While I was home in December, I badgered my parents into telling me about the meaning of my Vietnamese name. My Vietnamese name is a variation of my mom’s; the first character is the same, but the second differs. I’ve always known what the first meant, but even my parents have admitted that the second half of my name is harder to explain. The second part of my name is Trang. I wanted to know what it was, what it meant.

It’s a manner of being, my dad explained. A kind of elegance. A nature you carry with you. That’s too abstract, I said. It’s hard to translate in English, he said. Why did you give me such a complicated name, I said. I say this more often than I would like, especially whenever I have to fill out any kind of government paperwork because my full name never fits. I was beginning to grumble. I was growing frustrated. It’s also, my dad said, a kind of flower.

Hoa trang, my mom said.

My heart leapt at this. That I could be a flower. That I already was, before knowing.

*

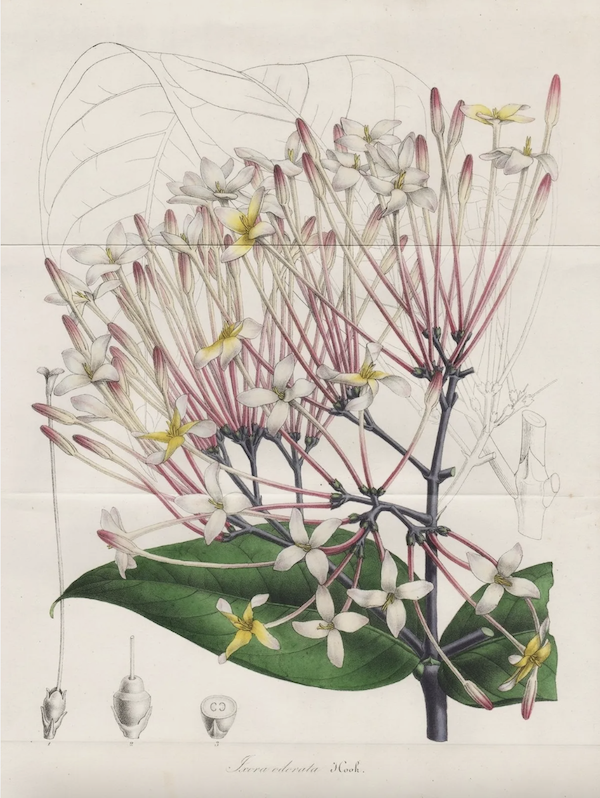

Ixora, also known as jungle flame and West Indian jasmine, is a small, evergreen shrub that produces profusions of small flowers. Each flower is four-petaled, tiny, sweet-smelling, the flowers growing in round, airy clusters akin to that of hydrangeas. The leaves are leathery and deep green. The flowers are most often white or red. White ixora, in Vietnamese, is hoa trang trắng. Red ixora is hoa trang đỏ. All the sources online tell me that it is rare. If I have seen ixora before, I have not known what it was called. I cannot tell you what it smells like, or what the leaves feel like in one’s hand.

*

I spend two, sometimes three mornings each week at a Zen temple. I wake at 5 a.m. and am seated in the zendo before sunrise. On the monastic schedule, there are two periods of meditation, then service, temple cleaning, and breakfast; all of this takes place before 9 a.m. After breakfast is study, my favorite part of the day. For one hour, all you have to do is read. Lately, during study, I’ve been reading Thích Nhất Hạnh’s journals, from 1962-1966. Written while he was a student and teaching assistant at Princeton and Columbia, in the journals he recalls the process of beginning an experimental monastic community in the forests of the central highlands of Vietnam. The temple, set deep within the forest, was called Phương Bối, or “Fragrant Palm Leaves.”

It’s deeply moving to read Thầy’s journals from this time—Phương Bối was started in 1958, and the rural setting and the embrace of the forest offered the young monastics a setting of peace and serenity amid a time of political turmoil and increasing suppression and censorship. There’s a sweetness to the writing, reading his descriptions of building simple wooden structures, the Vietnamese students’ interactions with the indigenous Montagnards, and the efforts they made to create a safe and caring home for their practice. And as I read, at the bottom of one page, I noticed something—my name.

“One afternoon, as Hung and I stood on the balcony looking down at Meditation Forest, we saw a cloud stretching like an unfurled bolt of silk from the forest’s edge to the foot of Montagnard Hill. We ran down the hill to stand next to the cloud, but it disappeared. So we climbed back up the hill, and there it was again! Filled with pines and other majestic trees, Meditation Forest was the most beautiful part of the forest. Our plan was to make narrow walking paths and also a few places where one could sit in meditation or quiet reflection. There were many varieties of flowers for us to pick for the Buddha’s altar, but our favorites were the chieu and trang blossoms.”

How incredible that I encountered that sentence, just weeks after talking to my parents, making these flowers, my namesake, real to me. I still don’t know if I’ve ever seen them—I must hope that I have. But how incredible that Thầy had picked them for the altar, that they grew in that very same forest. I almost never see my American name in writing, certainly never on the keychains on Canal Street. But I saw my Vietnamese name, there. On the page. In history. In a life.

I’ve been thinking about peace, and protest, and the need—if there is a need—for revolutionary violence. And I have been thinking about my own search for answers, how I want someone to tell me what to do and what is right. Thầy was a lifelong activist for peace; it was what led to his exile from Vietnam until he finally returned, after a stroke, in 2018. But my own grandparents—I write about this often, but it’s because it is so important, and so beguiling, and so impossible for me to imagine—met as part of a revolutionary army in 1945. It wasn’t merely through protest or diplomacy that French colonization in Vietnam came to an end; it was as the result of a siege, and a battle, and that battle one of many within a war.

The other day, I looked around online to see what Thầy might have said about Palestine. In 2003, he gave a talk at Plum Village during a retreat for Palestinians and Israelis intended to bring about greater understanding. He encouraged young people to choose peace, to not join violent revolution. “The war machine is horrible,” he said. “If you get into it, you will be crushed, and you will have to crush the lives of others.” What he proposed—and it makes me want to weep to think of how earnestly he must have proposed this, how much he must have believed in it—was to write a letter.

“Sit down together and write a love letter,” he said. “The letter must be the product of your understanding and compassion. If you don’t have enough understanding, you cannot write the letter. The letter may take several months, because you want to manifest all the awakening and compassion that you have in your heart. When you have finished the letter and the other group reads it, they will see that you wrote it out of your awakening and compassion and that it is not just diplomatic. That will move their hearts.”

What I want to know is, can that really be true? Can a letter move someone’s heart? Can compassion move somebody’s heart?

It’s been over a hundred and thirty days of unceasing violence against the people of Gaza. Over 28,000 Palestinians have been killed; thousands more have been maimed, and thousands buried under the rubble from bombings. As I write this, the Israeli army is preparing a ground offensive in Rafah, a so-called safe zone they had previously directed Gazans to retreat to. More than two million Palestinians have been displaced from their homes. Rafah is now the most densely populated area in the world, already under attack from airstrikes, and the Palestinian people have nowhere else to go.

I know there have been protests. I know there have been fasts. I know there have been strikes. I have been in the streets, held up my sign, called my reps, emailed and faxed, striked, signed open letters; I have been, as you have been, a witness. And I have tried to act. What I want to know is—when will hearts be moved? It feels as though we’re living in an alternate reality from that of elected officials, the U.S. government, and the mainstream media. When constituents are overwhelmingly calling for a ceasefire yet only sixty-six members of congress—and only five senators among them—have signed onto the resolution. When the New York Times and other media institutions continue to hem and haw in their reporting on the genocide in Gaza while the Israeli army continues to target and murder journalists in Palestine. There have been so many dead children. There have been so many dead. What does it take? What will it take? When will the violence end?

I don’t have an answer, not for this. I will keep making the efforts I have been making. I mean to tell you that I am moved, and I hope you are moved, and that what we are feeling is real, including the grief and the alienation. And what we believe in is real, and what the Palestinian people want—and deserve, and have been martyred for—is real, and that the real must win over the unreal, even if I cannot tell you how.

*

All of our liberation is entwined with each others’. We need more than a ceasefire; we need the total upheaval of the order that keeps the oppressed oppressed and disenfranchised and hungry. This is a global change, a world-shifting change, a radical transformation. It will take steady work in large and small ways; it will take the entire dismantling of the American state as we know it. I know that we are ready. I know that we want it. We begin, maybe, by caring for each other. By undoing the racism and patriarchy and ableism grown into our communities and systems like vines. Already that is a life’s work, that undoing. But I believe in it. And it, too, is real.

When I learned what ixora looks like, I felt as though I had known it my whole life. The small white fragrant flowers. I imagine it must be visible at night. That the insects come to it, and the birds. The hummingbirds with their long, curling tongues. I imagine that it glows in the moonlight, and that the flowers, when they bloom, are closed, shut tight for what feels like decades, and then open all at once.

Till soon,

LP

Some links to actions you can take: You can donate to the International Federation for Journalists’ safety fund (write “PJS-2023” in the comment box) to help purchase safety supplies for journalists in Palestine. You can write to your representatives using democracy.io, and if you can, call and fax them too. You can read reporting from places like Al-Jazeera and Democracy Now. You can participate in a strategic consumer boycott as part of the BDS movement, and if you work at a cultural institution, you can sign onto PACBI. There are so many of us. We are in this together. Free Palestine.

You just read issue #14 of YIELD GUIDE. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: