SWORDS AND SOBRIETY ⚔️

THE HARDEST THING IS GETTING BETTER

To paraphrase Jacob Gellar—who is better at this than me and who you should all follow—”Sekiro is the hardest of FromSoftware’s notoriously hard sword games.”

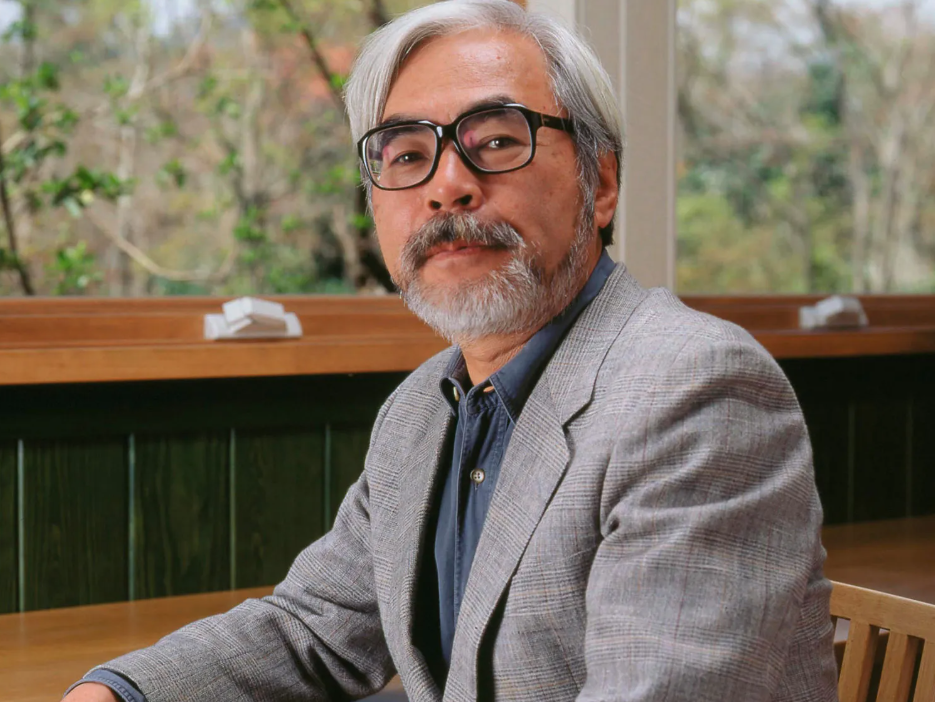

If you’re not familiar with FromSoftware, they’re the Japanese game developer lead by visionary creative, Hidetaka Miyazaki. For those of you thinking, “The Ghibli guy?” Nope, that’s the OTHER Miyazaki. Though the two are contemporaries and one’s work (Hayao) definitely influences the other’s (Hidetaka). For the visual learners, this handsome old curmudgeon is the Miyazaki who makes the groundbreaking anime:

And this impish little critter is the Miyazaki we’ll be discussing, the one behind the groundbreaking video games that have utterly consumed my life:

Hidetaka Miyazaki is the creative force behind the games known colloquially as “The Soulsborne Series”—Soulsborne being a portmanteau of the studio’s Dark Souls series and the standalone title Bloodborne. To put it as simply as possible (which is ironic if you’ve ever played a Soulsborne game because they’re anything but simple), the Soulsborne games are a series of Action RPGs without a named protagonist with an emphasis on exploration, vague narrative cohesion, and grueling boss battles.

To put it in even more basic terms: THEY’RE FUCKING HARD.

In the last six years, the studio has had unprecedented success with two games, one you’ve likely heard of—Elden Ring (2022)—and one you maybe haven’t—Sekiro (2019). While Elden Ring primarily adapted the familiar mechanical and narrative formulas of previous Dark Souls titles to an Open World game format, Sekiro experimented with the formula in drastic ways that made it more focused and, in my opinion, far more difficult than any of the games before it.

Paramount to that focus is the fact that Sekiro, unlike any other Soulsborne game, follows a named protagonist. You don’t play as RANDOM SAD SWORD GUY with a set of familiar RPG statistics, weapons, and spells to level up in your pursuit of power; you play as Wolf, the shinobi, who, to be fair, is also a profoundly sad sword guy. But importantly, he’s just Wolf. And you are just you. So for Wolf to be Wolf, you have to be the best Wolf you can be. The fate of the world and no less than two adorable children rests on it. To put it mildly, the stakes are high. And there are very few ways to swing them in your favor.

Sure you can augment Wolf’s damage in some ways, and yes you can add combos and counters to his repertoire that make him more efficient in combat, but at the end of the day—and the end of the game—there’s just Wolf and his sword. And Wolf is only as good with his sword as you, the player, can make him.

This choice on FromSoft’s part creates what, to this gamer, is the most brilliant example of ludonarrative harmony ever designed. You’re welcome if you learned a new term today. If you’re interested in learning more about how Sekiro achieves this and how it fits into The larger tapestry of FromSoft’s work, I highly suggest you check out this video from Noah Caldwell-Gervais. But for our purposes, I just need you to know that Sekiro is the most difficult, most frustrating, and ultimately most rewarding video game I’ve ever played. And once I finally completed it, I realized that experience mapped perfectly onto my journey into sobriety.

OF ROT AND DEMONS

In Sekiro, Wolf is immortal. But that immortality comes at a cost: every time he dies (read: every time the player fails), the people around him grow sick with something called “Dragon Rot”. The more bad choices you make as a player, the more times you mistime a parry or botch a dodge or lose to a difficult boss, the more the most important people in Wolf’s life get hurt. And if that’s not a great allegory for being an addict I don’t know what is. Because addiction is a social sickness. It doesn’t just affect you, it snakes its tendrils into the lives of everyone who cares about and relies upon you. And when you’re in it, you can see that happening even when you feel powerless to stop it. Much like with Sekiro, you can’t get better till you learn how to make yourself better. And that’s an extremely difficult thing to do.

The parallels continue. Wolf also has a friend, The Sculptor, who helps him along his journey. The Sculptor was once a warrior much like Wolf, but his desire for violence and pain eventually overcame him. In one of the game’s most difficult and hidden boss encounters, you fight THE DEMON OF HATRED, a monstrous, fire slinging maelstrom of anger that was once the Sculptor. In this fight, Wolf gets a glimpse of what will eventually become of him if he succumbs to his own desire for violence and retribution. If he never grows, if he stays locked in this destructive cycle, he will eventually become a demon.

I’ve been in recovery for alcoholism for over seven years now, and despite never having a relapse, I still think of myself as an addict. Any amount of sobriety, be it seven years, seven days, or even seven minutes, is of course something to be celebrated, especially in a society so organized around cruelty and shame, but no level of success, no lack of recidivism, can ever fully take away the feeling that something is lurking inside of you. Something that can emerge at any time to ruin your life and the lives of those around you.

Wolf’s confrontation with the Demon of Hatred (essential to completing the game’s full, canonical narrative) shows him what he will become if he slips back into the darkness, yes, but it also serves a more profound purpose: it shows him that all the difficulty, hardship, and loss he’s endured (and you the gamer have endured with him) was worth it. It holds a mirror up to the thing he fears most, then reminds him that he has everything he needs to defeat that fear. Few things in my life felt as satisfying, cathartic, or personally resonant as finally overcoming the Demon of Hatred. I made Wolf better and in turn, he made me better too.

HARDER BUT BETTER

When I decided to pick Sekiro back up and dedicate myself to fully completing it, Donald Trump had just taken office for a second time, my trans loved ones were rapidly losing their rights, and the crisis in Gaza had been going on for well over a year. It felt like everywhere I looked, the spectral hand of fascism was closing in more and more around myself, my values, and my people. I found myself suddenly compelled to overcome something I once thought was impossible. So I booted up Sekiro for the first time in years.

The rhythms came back to me quickly and I spent two days (yes, two entire working days) finally figuring out how to overcome the difficult boss battle against Wolf’s surrogate father, Owl. This was the fight that had ultimately made me put Sekiro down in the first place and once I managed to beat it, I knew there was no challenge the game could present that I wouldn’t overcome.

Because when you stop drinking, that first day feels impossible. But then you go to bed sober and wake up the same way the next day and you know then that you can at least make it one day. Then you do that for the next 30 days and your body starts to reset, starts to learn who it is without alcohol. And you think, if I can do 30, I can do 90. So you do 90 and then your face starts to change, the bloating goes away, the redness in your eyes and your cheeks recedes. Then you do six months, then a year, then three years, then seven…then Owl Father, Demon of Hatred, Genichiro, Sword Saint Ishiin.

And one day you’re over seven years sober, Playstation controller in your hand like a thunderbolt, Sekiro’s final cutscene playing out in front of you while you sob and remember what it feels like to truly defeat the impossible. And then you remember that you’ve done it before and will do it again.

For years, I’ve had this saying about my sobriety, a bit of shorthand if you will that I can use when the inevitable, “What’s it like being sober,” question comes up. I say, “It’s harder, but better.” I even have it tattooed on my skin. I think maybe I’ll add Wolf’s swords to the tattoo now, too.