Pubs, postage, and propaganda

A post about the limited power of advertising and the immense power of wanting something really badly.

The propaganda school of advertising

I’ve only worked on one outright propaganda campaign.

Some will argue that all advertising is propaganda, and they have a point, up to a point. Propaganda shares its root with propagate (obviously). So, stripped of its cultural baggage, propaganda is simply the propagation of an idea. And that’s what advertising is (equally obvious).

But propaganda is defined by its cultural baggage as much as it is by its etymology. Propaganda is inherently political. Propaganda campaigns propagate political ideas, many of them dubious, most of them unsubstantiated.

I’ve only worked on one of those.

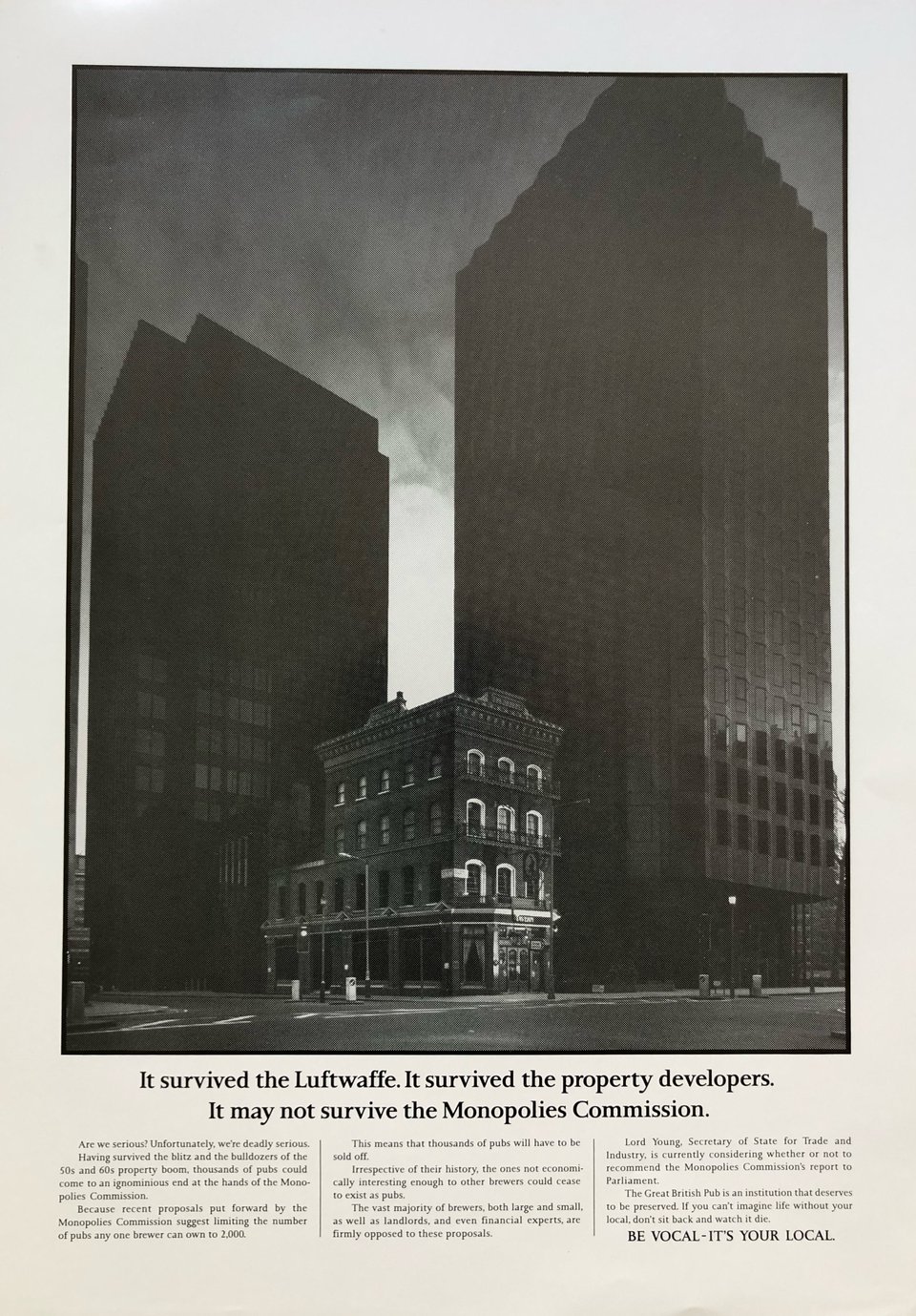

I found proof copies of these ads in a portfolio case at the back of a cupboard. 1989. Jeez. I was a whippersnapper suit, just out of graduate training at BBH.

The Brewers’ Society appointed BBH to run a campaign to fight the Monopolies Commission proposal to break the tie between the big brewers and their pub estates. The big brewers each owned thousands of pubs, through which they exclusively sold their own beers. This big-brewer domination of pubs made it difficult for small, independent brewers to secure on-trade distribution. In hindsight, it was a fair cop. If it looks like a monopoly, walks like a monopoly, and quacks like a monopoly…

The Brewers’ Society did what it said on the tin. It represented the interests of the brewing industry. And, when it came to the crunch, this meant the interests of the big brewers. They said society. You might have said gang; you might have said cartel.

BBH handled second string Whitbread brands like Moosehead at the time. This was before the famous campaigns for Boddingtons and Murphy’s, but we still qualified as a big-brewer agency. With its back to the wall, The Brewers’ Society appointed BBH without a pitch and threw money at us to kick up a stink on their behalf.

They claimed that breaking the tie would be bad for small brewers, resulting in the closure of many of Britain’s smaller, quainter, most treasured pubs.

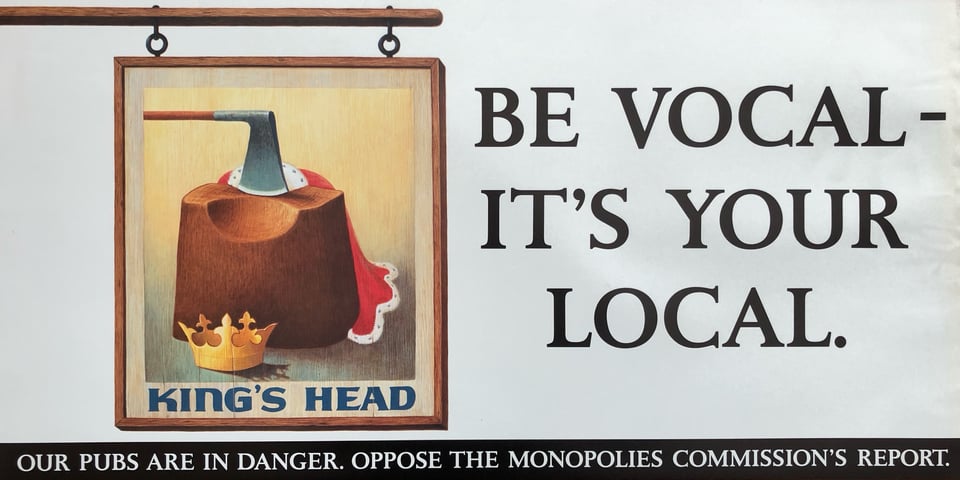

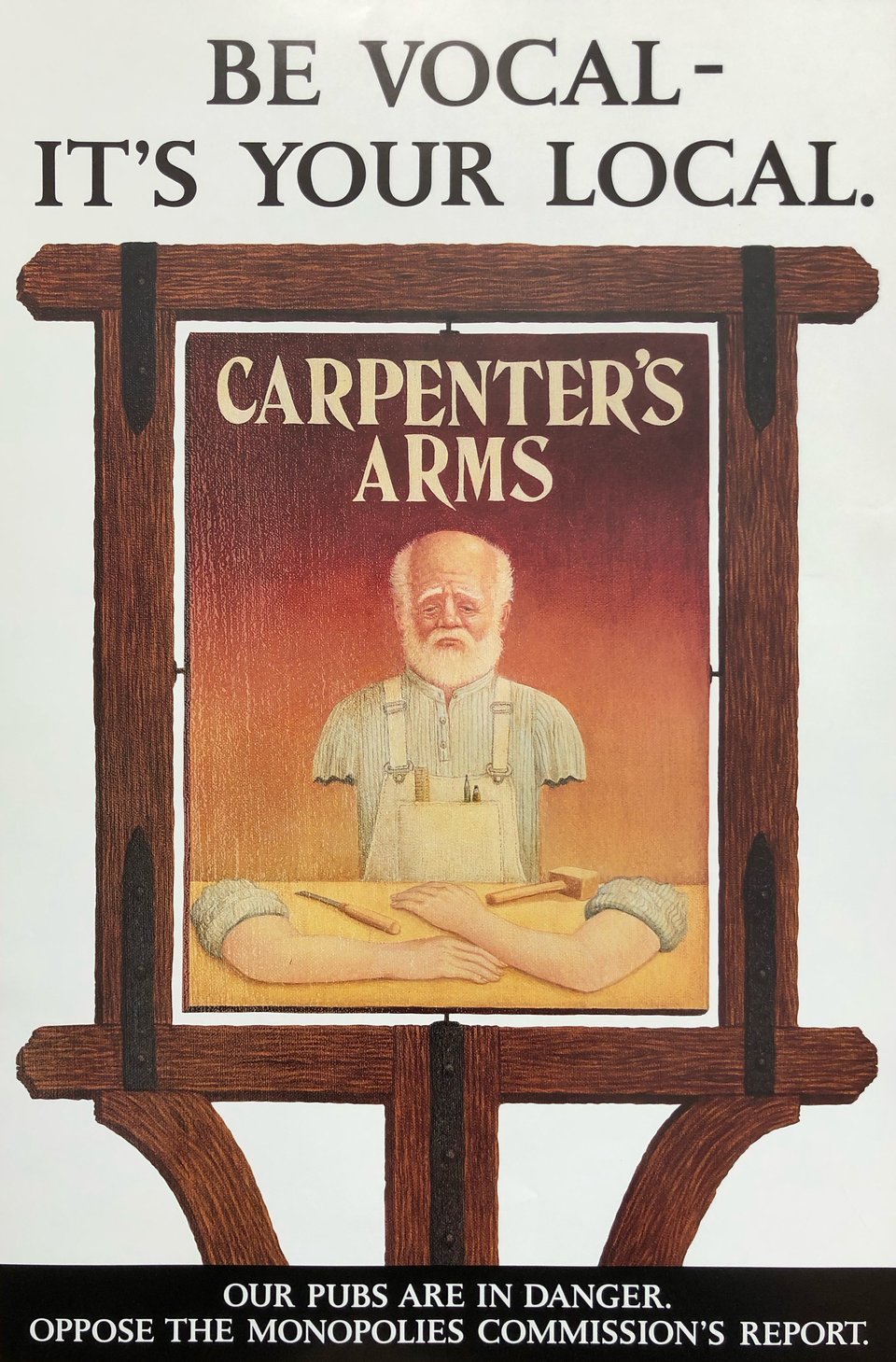

Hence: BE VOCAL - IT’S YOUR LOCAL.

This kind of sloganeering was very un-BBH. It feels more like a GGT idea, from the Dave Trott, ‘Ello Tosh, Got a Toshiba? school of advertising.

I had no input to the strategy. I was hardly even a bag carrier. It was Nigel Bogle’s account. He reverted to being a hands-on account manager for the duration, and I think he loved every second. But I got to tag along for the ride, and it was an education. To wit…

Lesson 1: Necessity and desire

Ad agencies excel at two things: having ideas and making ideas happen. The second skill is underrated, except by Saatchi & Saatchi, who celebrate it with their motto, “Nothing is impossible.” This makes Saatchi’s one of the few agencies that has an irresistible truth. It thinks bigger and acts bigger than everyone else. BBH used to be another when it referred to itself as a “Fame Factory,” which was a Nigel Bogle line incidentally.

Working in advertising teaches you that there are few things that can’t be done if you want them to happen badly enough. There are lots of things that bureaucracies and empire builders and silo protectors don’t want to happen, but don’t want is not the same as can’t. Sheer, unbendable force of will is a genuine superpower.

Usually, BBH would insist on six weeks of creative development time for a new campaign. Usually, a client would take weeks to research and approve it.

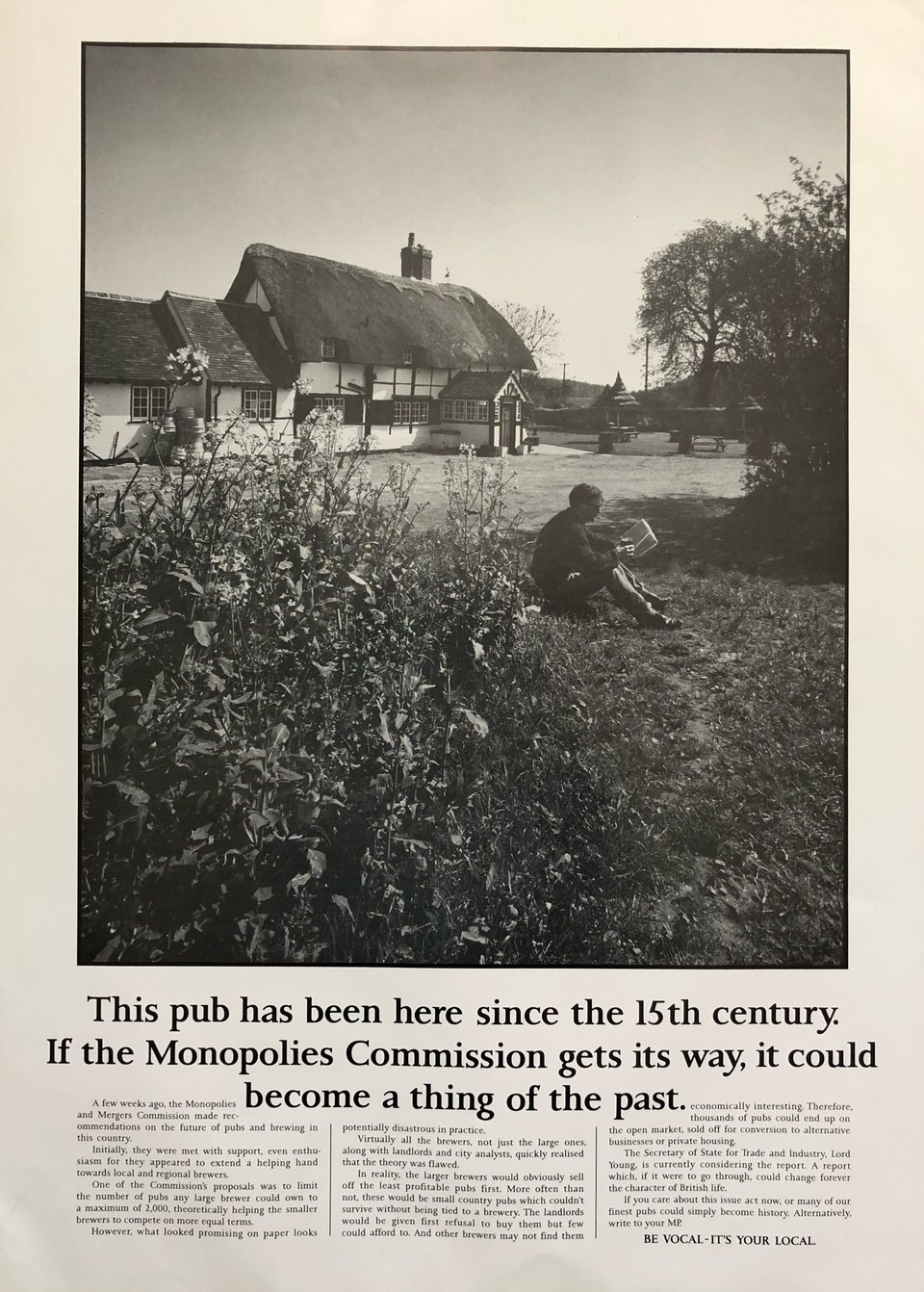

But time was the enemy for The Brewers’ Society, so I watched the rule books go out of the window. Ads were written and approved in one day, shot the next, and then art-worked, produced and printed on the third. This was long before everything went digital, so turning out ads involving photography so quickly was a minor miracle. Necessity is the mother of invention. Desire is the mother of impetus. Desire is the fuel in the bulldozer.

How badly do you want this?

It’s a killer question. An honest answer determines how far you’ll go to make something happen.

The Brewers’ Society wanted to defeat the Monopolies Commission proposal really badly. But it wasn’t enough. The ads were strong executions of a weak argument. The brewer-pub tie was broken.

Agencies can work wonders but advertising has its limitations.

Twenty-three years later I saw corporate desire bulldoze corporate inertia once again.

I worked on Royal Mail’s social media campaign to promote its association with the London 2012 Olympic Games.

Someone at Royal Mail had the idea to issue a commemorative stamp every time Team GB won a gold medal. That in itself was no biggie. They issue commemorative stamps all the time. The kicker that made the idea insane was that each stamp would be designed, printed, distributed and on-sale nationally within twenty-four hours of a medal being won.

This was beyond heresy.

Dozens of people in a dozen departments presented dozens of reasons why this couldn’t be done… until it could and it was.

The top brass at Royal Mail decided to use this idea to prove a point, both to the outside world and (more importantly) to the inside world of their organisation. So they moved mountains.

I sat in meetings in 100 Victoria Embankment and watched desire beget dedication beget deviation beget delight. They wanted it badly enough.

I believe that every organisation - no matter how rigid, siloed, and bureaucratic - is capable of magic. But it needs someone at the top to cast a spell of desire and willpower.

Lesson 2: Connections and consequences

The Brewers’ Society campaign was fast and furious. Graduate training taught me how advertising was made in theory. Now I was seeing how advertising got made in practice - intense practice - by master craftspeople.

The ads were written by Steve Hooper and Dennis Lewis. That’s Dennis pretending to read a book but not pretending to have a pint in the ad below.

It was my first experience of working with Steve and Dennis. In the coming years I worked with them a lot on the Phileas Fogg account. They were the team behind the Made in Medomsley Road, Consett campaign, and they gave me my one and only acting break as an extra in one of their ads. That’s me using a bicycle pump on an aeroplane tyre in the YouTube video.

Steve and Dennis were always patient and generous with their wisdom and advice. And they’d accumulated some wonderful anecdotes.

The Brewers’ Society campaign was produced by the agency’s head of production, Mark Cramphorn. All in all it was a top team to tag along with.

Steve and Dennis did their thing during the day. Mark covered the night shift. I sometimes did both.

Mark took me on a tour of East End production houses, showing me all the things that happened - usually overnight - to turn photography, art direction, and typography into the finished article in newsprint.

In those analogue days, print production involved a tangled web of artisan enterprises. Seeing it happen at close quarters brought home to me the connections behind the advertising process. I could see the dominoes and the order in which they had to fall.

A misguided propaganda campaign was a formative experience for this greenhorn account manager.

I properly understood the people and processes behind every line item on a production estimate.

I properly understood the consequences of not spotting a mistake and having to make a change once the process was underway. I’d met the people who’d have to work extra time overnight to put things right. I could picture the expensive chain of events to reset the dominoes and start them running again.

The importance of quality control was seared into my soul. And it stayed with me long after digitisation made last-minute changes easy, cheap, and therefore a fact of life. There was more attention to detail, less dithering and less last-minute meddling in the analogue era.

I’m glad I learned my trade in an era when an unspotted typo would cost hundreds of pounds at my employer’s expense to put right. It instilled in me the buck-stops-here accountability and the professional paranoia that have served me and saved me for more than three decades.

Two lessons from the Propaganda School of Advertising, and two associated superpowers:

Applied desire is a charismatic superpower that makes apparently impossible things achievable. Force of will gets an idea off the PowerPoint slides and out into the world.

Professional paranoia is a clairvoyant superpower that keeps you one step ahead of problems and their consequences. It smooths the path, keeps you out of trouble, and avoids expensive mistakes.

Maybe try this too: No fat, no flavour, a post about the importance of fun in the advertising process.

And/or try this: Magicians and conspirators, a post about grand designs and ideas to conjure with, and the conspiracy that’s required to make them happen.

Add a comment: