Mixtaping my metaphors

Mixtaping my metaphors

I’ve made you a mixtape.

It’s a mixtape of metaphors and thoughts about metaphors (mine and other people’s).

Of course, calling a newsletter a mixtape is itself a metaphor. Writing about metaphors quickly becomes meta-metaphorical.

Every metaphor (every track) prompted me to think of another one. This started out as a C60 but it’s ended up as a C120. It’s easy to get carried away with metaphors.

As Paul Whitehouse might have said, “Int metaphors brilliant?!”

Each section is self-contained so you don’t have to read it all at once. But the intent is that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Like all mixtapes, it’s a homemade concept album. The concept for this mixtape is Power, precision, and panache.

And here’s the playlist:

Power, precision, and panache

Sheep dipping

Making the abstract concrete

Wild beasts and dystopian orangutans

Nemawashi

The master of metaphor

Marketing metaphors are wishful thinking

The grapevine

Top bombing

Metaphor in strategy

Indigenous metaphor

Elementary particles (coda)

Power, precision, and panache

By my late teens, my dad and I were evenly matched golfers, which introduced some lighthearted needle into our games. Whenever dad hit the perfect tee shot, bisecting the fairway with a bit of right-to-left draw, he’d turn to me with affected smugness and say that his drive had the Three Ps - power, precision, and panache.

It’s a potent combo that defines the superstars in many sports. There are plenty of tournament-winning tennis players whose ground strokes have power and precision, but the ones we love are those who execute with panache. You need all three Ps for star quality. Think McEnroe in tennis. Think Cantona, Bergkamp, or Thierry Henry in football.

We want the technical excellence, but we also want the artistry, the flair, and the entirely justified swagger.

The best ads have the Three Ps. The most effective advertising is based on a precise insight, has a powerful idea, and is executed with panache.

And the same goes for metaphors. The most effective metaphors have the Three Ps too.

If you use metaphor, it has to be good. No, it has to be perfect. Just as there is nothing so awe-inspiring as a metaphor that sparks the imagination, there is nothing so dispiriting as an inept one - or hopeless cliche. Let the metaphor maker beware... Metaphors must be original, invented by the writer for the story at hand. A metaphor has the shelf life of a fresh vegetable.

Constance Hale, Sin and Syntax (How to craft wicked good prose)

Sheep dipping

I sat next to a former HR Director at a dinner. Her world and mine overlapped in the realm of internal comms. We talked about how big companies roll out important initiatives across their organisations.

N.B. The idea of rolling out is itself metaphorical language. A new initiative is rolled out over the organisation like a carpet. The objective inferred from the metaphor is coverage. Moreover, the objective is visible coverage. It’s at least as important to be seen to have rolled out as it is to have rolled out effectively.

My dinner companion coined the phrase ‘sheep dipping’ to describe what happens when this rolling out is done badly.

It’s a devastating metaphor. It has the three Ps. Its power comes from it being a visual idea that uses concrete language. ‘Sheep dipping’ will conjur a similar image in the head of everyone who hears it.

And it precisely and powerfully encapsulates a practice that involves a short, involuntary immersion, after which the subjects shake themselves off and carry on as before; processed but none the wiser.

Therein also lies its panache. Sheep dipping is an imposition. It’s imposed on hapless subjects ‘for their own good’, without prior consultation. The metaphor perfectly captures the counter-productive nature of these tick-box immersion processes. Treating people like sheep, rubbing their noses in their lack of agency, is demoralising and breeds resentment.

Making the abstract concrete

Making abstract concepts concrete is the neat trick that all the best metaphors pull off.

The etymology of metaphor is Greek words that mean to carry across. A metaphor carries meaning across from one domain to another.

In so doing, metaphors satisfy our instinct to make concepts visual or tactile. A metaphor is a strategy for normalising the weird, or as Venkatesh Rao puts it:

A conceptual metaphor is a systematic structuring of meaning in one domain in terms of our understanding of another domain. Here is a simple example: "He gathered his thoughts." Thoughts, literally, are patterns of neural firings. You cannot "gather" them. But the phrase structures our understanding of thought in terms of our understanding of tactile manipulation of a collection of solid objects... Conceptual metaphors lend meaning not just to the things we say with language, but to our perceptions of the world and to the behaviours we enact.

Venkatesh Rao, Tempo (Timing, tactics and strategy in narrative-driven decision making)

Wild beasts and dystopian orangutans

How do you normalise the weird and worrying idea of human relationships with AI? With a metaphor of course. You associate an abstract, unknown concept with a more familiar, concrete set of categories that use visual language. Take it away, James…

This way of seeing the world has produced a three-tiered classification system for the kinds of animals we encounter: pets, livestock and wild beasts, each with their own attributes and attitudes. In transferring this analogy to the world of AI, it seems evident that thus far we have mostly created domesticated machines of the first kind, we have begun to corral a feedlot of the second, and we live in fear of unleashing the third.

James Bridle, Ways Of Being

When we encounter AI technology, are we dealing with a pet, with livestock, or a wild beast?

Talking of unleashing AI in wild beast form, here’s another metaphor.

Edinburgh University PhD student, Elliot Fosong, shared this metaphor as part of a talk on AI Risk, which is the field of his doctorate research project.

If we think of AI as a wild beast, as an existential risk to humanity, we picture it as a malevolent actor. We imagine that the AI will deliberately act to inflict harm or death. Fosong thinks differently. He posited that if we do meet a sticky end at the hands of AI, it’s more likely that we’ll do so as collateral damage than as targeted victims.

And he used a metaphor involving orangutans to make his point.

Orangutans are critically endangered because of human actions. But endangering orangutans is not deliberate, targeted behaviour. The destruction of habitat is commercially motivated rather than sadistic. It’s just that humans are a little more intelligent than orangutans, and we care about other things (capitalism) more than the survival of their species.

What if AI becomes just a little more intelligent than humans and cares more about other goals than it does about looking out for us? There’s no malevolence in this scenario, but these could be the conditions for carnage.

Remember the orangutans the next time you read an overexcited and under-critical eulogy to AI on LinkedIn. (And you will remember orangutans because their relationship with us is a powerful and precise metaphor for a possible version of our relationship with AI.)

Nemawashi

The Japanese have beautiful ideas and they express them beautifully. Somehow Japanese ideas don’t seem to lose a lot in translation (I’m sure they do from a Japanese perspective). Let’s agree that they retain enough of their beauty, their innate poetry, to make them fresh and remarkable in English.

Nemawashi is a beautiful metaphor for seeding an idea; well, less about seeding and more about rooting actually:

Before Japanese company members sign off on a proposal, consensus building starts with informal, face-to-face discussions. This process of informally making a proposal, getting input, and solidifying support is called nemawashi. Literally meaning "root binding," nemawashi is a gardening term that refers to a process of preparing the roots of a plant or tree for transplanting, which protects them from damage. Similarly, nemawashi protects a Japanese organisation from damage caused by disagreement or lack of commitment and follow-through.

Erin Meyer, The Culture Map

The practice of nemawashi flushes out objections and agendas before the stakes for a new idea get too high. And it’s a process that allows an idea to be made stronger by diverse voices.

In other words, nemawashi describes the fine art of building consensus without selling; or the art of not being a hostage to fortune; or the art of not leaving things to chance.

“I’m going to help this idea survive and thrive by attending to its roots before I plant it out in the wild.”

Nemawashi is another Three P metaphor.

The master of metaphor

Nemawashi is a poetic metaphor. In fact, poetry is a candidate for the fourth P of effective metaphors. Or maybe poetry is the product of the Three Ps.

Power x Precision x Panache = Poetry

And that brings us, inevitably, to Shakespeare: the master of the profound and the poignant wrapped in the poetic (More Ps). And when it comes to gorgeous, famous Shakespearian metaphors, how long have you got? Here are just a few:

“The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” Hamlet

“All the world’s a stage” As You Like It

“Love is a smoke made with the fume of sighs” Romeo and Juliet

“Now is the winter of our discontent” Richard III

“the green-eyed monster” Othello

And let’s not forget ideas like the pound of flesh in The Merchant of Venice. It was a literal device in the play, but it’s since been adopted as a metaphor for any unreasonable demand.

Marketing metaphors are wishful thinking

I hate the idea of driving traffic to a website.

It’s a disrespectful idea. It’s as disrespectful as referring to people as consumers. Like sheep dipping, it’s a metaphor that strips agency from its subject. Only in this case it’s whipping cattle into a stampede rather that throwing sheep into a bath of hazchems.

Driving traffic is two metaphors in one, a metaphorical verb and a metaphorical noun. The verb strips agency from its subject, and the noun is impersonal. It’s curious that marketing, a discipline that prides itself on a people-centric ideology, should so readily adopt such a dehumanising metaphor.

Driving traffic is a metaphor that works on the same level as gathering our thoughts. Abstract, invisible processes of the brain or the Internet are rendered concrete and visual by a concept from another domain.

Like many marketing metaphors, driving traffic is a comforting fiction. It’s wishful thinking. Have you ever been “driven” to a website? Nor have I. I’ve been enticed or intrigued to follow a link, but never driven.

Marketing is a sucker for comforting fictions, many of which present as metaphors.

The marketing funnel is a metaphor. It makes the abstract psychology of decision-making processes visual and concrete. Customers being coaxed or sliding inexorably towards a sale. It’s a seductive idea. It’s a comforting fiction.

The customer journey is a metaphor.

Going viral is a metaphor.

A campaign is a metaphor.

Marketing is as prolific with its metaphors as Shakespeare, but much less poetic.

Marketing metaphors have power but they lack precision. They turn abstract, messy processes into concrete but broken models (some of which are more useful than others.)

Because of this, marketing metaphors seduce us into wishful thinking and cage us in cliché.

The grapevine

The grapevine is a metaphor for word of mouth communication. I heard it through the grapevine.

And I can’t think grapevine without thinking Levi’s.

The ad is a metaphor. The idea for the ad is a metaphor.

The Levi’s 501 campaign was about rebellion. Jeans were invented as hard-wearing blue-collar work clothes. They were worn by stevedores and refuse collectors. When James Dean’s generation started to wear jeans casually, their fashion statement was a blatant act of rebellion against the social mores of the time.

Nick Kamen stripping down to his boxer shorts in a public space was a sexy act of rebellion. And it was a metaphor for the spirit of rebellion epitomised by the original jean brand.

A powerful idea, precisely aligned with the heritage and essence of the brand, and executed with consummate BBH panache.

Top bombing

The most effective use of celebrity in advertising is when the celebrity is a powerful and precise metaphor for the USP of the brand. When a brand gets this right it’s like pushing water downhill.

For example, Peter Kay’s stand-up comedian persona was a powerful and precise metaphor for the no-nonsense personality of the John Smith’s brand.

As with Levi’s Laundrette, the idea is executed with seemingly effortless panache.

Metaphor in strategy

Roger Martin advocates that strategy is a creative act. It’s an act of imagination more than it’s an act of analysis. Strategy requires us to imagine possible futures that aren’t contained in backward-looking data.

In this HBR article, he argues for couching the intuitive leaps of strategy in terms of metaphors and analogies. A good strategy tells a compelling story of an alternative future. And a powerful metaphor provides a solid foundation for this kind of strategic narrative.

We all know that good stories are anchored by powerful metaphors. Aristotle himself observed, “Ordinary words convey only what we know already; it is from metaphor that we can best get hold of something fresh.” In fact, he believed that mastery of metaphor was the key to rhetorical success: “To be a master of metaphor is the greatest thing by far. It is…a sign of genius,” he wrote.

Roger L. Martin & Tony Golby-Smith, Management is Much More Than a Science, Harvard Business Review, Sep/Oct 2017

That’s one our most fêted strategy thinkers quoting Aristotle.

The idea of building a moat to protect a strategic position is a metaphor. Blue ocean is a strategy metaphor.

In brand strategy the challenger notion of a “lighthouse identity” is a metaphor.

If you’re a strategist you’re a metaphorist.

Indigenous metaphor

This mixtape of metaphors contains Japanese beauty, Shakespearian poetry, and strategic philosophy. The final track is about indigenous wisdom.

Author and Aboriginal scholar, Tyson Yunakporta, extols the importance of connecting our brains and our guts for a healthy, well-balanced system of knowledge. And he contends that this connection isn’t just biological; it must be achieved through cultural practice, through the continual transfer of meaning between the mental and visceral domains through the use of metaphor.

Like Aristotle, he sees metaphor as a cultural and spiritual craft skill. Mastery of metaphor is elusive. Aboriginal life is a decades-long apprenticeship in applied metaphorical thinking.

Deeply appreciating the kind of wisdom contained in Yunkaporta’s book, Sand Talk, is a privilege westerners like me don’t have. I can only pretend to understand this stuff. But that doesn’t stop me admiring it.

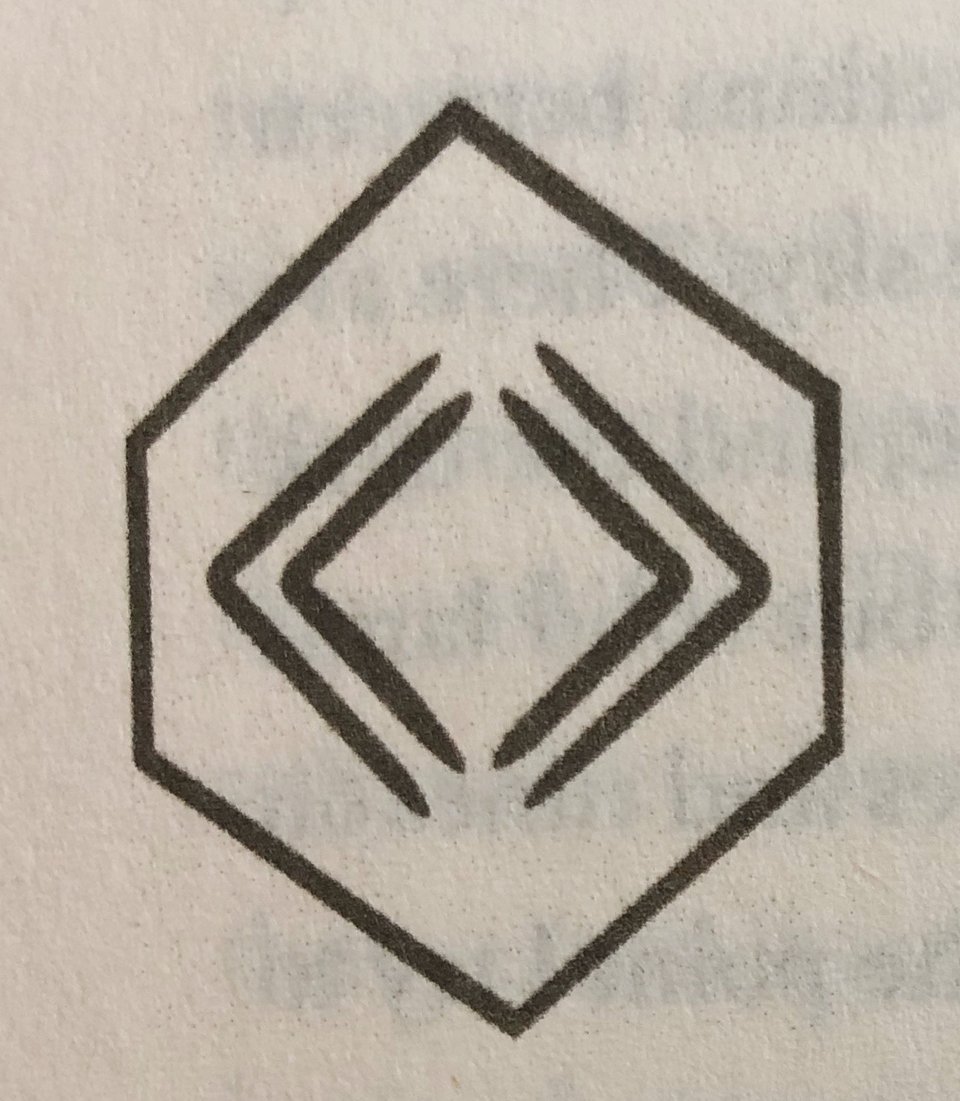

According to Yunkaporta there are layers and layers of metaphorical symbolism within this apparently simple drawing. Separately, the « symbol represents marsupials and the » symbol represents birds (kangaroo and emu), based on the direction that their legs bend at the knee.

And the emu (known to be “malignant narcissist”) is a metaphor for inequality.

Emu’s problem can be seen in the mathematical greater-than/less-than interpretation of the symbol. Emu is a troublemaker who brings into being the most destructive idea in existence: I am greater than you; you are less than me. This is the source of all human misery. Aboriginal society was designed over thousands of years to deal with this problem.

Tyson Yunkaporta, Sand Talk (How indigenous thinking can save the world)

It’s a rich, narrative metaphor. It’s saturated with cultural back stories that give it integrity. In Yunkaporta’s culture, metaphors that lack integrity, that are powerful but imprecise, are seen as a form of curse. He makes his points with panache.

Knowledge transmission must connect both abstract knowledge and concrete application through meaningful metaphors in order to be effective. Without this sacred and joyful act of creation, our systems become unstable and deteriorate. You need cultural metaphors of integrity to do it properly. Working with grounded, complex metaphors that have integrity is the difference between decoration and art, tunes and music, commercialised fetishes and authentic cultural practice. When metaphors have integrity they are multi-layered, with complex levels that may be accessed by people who have prerequisite understandings. Working with metaphors is a point of common ground between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal knowledge systems. We have a long tradition in Aboriginal society of ritual training in the use of metaphor during initiation into higher stages of knowledge... Powerful metaphors create the frameworks for powerful transformation processes, but only if they have that integrity. A metaphor that lacks integrity only damages connectedness - an action that is known as a curse in Aboriginal culture.

Tyson Yunkaporta, Sand Talk (How indigenous thinking can save the world)

We’re at the end of Side B of this mixtape. We started with power, precision, and panache. We finish with the idea that metaphors are sacred.

Elementary particles (coda)

Writing this article brought home how fundamental metaphors are to communication. In the process of editing and rewriting I noticed how many metaphors I’d unintentionally and unconsciously used to illustrate my points. I thought about highlighting all the unintentional metaphors by underlining them or rendering them in coloured text. But I abandoned the idea because there are so many that calling attention to them would have been an unhelpful distraction.

Creativity can be viewed as the act of curating and combining old ideas to create new ones. And a metaphor is a unit of combinatory thinking. It’s a bridge built by the imagination to link two domains. In that sense, given how common they are, given how intuitively and unconsciously we use them, metaphors are the elementary particles, the quarks and bosons, of creative communication. A powerful, precise metaphor is the epitome of creativity.

Add a comment: