imagines them being made out of, or coated in, wool.

Stewart Lee, How I Escaped My Certain Fate

Later in the book, Lee calls out ‘coquettish’ for being innately funnier than alternative words. It reminded me of something James Acaster said on the In Writing podcast a few years ago.

Choosing your words is probably the most important thing when it comes to comedy writing, and maybe just writing in general. Just choosing phrases that are funnier.

James Acaster, In Writing podcast, 26th March 2021

Acaster describes one of his routines about why it’s a bad idea to make a nuisance of yourself in a restaurant. The kitchen staff have all the power when it comes to retaliation. The routine includes a section about Wahaca’s stolen spoon amnesty: bring back stolen spoons in January and get free tacos.

And I think the line I had in it was that it's a double win for Wahaca because they get the spoons back, and they get to watch the thief eat tacos, which I imagine have been interfered with beyond belief. And 'interfered with' was funnier than saying spat in or jizzed in or whatever.

James Acaster, In Writing podcast, 26th March 2021

He goes on to talk about how the audience already knows the ending to that story before he gets there, so the laugh is in the language rather than the punchline. ‘Interfered with’ leaves room for the audience’s imagination. Everyone will have their own idea of how they’d least like their food to be interfered with, like a gastronomic Room 101.

You can follow along as American comedian, Taylor Tomlinson, hones individual words and phrases for a new routine in this New York Times interactive story. She’s on the road, practising and pressure-testing the new routine to make it perfect for a Netflix special. As she goes she swaps out words and phrases, adds in little details, and learns where to add extra emphasis to get more laughs where there weren’t any, and louder laughs where there were. She chooses a single syllable name for her friend’s boyfriend (Todd) because ‘faster is funnier’. She changes ‘I was so horrified and touched,’ to ‘it was so sweet and so hurtful,’ and she’s rewarded when the next audience responds with higher intensity to the improved version.

Comedians obsess over individual words and phrases, and they test and learn, test and learn, test and learn, to wring the maximum comedic effect from their language. They’re good listeners. Their material only gets better, the impact only increases, if they read the room and make changes in response. They are diligent linguists.

Intellectual onanists

What if we were as diligent as comedians with the language of business? What extra effect could we wring from our words? Most business people will never know, for one of two main reasons.

Stand-up comedians want their material to be unique. They want proprietary laughs. So they put a lot of effort and imagination into their words. Many (most?) business people are the opposite. There’s a herd mentality in business, particularly when it comes to lingo. Personal identity is less important than fitting in. So the herd uses in-crowd words, even if they’re ridiculous (see ‘space’ and ‘revert’ below.) Herd language is thoughtless language.

For stand-up comedians, it’s all about how their words land with their audience. Nothing else matters. Their language is in service to the laughs. I’m sure they all have strong egos, but they don’t let their egos get in the way of words that work.

Sadly a lot of business-insider language comes down to posturing. It’s absolutely driven by ego. People use words that (they think) make them seem clever. They’re not concerned with how they land. Their use of language is self-serving.

Thoughtless and self-serving: in business you have a large crowd of idle linguists mimicking the words of a smaller bunch of intellectual onanists.

This is an open goal for businesses, brands, and people that choose their words carefully. Proprietary meaning that lands well is just as valuable for people as it is for brands, whether it’s a Tinder profile or a LinkedIn bio.

Words that work

In my last post, I wrote about the Australian data science firm, Hermit Tech. They refuse to talk about ‘bugs’ in their code. They call them ‘mistakes’ instead. Mistake is a loaded word. It’s loaded with accountability and integrity, which sets them apart from their competitors and breeds trust. They’ve chosen their words carefully and they’ve seen them land well with prospects.

You should read “Words That Work” by Dr. Frank Luntz. I’m no fan of his politics, but I’m a huge fan of his methods.

Luntz is a famous pollster, who’s done a lot of famous work for businesses and the Republican Party. He’s credited as the messaging mastermind behind concepts like ‘climate change’ (to replace ‘global warming’) and ‘death tax’ (to replace ‘estate tax’.)

His thinking is entirely informed by audience research. He conducts hundreds of interviews and focus groups, in which he tests and learns, tests and learns, tests and learns. Like a stand-up comedian, he learns the hard way that some words work better than others. His mantra is that, ‘It’s not what you say, it’s what people hear.’

You can have the best message in the world, but the person on the receiving end will always understand it through the prism of his or her own emotions, preconceptions, prejudices, and pre-existing beliefs. It's not enough to be correct or reasonable or even brilliant. The key to successful communication is to take the imaginative leap of stuffing yourself right into your listener’s shoes to know what they are thinking and feeling in the deepest recesses of their mind and heart. How that person perceives what you say is even more real, at least in a practical sense, than how you perceive yourself.

Dr. Frank Luntz, Words That Work

In the book, Luntz picks out 21 words and phrases for the 21st Century, based on his conversations with the vast American public.

For example, based on shifts in American sentiment and sensitivities, he identifies ‘peace of mind’ as a more resonant concept than ‘security’.

In the consumer realm he finds that ‘hassle-free’ has become far more appealing than ‘less expensive’.

And so on… Luntz is an expert in loaded words.

When I worked with Firstport (the first port of call for social entrepreneurs), I conducted interviews with social entrepreneurs, in which we explored how various words and phrases landed with this sensitive audience. Social Entrepreneurs, not surprisingly, are mainly concerned with the social impact of their ventures. ‘Profit’ can be a dirty word. But profit funds purpose. More profit means more impact, so profit is an idea that they need to come to terms with. They self-identify as social entrepreneurs, but ‘entrepreneur’ is also a heavily loaded and polarising word. By testing and learning in the style of comedians and pollsters, we came to understand how these words worked and how to use them.

“Words That Work” is an informative read if you’re interested in high-impact language and loaded words.

Words that don’t work

A lot of business language is decidedly unloaded. In most proposals, most decks, most pitches, most business people are firing blanks.

Passion is a blank word. Marketing people are fond of it. I associate passion with lazy sponsorship advertising: ‘We’re sponsoring this rugby tournament because we’re as passionate about rugby as you are.’ Aye, right. They can’t think of anything better to say. They haven’t tried to think of anything better to say.

Passion reeks. Passion is pungent, like Axe Dark Temptation body spray. Don’t tell me about your passion, give me a whiff of it instead.

Space is both literally and figuratively a blank word. The use of space in a vain attempt to signify business acumen seemed to explode around the turn of the century.

“So, yah, like, we’re going for first-mover advantage to monetise the SaaS space, right?”

“Speak to Steph. She knows what’s kinda really going on in the enterprise space.”

Used like this, what space actually signifies is someone with pseudo tendencies who likes the sound of their own voice. Every time - and I mean every, single, time - I’ve heard someone say ‘space’ instead of ‘market’ or ‘industry,’ they’ve said it in a posturing way for self-aggrandising effect.

So, if I inadvertently called you a pseud and a poseur just then, I’m only half sorry because you’d first have to self-identify as a space-saying pseudoposeur in order to be offended. So who’s really at fault there?

People love to talk about new paradigms. I don’t have a problem with that per se, as long as what they’re describing fits the bill. Mostly it doesn’t. Mostly it’s ridiculous hyperbole; worse actually, it’s pseudo-intellectual hyperbole. I suspect that people just like the sound of the word as it leaves their lips. Paradigm is (usually) a blank word, but it has a good mouth-feel.

All mouth-feel and no flavour

My beer clients used to obsess over mouth-feel when they were doing new product development. Beer can be enjoyed for its body and texture as well as its flavour. The whole industry worked itself into a froth (or was it a lather?) over nitrogen kegs. Nitrogen creates a richer, smoother mouth-feel than carbonation. Creamy beers like Boddington’s and Caffrey’s really were a new paradigm for ale drinkers. So much so that nearly everyone who worked on them claimed to have invented them.

As an ale drinker myself I always thought that these paradigm-shifting beers had traded flavour for texture. What they’d gained in body they’d lost in substance. And I feel the same way about words like paradigm and monetise. They’re great to roll your tongue around, but they don’t satisfy.

I’m reminded of the Monty Python sketch about woody and tinny words. Woody words like sausage and intercourse have a pleasing mouth-feel. Tit, by contrast, is unbearably tinny.

I doubt that we’d hear words like synergy and ecosystem so much if they weren’t so pleasurable to say.

Metaphors and syllables

I never say ecosystem. Sometimes it’s an accurate metaphor for the industry or structure it’s describing. But, I dunno, it feels lazy to me even if it’s right. Accuracy and appropriateness on their own don’t justify the use of a metaphor.

If you use metaphor, it has to be good. No, it has to be perfect. Just as there is nothing so awe-inspiring as a metaphor that sparks the imagination, there is nothing so dispiriting as an inept one - or hopeless cliche. Let the metaphor maker beware... Metaphors must be original, invented by the writer for the story at hand. A metaphor has the shelf life of a fresh vegetable.

Constance Hale, Sin and Syntax

The pleasing mouth-feel of business language seems to equate to syllables. Polysyllabic words like paradigm and ecosystem and synergy (and polysyllabic) make you feel clever. The problem is that they don’t make you sound clever. This has been scientifically proven. Professor Daniel Oppenheimer concluded from his research that people associate intelligence with clarity of expression. You’re trying to talk yourself up when you use long words, but I’m marking you down.

Back in 2017 I wrote a love letter to the lyrics of My Girl by Madness.

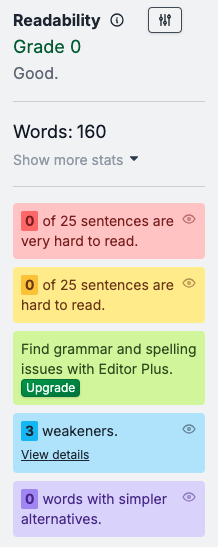

I pasted the lyrics into the Hemingway Editor, which uses various conventions to posthumously cast the author’s brutal eye over your text. My Girl gets the best score possible. Although, in typical Hemingway fashion, it understatedly describes the result as “good”.

It’s actually better than good. One of the three “weakeners” identified by the app is the use of the passive voice in the line, “I tried and tried but I could not be heard,” which completely misses the point because it’s a deliberate device to create a rhyme with the previous line, “We hardly said a word.” (AI is shit with creativity, ha!)

My Girl is a masterclass in the potency of short words and elegant, economic language. 140 of its 160 words are single syllables. There are 15 two-syllable words and 5 three-syllable words. The three-syllable words are telephone, everything, understand, realise, and unaware. There’s nothing pseudo-intellectual about it. It’s prosaic and profound. It’s profound because it’s prosaic.

There’s this wonderful short video of Mike Barson, who wrote My Girl, wandering around Crouch End in a pork-pie hat, remembering the relationship he wrote about in the My Girl lyrics. It’s so him. He’s Mister Deadpan. Meet my friend, Mr Deadpan Down-To-Earth. “I used to deliver bananas when I wrote My Girl.”

“His girl” was Kersten Rodgers and she appears in the video, giving her side of the story. His girl was indeed mad at him at the time, justifiably so. Hardly saying a word is just his nature, except when he’s writing songs.

They can both laugh about it now.

Fancy words = flimsy language

I apologise for pivoting into a Madness detour. I felt the need to flex that idea. I’m going to loop back now. I’m going to revert back to the subject of words in business.

Loop, flex, pivot, revert: these words have invaded working life like a knotweed.

I hate pivot. There has been a pivot pandemic. Pivot has an R number (remember those?) much greater than 1. Every meeting, every email, every pitch deck is a pivot superspreader event. And the business community is incapable of developing herd immunity to clever-sounding words. So now we’re all movers and shakers in the pivot space, yah?

I hate pivot but I particularly loathe revert.

“We’ll put our heads together and revert back to you on Monday.”

I loathe revert and I loathe that ‘back’ is superfluous in the context of revert. It’s a tautology. When people use words like ecosystem to sound clever, at least it’s effortless. But to say ‘revert back’ rather than ‘get back’ is so obviously wrong that it requires hard work. We can all see what you’re trying to do.

I can only read a sentence like the one above using a Bob Mortimer, Train Guy voice.

These words - revert, pivot, monetise, flex - are more lingo than jargon, but people use them for jargonesque effect, to signal insider status. All I can say is they send a different signal to me.

Fancy words make for flimsy language if you use the wrong ones.

Grandeur and style

I’m not against fancy words per se. (I wrote about intellectual onanists a few paragraphs up.) I am against a lack of judgement or imagination. Style is important. And language with a hint of grandeur is vital to developing style.

Hermogenes realised that a speech that is extremely clear runs the risk of appearing to be trite, commonplace, or obvious. In his discussion of Grandeur (megathos) he therefore deals with the various ways in which an orator can keep the clear from appearing to be mundane.

Hermogenes’ ‘On Types of Style’ translated by Cecil W. Wooten

‘Onanist’ is the verbal equivalent of a depth-charge. It only explodes once it has sunk in. For some people it will only explode when they look it up. And I did that on purpose.

I use Lowfalutin to describe my own style because it’s actually highfalutin language. It’s a pretentious way of saying unpretentious. It’s a joke. It’s a loaded joke. It uses grandeur to say that I keep things simple in a more memorable way than saying ‘I keep things simple.’ And it has been tried and tested. People who get it get me, and we get along just swell. It’s a chemistry thing. A filter.

I did some work for a company that makes software for small travel businesses. Both my client and their clients are fighting the good fight against the faceless booking engines that dominate the industry. In that respect, they’re in it together even though there’s a buyer/vendor relationship between them. Having interviewed several of my client’s clients, it became apparent that one of my client’s values was ‘solidarity’. That isn’t their whole irresistible truth, but it’s a big part of it. Solidarity has grandeur. It’s a woody word. And it works hard in this context.

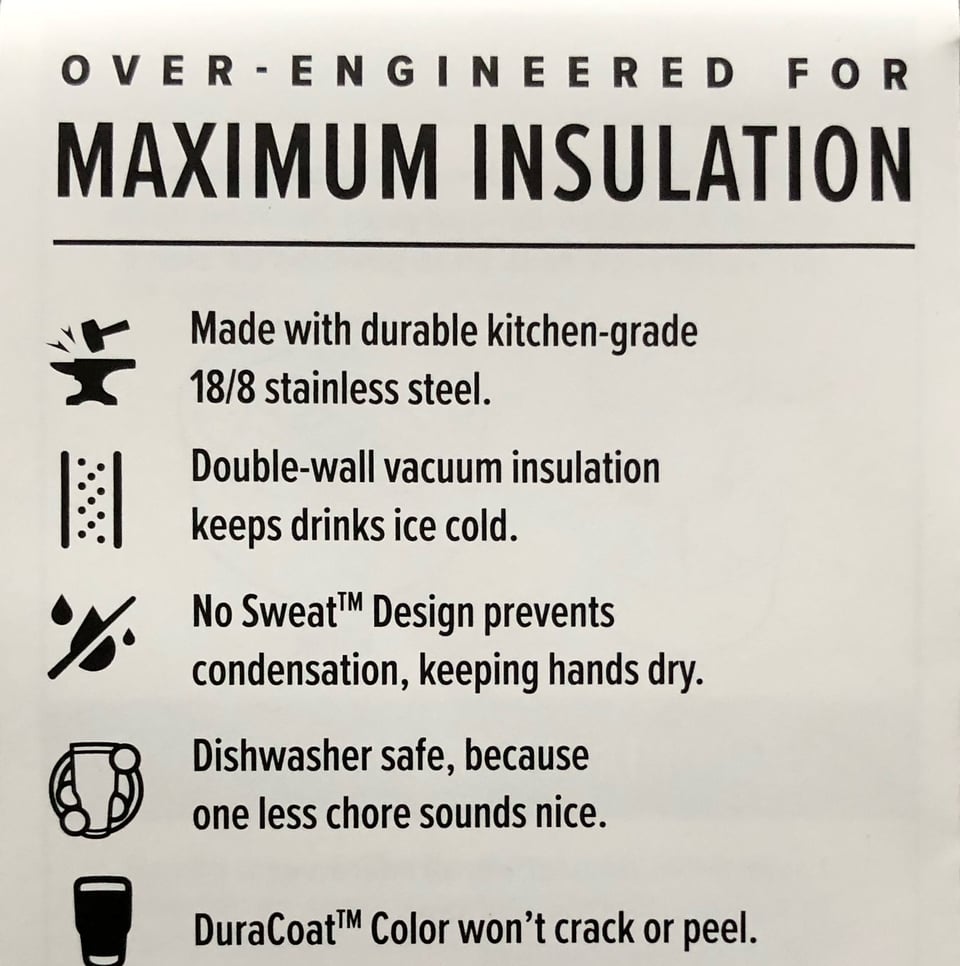

I own more Yeti products than I need, but I’m a sucker for utility. Yeti had me at ‘over-engineered.’ Over-engineered is a word that works. It’s proprietary meaning for Yeti that pushes the right buttons for me.

I’m dabbling with the idea of ‘romance’ for a project I’m working on at the moment. The industry has nothing to do with sex or dating. In my client’s context, romance could be a big, fat, loaded, and hard-working idea. We haven’t decided yet. It hasn’t been tried and tested. But we’re looking for proprietary words that work.

As with most things, it’s all about context and, as every comedian knows, it’s about being choosy with your words.

And so we’re back to where we came in.

The night wanderings of an amorous cat

Let’s bring this wordy ramble to an end with some wordy love to balance the wordy loathing.

I love etymology. And when you find that the word ramble is at least partly derived from the middle Dutch word, ‘rammen,’ meaning ‘to copulate,’ in the manner of the ‘the night wanderings of an amorous cat,’ what’s not to love?

Maybe try this too: Mixtaping my metaphors

Add a comment: