Eastern European dentistry

About a month ago, I started something a little bit different. I decided that every day, I would take at least one photograph in my immediate surroundings — regardless of how inspired I’m feeling. If there’s more than one picture, I have to commit to one and put the others aside. I print that picture and put it on top of the growing pile of daily pictures.

The printing has as much to do with committing to the picture as with showing myself that I can do this exercise and that, hopefully, with time there will arrive a sense of accomplishment (even if it’s just seeing that I can follow through with my commitment to try to improve my photography and — maybe — love photography again more unconditionally than I do right now).

If you have experience with not feeling inspired photographically, you know that having too many pictures isn’t a problem. On most days, I have to force myself to do the work, which often means picking up my camera right after work has ended.

It’s not the most joyful exercise. So far, I have already made a few photographs I like, including a small number of photographs that I have not taken before. I obviously could take the kind of picture I know how to make every day, but I’m trying hard not to do it (on days when I’m especially tired and deflated from my work, I allow myself to do it).

I don’t quite know, yet, what will come out of this exercise. But that doesn’t matter to me.

These days, I tend to get up early in order to have time for myself before work starts. I used to not be a morning person. But I realized that a bit of time before work is worth more than any amount of time after, when I’ll be tired (at best).

Usually, I’ll take care of the cats and make myself a cup of tea. I’ll sit at the kitchen table and look out over the field in front of the house — towards the river, which is hidden behind a line of trees. The sun rises in that direction, and I never know what scene I will be presented with.

The other day, I decided that instead of drinking tea and attending to a notebook I had started filling with doodles, thoughts, and all kinds of other things, I would spend my time writing an article. So I did.

My articles are typically produced in a number of iterations. Unless I’m working on a commissioned, longer piece, I try to produce complete first drafts. Even if details are still in need of work, I want to see the full arc of the piece.

I once read that Tina Brown described working this way as writing “vomit drafts”. It’s an ugly picture for something that in my experience has a lot of value. If you think too much, you might stand in the way of your own writing. Well, I do anyway.

Of course, there is the editing part. Writing is editing. Or rather, it’s when you edit that you really improve your writing.

How do you edit, though?

I now don’t remember the source, but a little while ago, I read something along the lines of “you write the first draft for yourself, and you edit it for your readers”. Something to that effect. I found that idea enormously helpful, because even though as a writer you want to be true to yourself, in the end the reader will have to be able to follow and understand you.

I then realized how as a photographer, you can adopt at least part of that sentiment, especially when you make a book. If you think about a sequence of photographs, they have to make sense for a viewer. You have to edit your sequence with your viewers in mind, which typically are people who don’t know all the details that you know about your pictures.

In my experience, this is one of the biggest challenges for photographers: they often assume that a viewer knows as much as they do or that a viewer will also focus on that impossibly small and irrelevant detail in some picture. But you can’t do that because that’s not how it works.

Always edit for your viewers!

That essay, though — I realized that were I to edit it for readers, there might not be enough in it.

You always have to write for yourself, even if there is nothing of value for future readers. What has no value does not need to be put into the world.

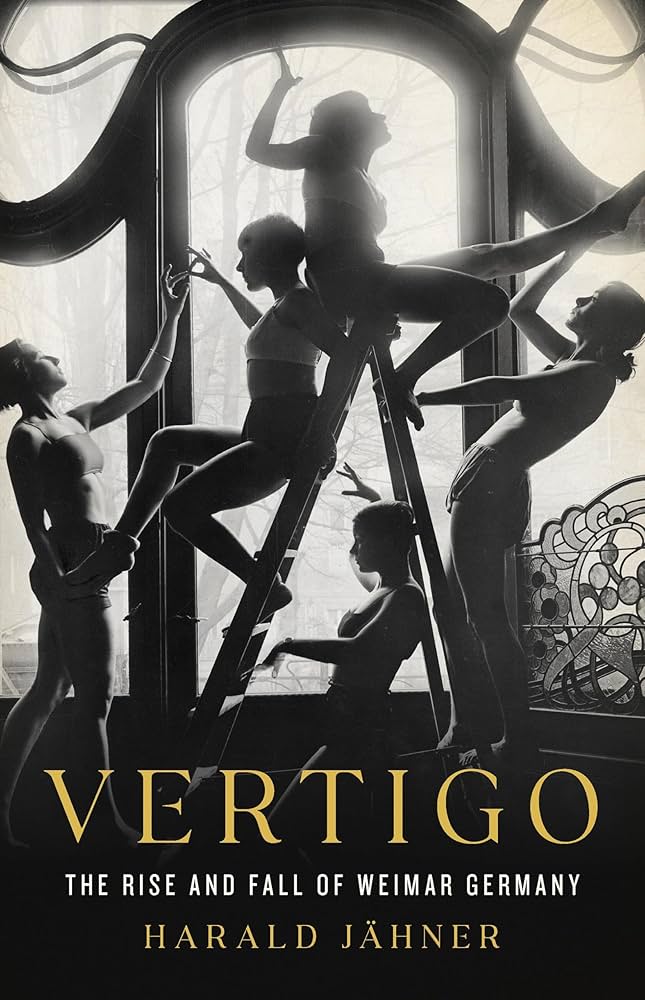

Links: A relatively recent book about the Weimar Republic has now been translated into English, Vertigo by Harald Jähner. I read it in German when it came out, and I can only recommend it. Instead of focusing only on politics and the succession of governments, it’s a much wider view, and it is richly illustrated. Here is a review of the book.

It’s a book you want to read, especially if all you know is the TV show Babylon Berlin, which pretends to be a truthful depiction of the era but in reality is merely entertaining kitsch. If you don’t trust me on Vertigo, here’s an excerpt from it.

There was an article by Oliver Koerner von Gustorf in a German art magazine that struck a chord with me. You will have to run it through machine translation if you are unable to read German. It’s worth the effort.

I don’t agree with all of its sentiments. But its depictions of the art scene as a neoliberal hell, filled with people who pretend to have the correct attitude while being at least co-responsible for what the art they admire attempts to deal with… That’s spot on.

Jonas Feige pointed me to an article by Charlie Engman about AI (thank you, Jonas!). It’s not that easy to come across AI article that dig deeper, and this one does. Even as Engman almost comes to the conclusion he works so hard for only to take the wrong turn after all, it’s a good read.

If you’re able to speak more than one language with confidence and competence, inevitably you will notice how they inhabit different spaces in your head. Or rather, you feel that you inhabit different spaces inside their worlds. Certain things can be said more properly in one language — at least it feels that way.

Sayantani Dasgupta writes about all of that in the context of someone who grew into three languages:

My husband tells me, “You are a nicer person in Hindi than you are in English.”

I’m certain that I am a nicer person in English than in German (I don’t think it would be possible for anyone achieving this the other way around). And if I ever manage to speak Japanese with confidence and competence, I think I’ll be a nicer person in Japanese than in English, given that Japanese uniquely incorporates social relations to such a huge extent.

Lastly, a very long and incredibly fascinating essay by Jacob Mikanowski about aspects of his family’s Eastern European past as they expressed themselves through his grandmother’s dentistry.

And with that I will have to conclude for today. After all, I still have to take today’s picture.

As always thank you for reading!

— Jörg