You're all on the shortlist!

Welcome to another edition of this Mailing List!

With each email I'm sharing material that has inspired me recently. I'm hoping it will inspire you, too. If you want to support my work, you can sign up for my Patreon. This will get you access to exclusive material every week.

If Patreon is not your thing but you enjoy what I'm doing, feel free to send me a little something via Paypal. I'll use the funds to pay for the fee the service provider of this Mailing List charges me every month. If there's money left, I'll invest it into the Japanese green tea that fuels much of my creative work.

The “shortlist” of the Arles book awards has been published: “122 books have been shortlisted in all categories”. Yes, you read that right. One hundred twenty two books. On the “shortlist”. Words have no meaning any longer. Short now means long, and long means who knows what.

So I made a meme and shared it on Instagram, hoping that even the non-Americans will have some knowledge of the Oprah Winfrey show. If you have never seen this, watch the video clip. It’s half a minute long, and it’s insane in all kinds of ways.

I have some thoughts on all those book awards with their typically enormous “shortlists” (I shared something brief on IG). I also have some thoughts on those many “Talent” issues now regularly churned out by photography magazines.

At some stage, everybody will be a shortlisted talent.

But honestly, I don’t think it will make any difference if this writer suggests that none of those awards and talent lists do anyone a real favour.

Casino capitalism has taken over the world of photography. Unless enough people get together to create something better, some guy writing stuff in the New England countryside isn’t going to make any difference.

Onto the material I have collected for you then.

After all, New Yorker staff writer Kyle Chayka wrote that “perfect link blogging is backkkk [sic!] and it's in newsletters”.

Speaking of Chayka, his article about "Voice, taste, trust, scarcity” is interesting. On the one hand, it’s filled with all kind of corporate thinking that no artist should even have to deal with.

On the other hand, if you ignore the media context, most of the lessons do apply for artists as well. For example:

You need reliability. Whether you have a YouTube channel or a link-dump newsletter, you need to keep delivering what you promise to deliver.

Or:

You need to provide things that other publications or creators aren’t providing.

Switch out the words that don’t apply in an art context for ones that do.

I’m not suggesting that you go about this as if you had a management consultant breathe down your neck. However, for an artist it never hurts to step back and think about these aspects: what is my own, personal voice? How am I communicating what I want to communicate? How can I use what I’m good at to establish my voice?

“It has been almost 16 years since I started writing stories,” Yukiko Tominaga writes, “alternating between Japanese and English. English still scares me, but the language brought me the courage to raise my child in this country, connected me to wonderful people, and gave me the confidence that, with my imagination accompanying me, I could survive not just in the U.S but under any circumstances.”

The following is really quite beautiful, and it changed my mind a little bit about my own place in this world:

When I write in Japanese, I see America more objectively. I am not swayed by opinions around me and often I rediscover why I love this country even though life in the US feels like it’s all about survival. When I write in English, I find Japan and Japanese people to be fascinating. I stop trying to make sense of them and rather let them be and appreciate their complexity as they are. Switching around the two languages frees me from my own stigma. As much as I desire to belong one place, it is a privilege to be a stranger in both my countries.

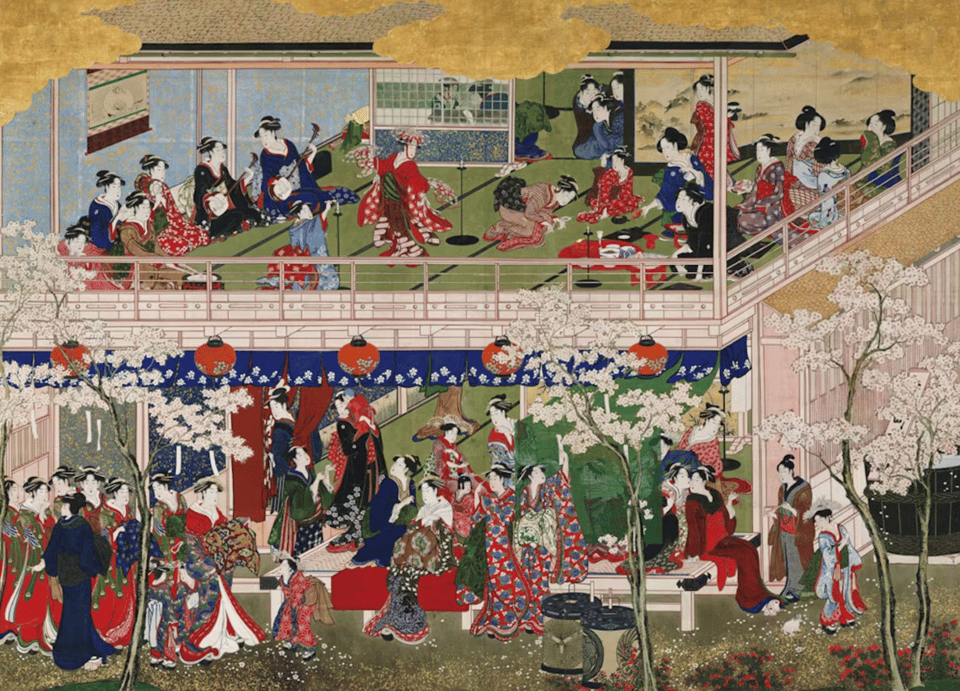

A little while ago, I came across one of the most fascinating and insightful articles I have read in a long time, written by Hiroko Yoda. It talks about our ideas of what’s typically called “the floating world” — the red-light districts in pre-modern Japan — and its actual, absolutely gruesome reality.

The average lifespan of a courtesan was just twenty-two. The vast majority were not considered worthy of proper funerals. Their kimono were stripped for use by other courtesans, and their naked bodies wrapped in straw mats and left at the entrance of a nearby Buddhist temple, for the monks to provide last rites. It was popularly known as Nagekomi-dera, “the throw-away temple,” and contains the remains of some 25,000 former quarter residents. It still stands today.

And that’s not even the worst part. You still want to read the article, because I do think that it’s interesting to know to what extent those lofty art ideas usually associated with prints made around “the floating world” are rooted in an absolutely brutal reality.

If you are active on Instagram, you probably encountered the AI image that spelled out “All eyes on Rafah” a little while ago. The image spawned a bunch of discussions, the German ones of which were easily the most inane ones.

Adrian Daub wrote a lengthy and very intelligent article about the image and reactions: all you need to know.

Meanwhile, the New York Times T Magazine decided to produce the most photolandian navel gazing in a long time, gathering a few photo people to discuss (if that’s the word) The 25 Photos That Defined the Modern Age. To be honest, the one person I was impressed by was Stan Douglas. The rest… Not so much.

I mean a statement such as “Without this documentation by Eugene Smith, I don’t think Minamata and the mercury poisoning would ever have been confronted.” is just absurd. Japanese photographers made work around it, and there was a huge social movement in Japan itself (read up on it here if you’re curious). I’ve always known how limited knowledge in the West is about the rest of the world. But I was still shocked to read this.

The pictures come with separate short essays. I only read one, because I knew all the photographs. If you’re teaching, you might find that collection (the pictures plus the short essays) useful.

I’ve always been puzzled by the statue in front of Boston’s Museum of Fine Art. Maybe it’s because I’m German, and I didn’t grew up in this country. But the statue is profoundly weird (not in a good way). It would seem that this particular issue is now being addressed by the museum.

The article describes the statue as follows: “The figure is a litany of no-fixed-address Native American cliches, a vague mash-up of Navajo (Southwest) and Dakota (Midwest) aesthetics”. From this, a few things immediately follow. Make sure to read the article!

The collection is truly incredible. If you want to see it yourself, this is the link to the Google Drive.

I don’t know whether I would call the imagery in this article describes as collages. However, should we have a debate over collage versus montage, when we could instead be looking at Bertolt Brecht’s work with photographs?

brecht: fragments is the most extensive display to date of the visual material the playwright collected over the course of his career, from newspaper and magazine pictures to photocopies of medieval paintings and images from Chinese theatre.

“There is something hopeful about writing a review,” writes Christine Smallwood, “it’s like putting a message in a bottle or sending up a flare.”

“The four years I worked as a sex worker in San Francisco were a very practical lesson in the mechanics of modern techno-capitalism,” writes Liara Roux, “or whatever this is.”

Even if you’re not interested in learning about sex work (and its rapid online evolution), it’s a most fascinating article, because at least parts of the lessons apply to us all. So much of what I’ve shared over the past few years — Instagram, AI, whatever else — pops up in some form.

And that’s it for today. Here in Western Massachusetts it’s the most perfect late Spring day. The sun is out, and there is a breeze, which is keeping temperatures at bay.

I hope that wherever you are there is an equally beautiful day.

As always thank you for reading!

— Jörg