Thank you for your hard work

A post about belonging.

The smell of resignation

A long, long time ago I was on the BBH team that pitched for the Hoover advertising account. BBH had a penchant for jaded brands that it could restore to former glory, and Hoover fitted that bill nicely.

With Messrs Bartle and Hegarty and others I made the trip over to Hoover’s head office in Merthyr Tydfil in South Wales. The offices were attached to Hoover’s main white goods factory, which was churning out washing machines and tumble dryers in ever decreasing numbers. I like an office that’s part of a factory, where marketing and manufacturing get to mingle. People in business attire sit next to people in hard hats or hair nets in the canteen. And you can deduce a lot about the culture by watching how the people in different outfits behave around each other.

Hoover’s offices were as tired as the brand. And the atmosphere in the corridors was about as jolly as a cancer ward. You didn’t want to hang around too long, lest the smell of resignation should impregnate your clothes. The factory had long been the lifeblood of the town, employing thousands of people at one time, but the pitch had been called in response to falling sales. They were making heavy layoffs.

We lost the pitch in the end, but it wasn’t devastating in the way that losing a pitch can be. Winning was less attractive after our time in Merthyr. My abiding memory is walking up the stairs from the marketing department and nearly tripping over the comically deep pile of the plush carpet as we entered the executive floor. The contrast with the shabby neglect of the offices below couldn’t have been more stark. The executive suite was smart, hushed, rarefied. It was an ivory tower made of walnut and Axminster. Hoover was cutting everything back except the luxury and privilege of the people doing the cutting. And they didn’t seem to care. I remember John Bartle’s anger at their arrogance and hypocrisy on the train back to London. The brazen disdain of Hoover’s leaders for the plight of their shop-floor colleagues smacked of corporate apartheid.

All us and no them

Hoover’s culture as I observed it was defined by us-and-them distinctions. It was deliberately, explicitly divisive.

But what if belonging was one of your KPIs? What if you were judged as a leader on your ability to create a shared sense of purpose in your team? What if your reward were partially tied to maximising the “us” and minimising the “them” feelings in your team?

I’m working with a client where this is the case. They run an annual survey, conducted by an external research company, that uses both direct and oblique questions to put numbers against things like belonging and the extent to which the company mission and values are known, understood, and practised.

Part of my brand strategy work has been to make the mission and values more relevant, credible, and usable as part of daily working life.

So I’ve been thinking about belonging a lot. And, as is often the case when you ponder a topic, some weird and wonderful reference materials have fallen serendipitously into my lap. Now they’re falling into yours…

Thank you for your hard work

I mentioned to James that I’m planning a trip to Japan in the Autumn. He sent me the link to the Abroad in Japan YouTube channel, which he’d watched to research his visit a few years ago. As I browsed a few playlists, I found the video below, about “essential” phrases.

For “essential,” read “esoteric but interesting”. The second of the three phrases is beyond my skills of pronunciation but I love its sentiment:

Here’s what the video’s presenter, an English teacher living in Japan, has to say about the phrase:

It literally means, 'You must be tired.' But it has the translation, 'Thank you for your hard work.' What I like about the word is that it encompasses Japanese culture in one word. You use it with everyone. Strangers on the phone you speak to at the end of the day on the other side of the country, you say, 'Thank you for your hard work.' It's acknowledging that everyone is playing their part. Everyone's playing their part in a bigger picture. Everyone's contributing towards society.

“Otsukaresamadesu,” is an all-us-and-no-them word. It literally embeds a sense of belonging and shared purpose into everyday discourse. Whether it’s a throwaway remark or said with feeling, it’s a constant reminder that in this country we’re all in it together. Lovely.

All they have is a job

Talking of lovely, I managed to snag a copy of Leap Before You Look, Michael Wolff’s coffee table book about his life in design.

Lovely undersells it. It’s gorgeous, beautiful, clearly a labour of love. It’s full of great stories and timeless wisdom, mainly from his days at Wolff Olins. And he talks about branding in my kind of lowfalutin language.

Wolff practised brand strategy as an upstream discipline. For him, branding is inseparable from business strategy when it’s done right. And it can only be done right if you get to work with the right calibre of brand leader. Wolff lionises the great clients behind his great work.

When brand strategy is business strategy, there is so much more to branding than visual design. Wolff talks about the importance of leadership, culture, and the role of people in building a brand. He talks about the importance of shared purpose and belonging.

People who work for a brand, particularly those who touch customers, have to believe in the brand's reason to be. If they don't respect the authenticity of the brand's underpinning idea, then all they have is a job. If you want your people to serve your customers, you have to serve your people. If you want your people to ensure that customers feel good, you have to ensure your people feel good. Why be in business if you don't believe in what you're selling? Why would you expect people who work for you and help building your brand to put their enthusiasm into delighting customers, unless they believe in it? They need to feel your enthusiasm for delighting your customers too.

Michael Wolff, Leap Before You Look

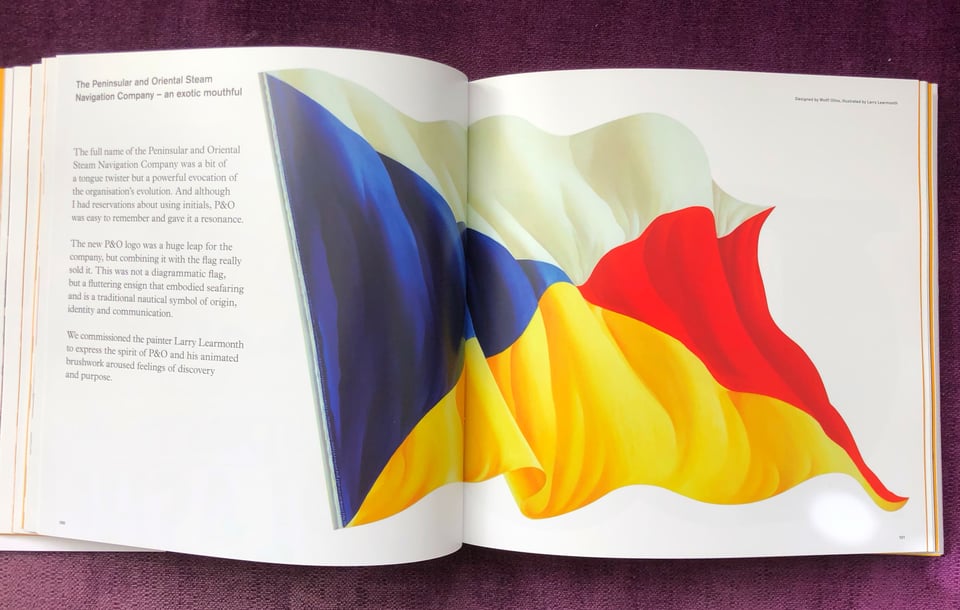

The whole idea of purpose has been much maligned of late, deservedly so when purpose is divorced from day-to-day commercial reality. But, throughout his book, Wolff gives example after example of service brands whose purpose is exactly what their customers are buying, and exactly what their people belong to.

Camden Council: connecting on the level with residents.

Bovis engineering: radical transparency in contracts.

Thorp model makers: attention to detail.

BFG (German bank): the rigour of banking with a human touch.

British Airports: cheerful competence.

Citizens Advice: empathetic conversations in sympathetic places.

3i: the creative use of money.

The Labour Party (Neil Kinnock era): a force for social change.

Paperchase: a love of all things paper.

Work at these organisations was more than just a job. They show that you can be part of something that’s noble and worthwhile as well as commercially successful. Everyone touched by the brand, including you, can be enriched by your endeavours.

Or you can work without purpose and, like Hoover, just suck it up.

Maybe try this too: Clutter is character. One of the stories in Michael Wolff’s book is about advising Tate & Lyle not to change the design of its Golden Syrup tin. If you read this, you’ll see that I agree with him.

-

Loved the reflections - brand, belonging and Japan! Tight up my street. Took me back to my time in Kanazawa- I spent 3 months working in the advertising dept of an electronics factory - who knew! I used to have to bow to the boss each time I needed to ask to go to the loo. And yes - we said those magic words Otsukaresamadesu every day. Sounded like abracadabra!

-

Thank you Phil. From now on, I’m going to be an antidisaugmentarian too!

Add a comment: