Strategy as a foreign language

A winning pitch makes sense. It makes sense to, and it makes sense of.

A winning pitch makes sense to its audience. They get it. More importantly, a winning pitch makes sense of their world. It gets them. It gets them to a better place: problem solved, achievement unlocked.

Making sense to is table stakes. Making sense of is the jackpot.

It’s that old thing about people remembering how you made them feel, not what you said. If a potential client leaves a pitch feeling that suddenly everything makes sense, that the ambiguity is gone and that opportunity is knocking, you’ve probably won.

We’re in the business of sense making.

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve quoted George Bernard Shaw to clients, colleagues, and myself. It’s the closest thing I have to a professional mantra.

The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.

George Bernard Shaw

Will they get it? Will they get it? Will they get it?

Have they got it? Have they got it? Have they got it?

The most important skill for communication professionals isn’t storytelling, it’s empathy. What’s it like in their shoes on the receiving end of your ads, your talk, or your pitch.

International English

A pivotal moment for me was when a little agency from Edinburgh won a pitch in the advertising equivalent of the Champions League to launch a new Honda car across Europe.

The glory of the win was gratifying but short-lived. But what I learned from the process has stayed with me, served me, and probably saved me on more than a few occasions.

We pitched for the pan-European launch of the new Honda HR-V. The pitch brief specified that the advertising should run in ‘International English’ in every market, with no adaptation into local languages.

This would be Honda’s first pan-European launch campaign. The European operating companies had been instructed by Japan to achieve more with less. The usual model of a separate launch campaign for each market fell victim to this edict. The requirement for International English was another cost-efficiency measure.

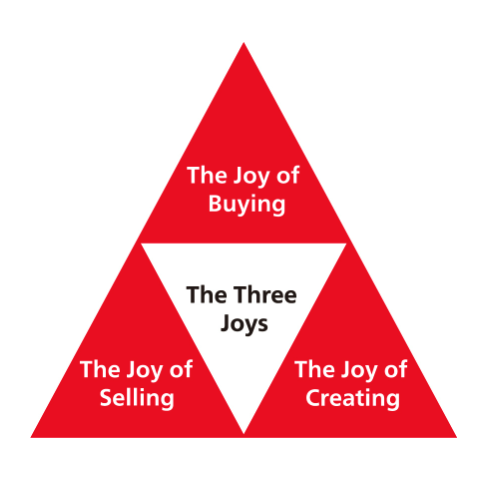

We won the pitch with our idea that christened the car ‘Joy Machine’. It’s a clunky phrase to British ears, but it worked well on the Continent. The idea was inspired by an aspect of Honda’s Fundamental Beliefs, called The Three Joys.

We had to deliver our pitch in International English too. The audience was made up of Honda marketing people from Germany, France, Spain and Italy, as well as the UK. There were several Japanese observers/influencers as well. For most of these people English was, at best, their second language.

When second language becomes second nature

We were given half an hour, tops, to present our strategy and our campaign. Language was a constraint and time was a constraint too.

In response, we cut the presentation team down to two: Gerry, our creative director, and me. In fact the whole thing was an exercise in cutting down and cutting out. It’s natural to be protective of funny asides and clever embellishments. You want to be smart and amusing in a presentation. But once we got into full-on declutter mode, the brutality was infectious. And effective. No preamble. No breaking them in gently. No interesting asides or tangents. The time constraint and the language barriers had a liberating effect.

We cut and cut until all that was left was essential context and content. What were our killer points, and what set-up did those points need to land effectively? Short straight lines between insight, strategy, and idea.

We cut out colloquial language and idioms.

We hacked the syllable count back to as close to monosyllabic as possible.

We interrogated every word and every sequence of words from the audience’s perspective to make sure that communication wouldn’t be an illusion.

And we rehearsed and rehearsed so that it was a comfortable thirty minutes to deliver. We rehearsed at about 80% of our normal delivery speed, which felt agonisingly slow to us, but which would be a kindness to the audience. Thirty minutes isn’t long for a pitch, but our presentation had room to breathe, which would aid its digestion.

Obstacles to understanding

Without knowing it at the time (obviously) we’d been following advice that the BBC journalist Ros Atkins would give many years later in his book, The Art of Explanation, which is summarised by Atkins in this handy Twitter thread.

Talking about simplicity, he quotes another journalist, Alan Little, who said, ‘Simplicity is the key to understanding. Short words in short sentences present the listener or reader with the fewest obstacles to comprehension.’ Atkins repurposed this idea as ‘obstacles to understanding.’

Before, when I thought about simplicity, I saw over-complication as a stylistic issue - something I wasn't keen on but could live with... I was now seeing these unnecessary details as a direct threat to what I was actually trying to do.

Ros Atkins, The Art of Explanation

Oh Lord, please don’t let us be misunderstood

We pitched in a sterile, airless meeting room in the Schiphol Hilton. Our punchy style was designed for effective communication, but it also helped to create a much-needed mood of vibrancy. One of the scripts had the HR-V driving over giant bubble wrap. Gerry handed out bubble wrap for the audience to pop so that they could experience the simple joy he was describing in the script.

Gerry watched the audience as I was presenting, and vice versa. They weren’t giving much away but there were nods in the right places (the Venn Diagram I used to summarise the strategy) and laughs in the right places (mainly the TV scripts). More importantly, we both agreed in our post-mortem that they’d all stayed with us throughout. We hadn’t lost them for a second. We’d definitely made sense to.

It seems that we made sense of too. Officially it was the Joy Machine campaign wot won it. But I’m sure that the work we put into sense-making paid off handsomely. I bet the other agencies didn’t put as much effort into being understood as we had.

The heading for this section is an amended lyric from the song, Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood. It was originally recorded by Nina Simone, but was famously covered by The Animals. The track appeared on the B Side of an EP released by The Animals in 1965. The first track on the A side was Boom Boom. How apt. Boom Boom is exactly the effect we’d been hoping for by ensuring that we weren’t misunderstood.

The Joy Machine ads ran in 1999/2000. Sadly I can’t find any trace of them on the Internet. They weren’t the best ads I ever had a hand in but their playfulness was ahead of its time for car advertising. It was mimicked by several brands, particularly BMW, in the following years.

No fuzz

Strategy and creativity are prone to fuzzy words, especially when they’re described by people whose primary objective is to look clever rather than communicate. There are a lot of those people in advertising, which is both ironic and bizarre when you think about the job they’re in.

I’m sure I was one of those people when I was younger. But in the words of Danny Glover in Lethal Weapon, ‘I’m too old for this shit’ now.

I’ve been too old for that shit ever since the Honda pitch actually. It was a great lesson that I return to every time. Imagine you’re presenting in someone’s second language. Eliminate the fuzzy words. Use high-resolution language to convey meaning in high fidelity. Identify and remove the obstacles to understanding.

I’ll end by quoting Ros Atkins again, in which he describes how this kind of simplicity is a double-whammy recipe for success.

Explanation is relevant whatever you're making the case for. It not only improves how you promote an idea, a request or a point of view - it will also improve the very thing you're promoting as well. In turn, if what you're promoting and how you're promoting it both improve, the chances of a desirable outcome increase.

Ros Atkins, The Art of Explanation

Join the discussion:

-

I also learned this lesson in the 1990s when I moved to Germany. There’s a place for clever English word-play, in-jokes and obscure UK cultural references - but it’s not when you’re pitching for and developing an international campaign. It doesn’t mean you can’t have fun with it, but it’s a different sort of challenge.

Add a comment: