we are destroying history and culture to fuel the empire

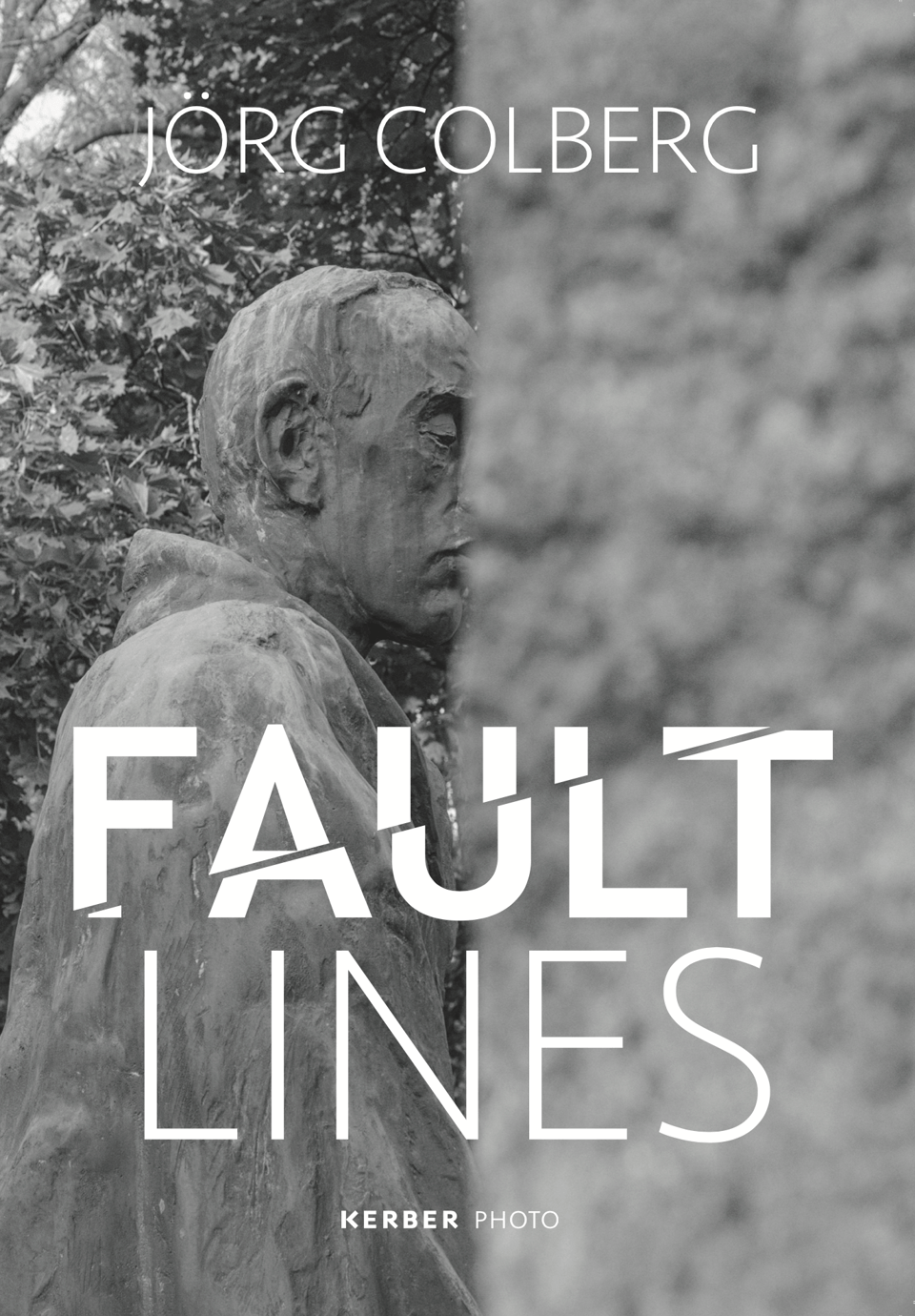

For the larger part of this year, I was working on what has now been released, my second photobook (or rather photo-text book). It’s entitled Fault Lines, and it continues some of the work I did with Vaterland in 2020. The new book was photographed in Hungary, and it includes thoughts by a number of Hungarians I spoke with.

In the broadest sense, Fault Lines is about life under autocracy and how autocrats maintain power by tweaking how the history of their country is told. It’s a book about Hungary in the most obvious sense. But you could swap out a few details, and you’d have a book about any of the other countries where neofascists have gained power (the US joining their ranks in a few weeks).

I don’t know what it was, but this time, thinking about selling the book (I have 300 copies) became a lot more difficult. Maybe it’s because I have become a lot more aware of how difficult this actually is for me (see the email I sent out a few weeks ago).

Regardless, if you want to get a copy of the book, please be in touch, and I can set you up. If you’re interested in a combo pack (the book plus some very nice prints), I got you covered as well.

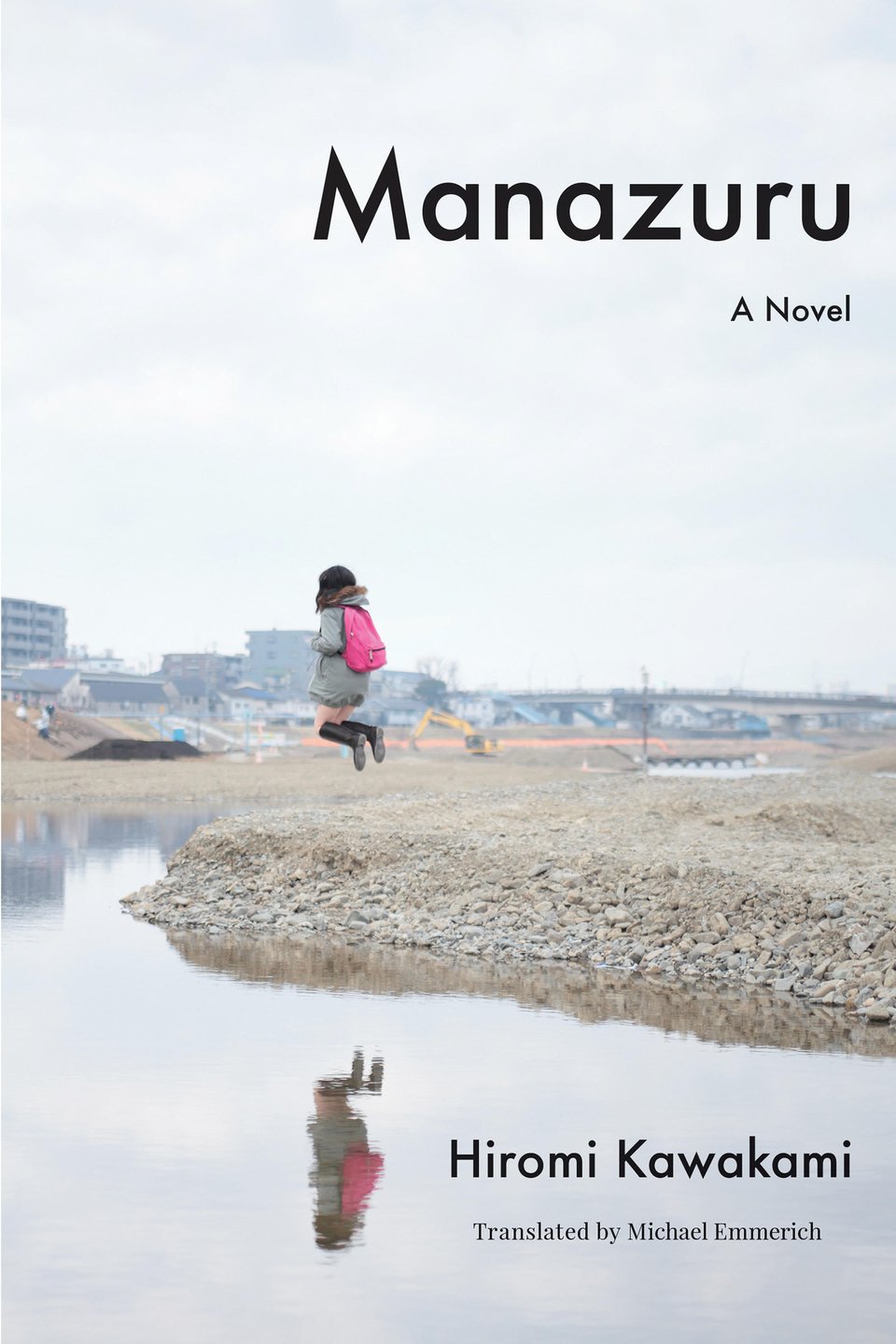

The thing with literature is that you never know when you’ll read the next book that will blow you away. I had read two books by Hiromi Kawakami before, which is why I waited a while before I started Manazuru. I absolutely adored the two earlier books. They were, to use a British term, maybe a little bit twee, but just the right amount of twee.

However, Manazuru was a completely different beast. What a beast it was! Incredible! Quite unlike Strange Weather in Tokyo and The Nakano Thrift Shop.

As much as I love that cover, it has nothing at all to do with the book. Without giving away too much information, the book centers on a middle-aged woman whose husband mysteriously disappeared a decade earlier, leaving her to move back in with her mother to take care of her daughter. In the 10+ years since, she has taken on a lover, a married man she sees regularly. But her thoughts go back to the man who left without leaving a trace.

It’s the kind of book that I’d hate having to write a book blurb for. I don’t think you can outline it easily. In some sense, very little happens; and in other ways, there’s just so much going on, with the protagonist’s inner world merging with what might or might not be magical-realist moments. It’s a deeply affecting book, and I couldn’t recommend it more.

Honestly, if all you know is the material Haruki Murakami produces — oddly stylized stories around male characters who basically have no inner life and female characters that are merely ornaments for the “heroes” — you’ll be blown away by the richness of the writing here.

The other day, I found an article about Elsa’s Housebook: A Woman’s Photojournal, a 1975 photobook by Elsa Dorfman who was close with a lot of poets. They would visit, and she would photograph them. Unfortunately, I have as much connection to poetry as I have to ballet or opera, namely absolutely zero. But it was really interesting to read about the book and its background. And you might enjoy poetry, so you possibly get more out of it than I was.

“For me,” Brian Eno writes, “using AI all too often feels like I’m engaging in a socially useless process, in which I learn almost nothing and then pass on my non-learning to others.”

Nan Goldin is having a major show in Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie. Given how outspoken she has been about Gaza and given that Germany has resorted to suppressing expressions of support for Palestinians in ways that are shameful for a mature democracy, you can probably imagine how well this went: not very. You will want to read this interview with Nan Goldin about her experience.

Karla Kelsey wrote an article about Sophie Calle’s The Sleepers, which is well worth your time. The Sleepers has just been reissued as a book. I’m not 100% convinced that I need it; tomorrow, I’m going to be publishing an article about another new book, the catalogue of a recent US retrospective of the French artist’s work.

I’ve been finding quite a few really searing pieces of writing lately. Here’s another one, a piece on assisted dying — and on changing one’s mind. I started reading it without realizing that I wasn’t quite prepared for what I was getting into. It’s really good writing, but the topic is extremely rough. Reading it felt like sitting on a plane that had just been hit by really bad turbulence. So if you’re feeling vulnerable or if — like many people right now — you’re on edge, maybe save reading it for later.

“When you describe yourself as a “writer” but your writing has become hard to find, it creates a crisis not just of profession, but identity.” This is s.e. smith writing about the internet, in particular what happens when sites you wrote for disappear (as sometimes they do):

Much like the British tossing papyrus and mummies into the hungry maws of steam engines, we are destroying history and culture to fuel the empire, and the empire is profit. The result is internet poisoning, a landscape saturated in misinformation and AI garbage — at best comical, at worst, lethal. For future generations interested in knowing more about the world we live in, it has the potential to make it nearly impossible to untangle fact from fiction, art from fakery. There is something deeply offensive in knowing not only that hundreds of thousands of my words have vanished, but that some LLM is probably crawling through the tattered fragments to churn out mockeries of the very real sources, research, and energy that once backed those words.

I was going to end on a high note or rather on maybe not the most somber of notes. So here’s a recent cat photograph of mine.

With all that said, just a few more words: the year is ending, and I hope that you’re able to enjoy the holidays, whatever those might be for you. And I hope that you’re going to have a Happy New Year!

Thank you for reading along this year! I know it’s difficult these days to get anyone’s attention. So I’m intensely grateful that I have yours in those moments when you read these missives written in a small house at the foot of Mount Sugarloaf.

Be well! Until next year!

— Jörg