To Write Is To Be Sisyphus

It's hardly an original observation to compare the task of writing with Sisyphus'. Any writer will know to what extent they are Sisyphus, performing a tedious task that more often than not ends up being in vain. But there is even more to it than that. In the beginning, you don't even know where the hill is: you often end up pushing that boulder around on what feels like an endless plain, running into no resistance that might guide you towards anything.

For me, it's not the blank page that terrifies me, it's the not being able to find the hill.

At the end of it all, assuming you've found your hill and made it all the way up there, there's a moment of release: the boulder is balancing precariously. While you know it's going to roll down the hill, making what you produces one more futile attempt to make a difference by shouting into an uncaring void, you know that you've made it.

The steeper the hill, the fiercer the struggle -- the steepest hill lead to the most gratifying moments, when you realize you have just achieved something you didn't feel was possible.

Over the course of the past two years, I had been working on a book about photographers and their fathers (including me and mine), and I just managed to finish it a little while ago in what felt like a gargantuan effort. There's no need to go into too many details (especially since the book doesn't even have a publisher, yet -- let's hope it will find one); but when it was done, I broke down and wept.

That can be writing for you.

Ever since I've finished the book, I haven't had much energy. It was as if a gigantic coil had released all of its energy. I found myself on the plain again. That wide, wide plain.

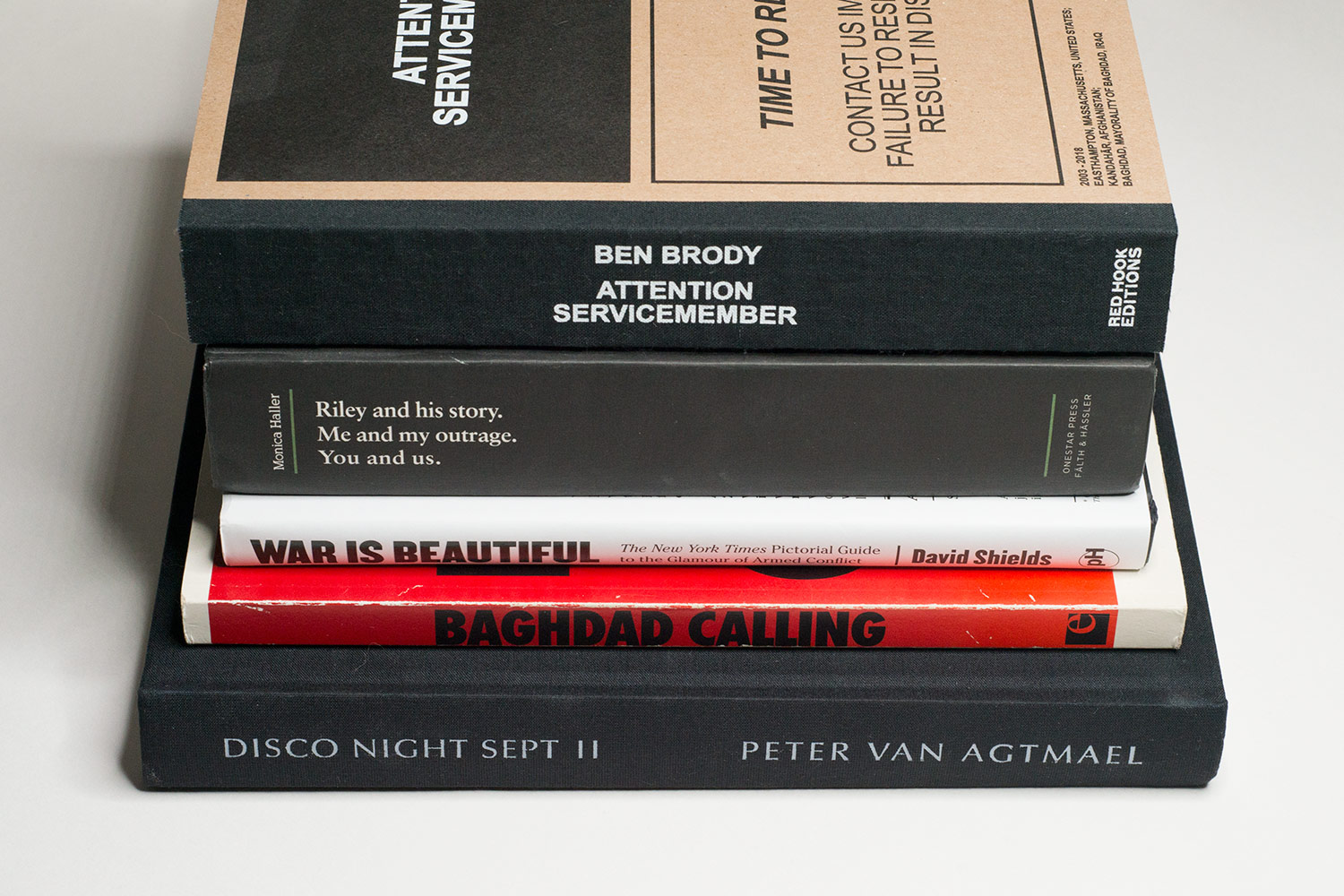

Maybe today I'll just note that I did find the energy to write a longer piece for my site about the best war photography books to have come out of the past 20 years. I could have added a lot of details in a lot of different spots. But there wasn't the time to do so. Plus, I don't think that long pieces are actually being read online. When there's a long piece I really want to read online, I print it out and read it on paper. I can't stare at a computer screen for a long time to read.

Also, war photography is such a thankless topic to write about, given how toxic the discourse easily gets when you dare to point out certain things. It's comparable to writing about street photography: some people have very strong opinions and feel very entitled. I mean mention the topic of consent in any conversation about street photography, and be prepared for an onslaught of extremely aggressive posturing by mostly older, male white guys. I just don't need that any longer in my life, especially since I don't care much about street photography in the first place. War photography... well, it's not interesting, either, but at least it touches on a larger topic that we're all connected to.

Instead of discussing all that's just not working in war photography, I decided I would only write about those books that have driven the conversation forward. That did the trick for me. I hope you'll decide to read it. Some of the books can still be bought, so maybe order one to learn more about the wars of the past 20 years.

I have been offering mentoring for photographers for 10 months now. I thought I'd mention this here. In a nutshell, I work with photographers on whatever they might need, typically the development of a project (or book). If you click on the image above or on this link you'll see a broad outline.

My mentoring is based on the experience of teaching at an MFA level for a decade. There, I worked with around 10 students every year on their projects.

It's all done online. Wherever you are, we can meet up over Zoom and talk about your work. If this sounds like something you might be interested in send me a note, and we can talk!

Seeing the picture I used in the ad above now had me realize yet again how much I miss traveling. The reality is that we could be back to some form of normal in the pandemic, given there are vaccines... Yet here we are, surrounded by antivaxxers and far-right politicians/news organizations who are single-handedly prolonging the pandemic. The most recent stories from the US talk of people taking horse-deworming medication instead of getting vaccinated (no, I'm not making this up).

I've basically resigned myself to another severe Covid winter, another full year spent without getting out of this country. I can't tell you how frustrated I am about this.

More and more, I've been noticing people being outright giddy when someone influential who had advocated against vaccinations dies from Covid. Even though I understand where that giddiness is coming from -- I'm German, and Schadenfreude is a word from the language I grew up with/in, I honestly can't and don't feel that way.

However difficult these times are for people who are trying to embrace compassion and empathy, maybe it's the difficulty that teaches the real lesson. If compassion and empathy were cheap emotions, as easily applied as a Hallmark card is sent, what good would they be? A while ago, I read a quote by a Buddhist monk. Unfortunately, I don't remember where, and I also don't remember the monk's name. The quote ran along the lines of "You don't feel compassion, you are compassion." I know that I'm not compassion, yet, and maybe I'll never be. Still, it's something I'd like to strive for.

With that: as always thank you for reading! Stay safe and well!

-- Jörg