This letter was published yesterday in 100 Days of Creative Resistance, a project organized by the writer Brian Gresko, who kindly invited me to contribute. It’s been wonderful receiving a missive from so many fantastic writers each morning; if you’re interested, I encourage you to sign up. Honored to have had the opportunity, and also grateful for the nudge back to newslettering here.

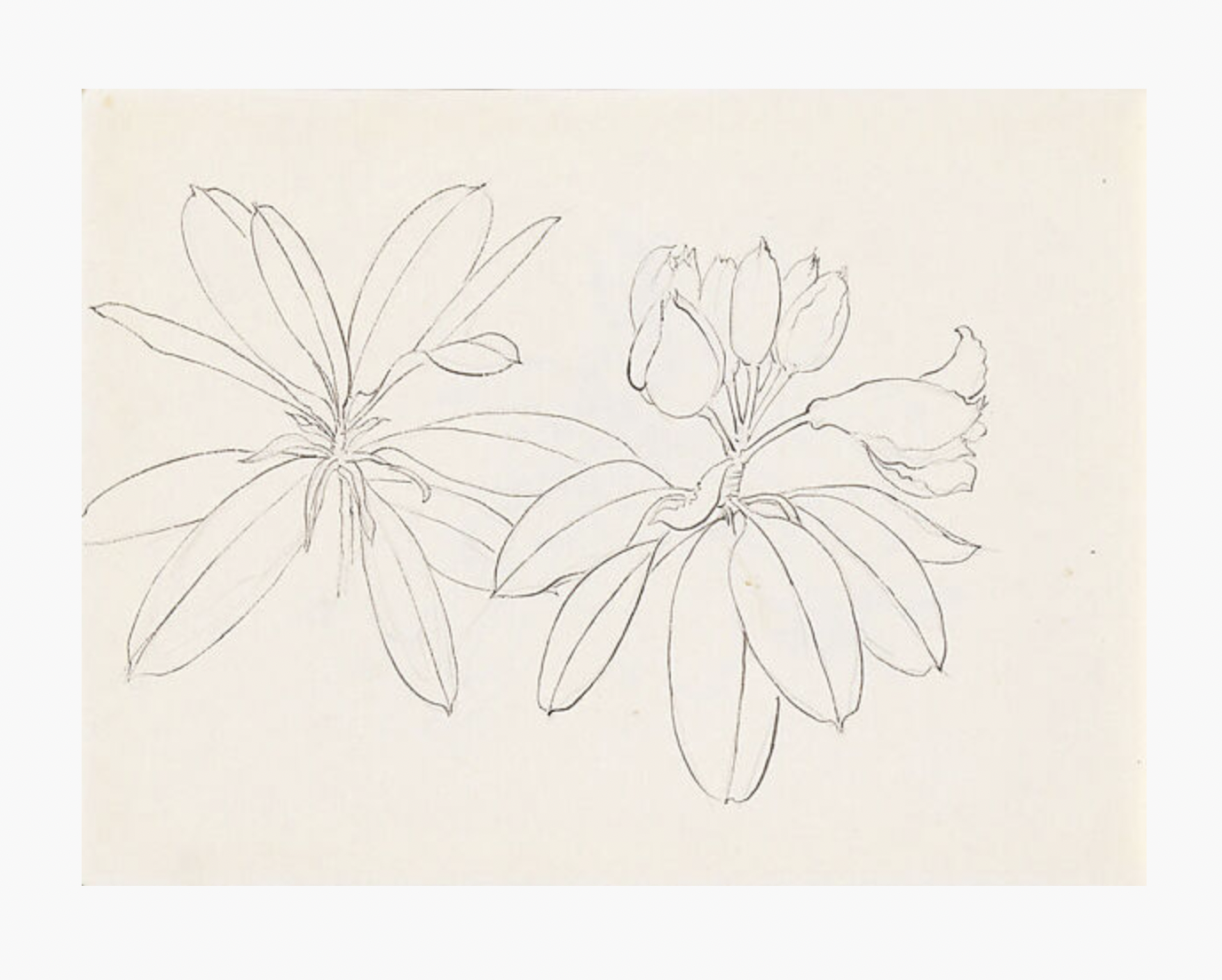

I live in a house with two enormous rhododendron bushes planted on its east face. One I can see from the kitchen window; the other from the living room. Here is how little I know: at the beginning of winter, after the leaves of all the other trees had dropped, I turned to my partner and asked, do you know if rhododendrons keep their leaves?

The answer is that they do. The other answer, which I learned from my neighbor, whom I met while we were both shoveling snow: you can tell if the temperature is below freezing by whether the leaves of the rhododendron are flat or curled. The tighter the curl, the colder the air. This morning the rhododendron leaves are curled tight as pencils. It’s thirteen degrees outside.

I deleted all social media off my phone at the beginning of the year—Instagram, which I was more or less addicted to, and Reddit, where I only ever lurked but was addicted to scrolling as well. I did this because I had known for some time, maybe years, that Instagram made me feel anxious and sick; that I did not handle well the shock of algorithmic, high-temperature, attention-grabbing information that appeared unexpectedly every time I pulled my screen down with my thumb, though I kept pulling; and that this feeling would not grow better but worse.

The last time Trump took office, I was working a day job at an anti-violence nonprofit, serving a demographic that was being attacked by the administration in basically every way: immigrants, queer and trans people, survivors of intimate partner violence. My job was to monitor the news and write messaging for our community; every morning, I sat at my desk, aghast, as the latest leaked executive orders splashed into my inbox. The cruelty is the point, we were fond of saying then—imagine being fond of such a phrase, but we Tweeted it. The onslaught was the point, too. To barrage us into submission.

Last weekend, I went to a training for volunteers who will work with patients in hospice. I will have a few more weekends of training later this spring. I have been calling this, loosely, my death doula training, but in reality I’m not receiving a certification from this program; I’m only hoping to become qualified enough to sit with people at the end of their lives. Though you already know there is no qualification for this. Anyway, what I want to tell you about is a term that the facilitator, Roy Remer, shared with us, which is empathic distress. Empathic distress is what happens when we witness suffering in others, in the world; it is an involuntary, immediate response, and it is only alleviated when we are able to help others—when we are able to turn that empathy into compassion.

Empathic distress is real, Remer told us; it has physical effects, it will make you sick. When we’re locked in this state, we want to retreat, to numb ourselves to protect ourselves from these negative feelings. Empathic distress blunts us. Over time, we lose our capacity for joy and pleasure. (Does this sound familiar?) Yet there are hundreds, thousands of times in our lives when we will witness suffering and have no outlet, when we will be caught in the loop of our empathic distress. What then?

Self-compassion, Remer said; I believe him. When compassionate action is unavailable or indistinct, when we are too far to touch or driving past a highway accident or someone we love is dying and we cannot do anything about it—we must offer ourselves self-compassion. We listen to the one who is injured, who cries out at the suffering of others, and we take care of that one. When we tend to ourselves, we lift the loop of empathic distress. We take it off our shoulders, and we open again to the world.

This isn’t a call to turn away from life or its suffering. Instead, I think of it as a way to situate ourselves more fully and bodily in the world. In a time of constant bombardment, of overwhelm and attack, where are moments when we do feel that pull—that call to help others—and can actually listen to it, instead of blunting it, shoving it away? Where can we put our bodies in rooms, our hands to work, our hearts to deep listening? No matter where you live, there’s probably a place that would love to have you help. I’ve found volunteering in-person incredibly grounding. I go to my local food pantry, which serves many displaced and immigrant families; the need is immense. I cannot change anyone’s life. But I can hand someone vegetables, say hello, ask how many onions they want.

I began this letter with the rhododendron because I wanted to tell you something about listening to the body. To getting to know what is close and particular: neighbors, plants, people. Self included. Where can you commit your time? Where can you practice compassion in the world?

I have been trying to use my phone less, to keep it outside of the bedroom, so that its screen will not be the first thing I touch when I wake. I am grateful I don’t need it to check the temperature. I fill my glass of water at the kitchen sink and look for the leaves of the rhododendrons.

Till soon,

LP

I’m still figuring out the cadence of writing here, let alone a paywall, but I hope to be sending letters more often now that I’m off social media. Paid subscriptions have been turned off since the start of Yield Guide’s hiatus last year, but if you’ve been charged or would like a refund, please email me and let me know!

You just read issue #17 of YIELD GUIDE. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: