World full of strange tools

The other day, Alexandra Deschamps-Sonsino kindly invited me over to her Internet of Things London meetup to give a short talk. This is a written version of what I discussed. It's a really great meetup, and the way IoT is talked about in the discussions there reflects what I've been thinking about lately.

I vibe-coded a perfect back-scratcher

I'm a mediocre to intermediate coder. I'm comfortable and fluent in mainstream front-end frameworks like React and NextJS, and I can hit APIs and handle async responses properly. But I'm not good enough to write and publish a library that could meaningfully contribute to the open-source community. While I can build the things I need by stacking various technologies, I can't express myself in code as freely as I'd like. You get the idea – I'm more of a designer after all, and I think in terms of interaction and experience languages more than computational ones.

To some extent, Cursor changed that. Earlier this year, after reflecting on some emotions and experiences around how my name has been pronounced (you can read more about it here if you're interested), I built Nē-mu. I designed about 80% of the UI in Figma before moving to Cursor where I vibe-coded. I asked Cursor to handle form input correctly, to parse the list of languages Google's text-to-speech API supports, to load MDX so I could easily write the about page, and so on. After a couple of back and forths pointing out errors and giving some final manual touches, it was done in a day.

Like many have already said about AI-assisted coding, I could have achieved the same result, but it would have taken me significantly more time. And, also like many have said, vibe-coding is much more appropriate for throwaway weekend projects like this one than for serious, production-ready coding.

Nē-mu is precisely that kind of throwaway product. It's not a groundbreaking tool; it's a simple interface to two APIs. It's just a cute little thing that's more useful for me than for anyone else. Some of you might find it useful too, but chances are you're never going to visit it again. It has the silhouette and aesthetics of a product, but little real-world utility. It functions more as my personal statement on how names from non-Western cultures are pronounced in English-speaking cultures. I built it for myself.

Still, it was a liberating experience – like I'd crafted a special stick to scratch an itch on my back, perfectly curved to fit my posture. I felt like I'd gained a means to express my small desires in the form of a digital product.

Are we making Chindōgu?

Now, if I look at the community section of Lovable, where users showcase what they've "shipped" with it, I can find some projects similar to Nē-mu.

There's a world clock displaying the current positions of the sun and moon with the gradient of the sky in various world cities. An interactive ring size calculator/chart/converter thing. A mesh gradient generator. Regardless of whether the users can code, they didn't write a single line of code to create these products.

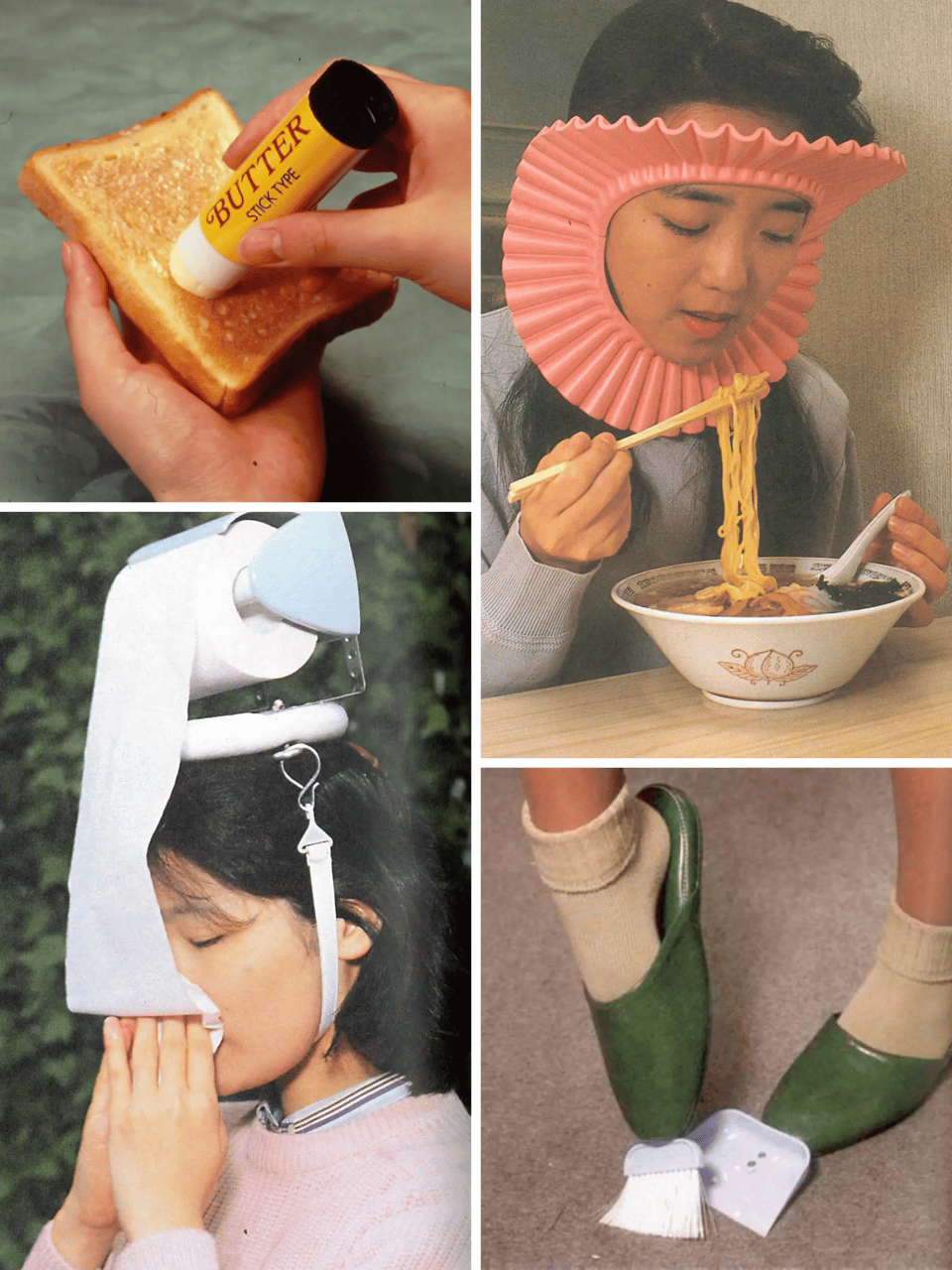

The nature of these tools reminds me of Chindōgu, a Japanese term that was briefly popular during the speculative design hype of the 2010s. It translates as "Strange Tools": Chin (珍: strange, weird) • Dōgu (道具: tools). This was a name given by Kenji Kawakami to a series of objects he created for spare pages in a magazine he edited in the 1990s.

Chindōgu look like objects from TBD Catalog by Near Future Laboratory, but they're more rooted in the everyday of their time, without advanced technologies. They're tools whose raison d'être you can grasp at a glance, and ones that we could make with today's technology, but somehow we haven't. They don't hold any commercial value. Their value, to me, lies in the way they make us question why we don't have objects like them around us. They're jokey and clearly made with a great sense of humour, but it's also clear that humour isn't the primary purpose of making them. They're born from super personal, extremely mundane motivations.

Perhaps one of the implications of the rise of vibe-coding might be that we start making strange but deeply personal, one-off tools, mostly to satisfy those immediate "itches and glitches" that mainstream tools cannot address.

In the IoT meetup, someone pointed out that there might be a parallel we can draw between vibe-coding and the rise, fall, and plateauing of the 3D printing culture. When 3D printing was in the middle of its hype, people were either super excited or genuinely worried about the prospect of everyone making throwaway plastic objects. 10+ years later, it seems to have found its own comfortable place in hobby, DIY, and maker cultures. Maybe vibe-coding will follow a similar route and become a niche way of making digital products. But you can also imagine a world where these two ways of making combine, with LLMs lowering the barrier for creating and customising 3D models. A world where making physical objects becomes more vibe-based.

What would it mean for us to have the ability to instantly materialise even our most mundane imaginations? How could we channel this power into challenging our assumptions and filling the gaps left by corporate production? What would a world full of Chindōgu look like?

"Chin" doesn't necessarily mean Good

I occasionally volunteer at a local Repair Café. And if someone brings in an old, long-discontinued hand-mixer or something and we could model and print a spare part on the fly, just by filming the broken part of it with some supplementary info, that'd be amazing. Or some community or school events might benefit from local, niche, and quick digital/physical making. The very experience of making something for ourselves can sometimes empower the community too.

The idea of a life surrounded by Chindōgu is a fun one to entertain. But that doesn't mean I blindly celebrate the way vibe-coding works under its current arrangement. The energy and water consumption of AI-assisted coding might not be as high as some of us feared, but most of these tools help consolidate power into the hands of only a few companies who build popular foundation models. The over-reliance on them might, in the long term, take away from coders the very ability to challenge this power dynamic.

Also, when I picked some example products from Lovable's website, I really had to carefully hand-select ones that fit the theme, and the fact that there are multiple crypto investment dashboards was depressing. While I do believe that we can vibe-code or vibe-make niche tools that invite people to challenge the status quo and serve people left behind by mainstream solutions, the vast majority of what people make isn't geared towards that and possibly is never going to be.

I guess I'll keep exploring the implications of this new way of making cautiously.