Boffins and battle scars

Archetypes are the ogre of brand strategy.

Archetype is a trigger word. Be ready for the mob and the pitchforks if you mention archetypes on a professional platform. Be ready for scorn, affected vehemence, and an intellectual ticking off. Be ready to be patronised. People like to rag on archetypes.

Ironically this kind of ragging has become a stereotype. Anti-archetype ragging is itself typical behaviour.

The raggers are mostly intellectual planner types deriding the psychological theory behind archetypes; deriding the naivety of anyone who uses archetypes as a basis for brand strategy. The details of this derision aren’t relevant to this article so I’ll spare you. Suffice to say that these people have come to a common conclusion: archetypes are for pseuds (apparently).

I get that. They have a point. They have several valid points actually. But this kind of rigid insistence on theoretical purity can blind people to the context-specific utility of an idea.

Wizards and Jedis.

I’ve never used archetypes to inform strategy. But I have used them to help clients with execution. In the right circumstances, archetypes are a user-friendly aid to storytelling. Forget all the hifalutin upstream arguments about archetypes. They’re darn useful if you don’t consider yourself a natural storyteller, and you find yourself downstream in the weeds of creation needing to publish something.

Clients have a love/hate relationship with storytelling. They want a piece of it but they don’t feel confident doing it. It’s a dark art. It’s a marketing lightsaber. You have to be a wizard or a Jedi to use it.

So any construct that makes storytelling easier should be welcomed. Who cares if it’s not entirely scientific?

Not a dictionary.

I just finished a book called Tempo by Venkatesh Rao. The subtitle - Timing, Tactics and Strategy in Narrative-Driven Decision-Making - makes it sound like one of “those” business books. It’s anything but. It’s imaginative and philosophical. It’s quirky. It’s like a theory of relativity for how to be and what to do at work, but also in life. Lots to think about. Lots of dog-eared pages. I’ll be going back to it.

For our purposes here and now, the keyword in the subtitle is “narrative”, and the author has quite a lot to say about archetypes, including the following statements:

Archetypes are your mental models of people.

Archetypes can be deeply thought-provoking constructs.

Archetypes are critical. We couldn’t function without them.

Whatever your self-archetype,it is the construct through which your sense of self inexorably gathers momentum through life.

Archetypes are an artistic thinking tool, not a dictionary.

Venkatesh Rao, Tempo

Venkatesh and I see eye to eye on that last one. There’s nothing definitive about archetypes, but they are stimulating conceits.

I occasionally use archetypes to help get my clients in character for storytelling. I use archetypes to give them a mental model of the role they’re playing when they write or talk on behalf of their brand.

For example:

Archetypal sagacity.

A lot of my work is advising advisers. I’ve consulted to consultants. And I’ve charged by the hour to a law firm. In each case, the upstream brand work has led to downstream storytelling of some description. Enter archetypes. Enter one archetype in particular.

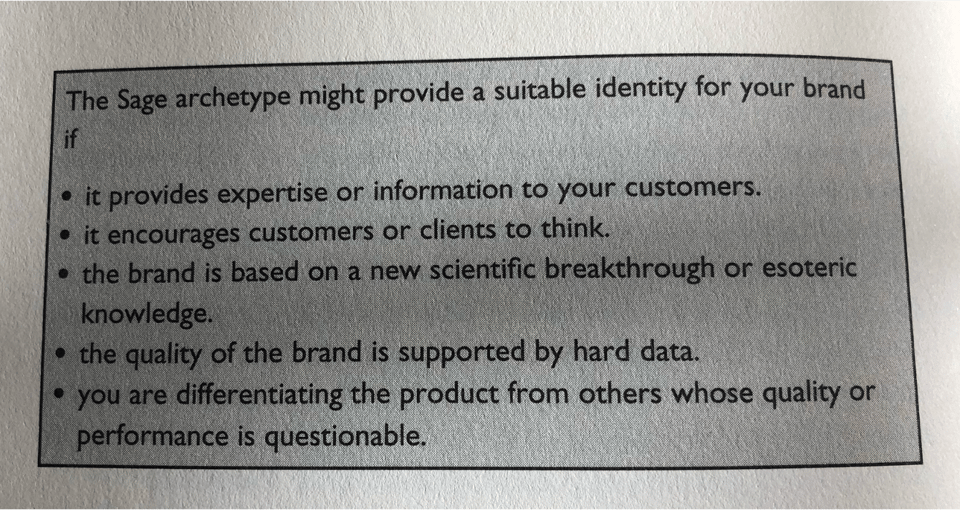

It doesn’t take superhuman sagacity to work out that the dominant archetype for an advisory business is The Sage.

The Sage provides wisdom, counsel, coaching, or mentoring to help the hero of the story on their journey. By definition, therefore, the Sage is never the hero. The Sage is a service provider. The Sage is an adviser. So of course the Sage is the patron archetype of consultants, for whom the client is always the hero.

Sage role models come in all shapes, sizes, genders, ages, and ethnicities. Mary Poppins. Brains from Thunderbirds. The Oracle from The Matrix. Professor Dumbledore. Star Wars has two famous sages in Yoda and Obi Wan. The Lord of The Rings has two sages in Gandalf and Galadriel.

I like it when sages come in pairs, in the movies that is. It doesn’t work so well when a client brings in two consultants at once; spoiled broth and all that.

Boffins and battle scars.

My favourite Sage duo is Hooper and Quint from Jaws. They’re a case study in how not to hire advisers. Their apparently complementary methods only create conflict, leading to conflicting advice.

Quint and Hooper are hired to help Chief of Police Brody catch the man-eating shark that is terrorising Amity Island. This is the only thing they have in common.

Hooper is a marine biologist. His knowledge of sharks is scientific and his interest comes from a place of love and admiration.

This is what happens. It indicates the non-frenzied feeding of a large squalus - possibly Longimanus or Isurus Glaucus. Now the enormous amount of tissue loss prevents any detailed analysis; however the attacking squalus must be considerably larger than any normal squalus found in these waters.

Hooper

Quint is a fisherman and ex-navy seaman. In the war his ship was sunk by a Japanese torpedo and he watched, helpless, as many of his friends were killed by sharks while waiting to be rescued. His knowledge of sharks is empirical and his interest comes from a place of hatred.

Quint and Hooper have little time for each other and don’t bother to hide it, except when they’re drunk. Quint never misses an opportunity to be dismissive of Hooper.

You have city hands, Mr. Hooper. You been countin' money all your life.

Quint

What we have here are two sub-archetypes in the Sage family: the boffin and the battle-scarred veteran.

And both of these sub-archetypes exist in every advisory firm that I’ve advised, although I haven’t met any larger-than-life caricatures like Quint and Hooper yet. More’s the pity.

Boffins tend to be the younger advisers. Their academic credentials are impeccable. Their vocational qualifications are fresh and relevant. They’re at the cutting edge of theory in their field of expertise. They make sure that their clients can see what’s coming and don’t miss any tricks.

The veterans are pragmatism personified. They’re alumni of the university of life and the school of hard knocks. They’ve had the t-shirt for years (it’s faded and a little yellow under the arms these days). They’ve got every knack and they’ve used every hack. They’re sceptical of cutting edge theory unless it has been shown to survive contact with the real world. They fix things. They unblock things. They head problems off at the pass. They keep their clients out of trouble.

Inhabiting is uninhibiting.

We’ve all met boffins and (figuratively) battle-scarred veterans. They’re easy characters to imagine, which makes them easy characters to inhabit, especially if you are a boffin or a veteran in real life.

When you’re staring down the barrel of a blank sheet of paper, anything that gets some words onto the page is a good idea. People who advise for a living might not see themselves as natural storytellers, even if most of them actually are. Channeling their inner Quint or Hooper can provide just the jump start they need. I’ve seen it work.

If writing in character, according to an archetype, gets the story ball rolling, who cares whether the underlying psychology is watertight? It might not turn you into Orwell. But nor will it turn you into an ogre.

Add a comment: