Lines in the sand

I make documentaries in my spare time. In a production team meeting last week, Clément said this:

It's the idea of borders, crossings. What fascinates me, always, is to find this language, creative language, to connect the dots between the very intimate, the very personal, and the very macro level, and geopolitics. The dynamics of power.

Clément Guerra, Activist & Documentary filmmaker.

I was sensitised to this idea by a recent trip to Berlin. As you do, we immersed ourselves in the history of the Wall before and during our visit. I was reading a wee treasure of a novel called The Short End of the Sonnenallee by Thomas Brussig (translated by Jonathan Franzen and Jenny Watson.)

The Sonnenallee is in the south east of the city. It's 5km long. There was a Berlin Wall checkpoint at its eastern end. The placement of the Wall meant that roughly 4.9km of the boulevard was on the western side, leaving the "short end" in the east, in the former GDR. The novel describes the impact of separation on the residents of the short end; cut off from family and former neighbours on the western side, and taunted by tourists looking over the Wall from an observation platform. The book is both sweet and satirical. People find the cracks in any system. People create hacks for any system. And people abuse any system if you give them power; especially if you also give them a uniform. For an author, these dynamics are a rich source of humour and pathos.

It seems that this kind of humour comes naturally to eastern Europeans. Asked by Tyler Cowan about the different senses of humour in western and eastern Europe, Jacob Mikanowski, author and historian, had this to say:

The Eastern Europeans have a real sense of humour... a sense of the tragic, a sense of the absurd, a sense of how those two go together.

Jacob Mikanowski

In The Short End of The Sonnenallee, the tragic and absurd episodes all revolve around the personal and intimate consequences of Cold War geopolitics.

Clément's comment also brought back memories of crossing former Soviet borders in an ambulance.

Some friends and I bought the ambulance for £3,500 on ebay and drove it across Central Asia to Ulaanbaatar in Mongolia. You should do The Mongol Rally one day. It will change your life.

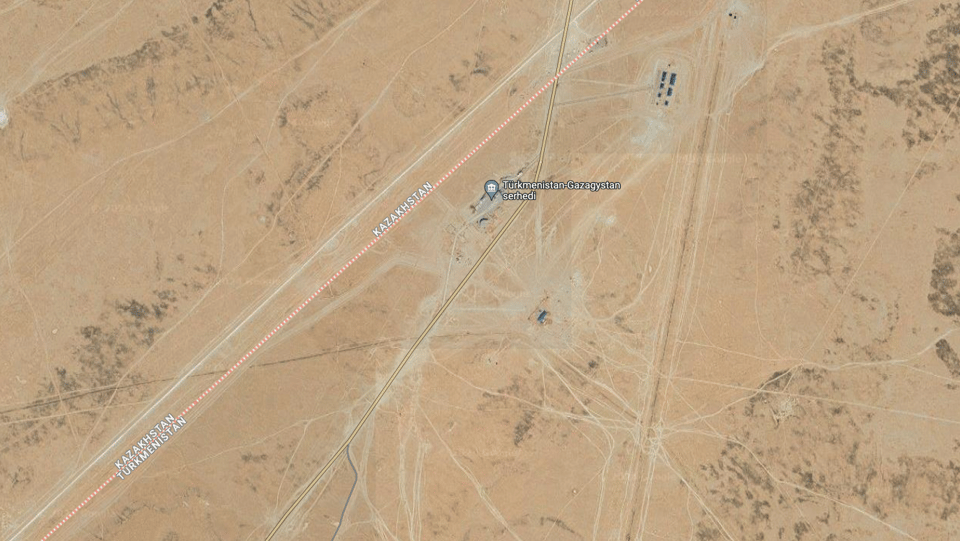

By the time we limped across the finish line we'd driven more than a third of the circumference of the earth in an entirely unsuitable vehicle, across baking deserts and along the second highest mountain highway in the world. And yet a disproportionate amount of the stories we brought back took place at the border crossings. A disproportionate amount of absurd things happened as we went from one side of an arbitrary line in the sand to the other.

Crossing a desert or high mountain border on foot or in a vehicle is nothing like passport control at an airport. Flying into a foreign country is a sanitised experience; homogenous, sterile, mildly bureaucratic, mildly irritating. Unless you're on some Interpol wanted list, or you're smuggling contraband, there's no jeopardy in an airport.

In the desert you are acutely aware of how geopolitics become intimate and personal. These crossings are less iconic than the Berlin Wall but they have similar effects. They disrupt families, tribes, communities, and they interrupt supply chains. They create an ideal habitat for kleptocrats. They are crucibles of the absurd.

The worst thing that happened at one of these borders was when one of our team tried to cross from north eastern Kazakhstan into Russia with the wrong dates on his visa. He'd had similar problems earlier in the trip and we'd had to leave him in Turkmenistan because he didn't have the right visa to get into Uzbekistan. If we'd waited, our visas would have become invalid too. In any case, his brusque, cavalier, entitled manner was wearing thin. He'd almost talked us into trouble rather than out of it on a couple of previous occasions, so it wasn't the most difficult decision to press on without him. He was supposed to have resolved all of his visa issues by the time he rejoined us, but clearly hadn't. So he proposed to bluff and blag his way into Russia if someone spotted his dodgy visa, which of course they did. We told him that we'd disown him if he tried this, which of course he did. He was dragged into an interrogation room (on the Kazakh side fortunately for him) and we didn't see him again for the rest of the rally. He eventually sorted his visa and hitched a ride with another team.

The funniest thing that happened was only amusing in hindsight. My friend's dad, Callum (aged 70), set off an alarm as we crossed from Turkmenistan into Uzbekistan. My friend had already passed through in the ambulance and it was my turn to be the first of the other two to go through on foot. So we had no idea why he hadn't appeared some 60 minutes later, and no way to do anything about it. Meanwhile, surrounded by soldiers pointing AK47s, it slowly dawned on Callum that the radioactive implants treating his prostate cancer had triggered the alarm. He overcame this non-trivial communication challenge by pointing at the yellow and black radiation hazard symbol on the scanner and then pointing at his crotch. Even more slowly it dawned on the soldiers what this strange mime act meant. There was much mirth when the penny finally dropped. The fact that Callum's pure white beard made him look like Santa Claus probably helped.

In the queues to cross these borders you mix with long-distance lorry drivers, short-distance entrepreneurs, and the continuous ebb and flow of local people going about their daily business; visiting family or gathering resources on the other side. It's mundane and menacing at the same time. Your only defences against attempted shakedowns are patience, feigned stupidity, and a well-rehearsed impassive face that doesn't betray your adrenaline levels. These tricks usually work once the man (it's always a man) in the uniform decides that he's wasting time on you that could be devoted to an easier mark.

The conversation with Clément moved from borders between countries to the ideological barriers between people. And, from there, to the self-righteous walls that each individual erects between themself and "the other". This is the crux of the film project we're working on. We are all human Berlins, and our walls need to come down to create safe crossings for alien ideas and alternative perspectives. Only then can we hope to address the binary thinking and tribal hostility that defines our politics, our conflicts, and our culture wars. Alastair Bonnett writes about the geopolitics of borders in Off The Map, but when he talks about arrogance and modesty, demand and denial, he could equally well be describing the psychology of our inner barriers.

Borders are about claims to land, but as soon as you draw one you limit yourself. Every border is also an act of denial, an acknowledgement of another's rights. By contrast, the claim to want no borders, much prized by Business Class executives and anti-capitalist activists alike, is a claim to the whole world. Borders have a far more ambivalent and complex relationship to territory; they combine both arrogance and modesty, both demand and denial.

From Off The Map by Alastair Bonnett

Back to Berlin. Back to The Short End of the Sonnenallee. This is the last paragraph of the book. And it's the end of this post. It's a lovely and fitting contemplation on nostalgia, peace making, and a life devoted to accumulating stories

If you truly want to preserve what's happened, you can't indulge in memories. Human memory is far too comforting a process to simply capture the past; it's the opposite of what it pretends to be. For memory is capable of more, much more: it stubbornly performs the miracle of making peace with the past, wherein every old grudge evaporates and the soft veil of nostalgia settles over all the things that once felt sharp and lacerating. Happy people have bad memory but rich memories.

From The Short End of The Sonnenallee by Thomas Brussig.

Add a comment: