good life / good death

the way we’re supposed to go, the way we’re not supposed to go.

I read the text from my mum last night after waking up groggy from an evening nap that I should really have taken much earlier in the day. My paternal grandfather—my Yeye—died at 6:04pm.

It wasn’t a shock or a surprise. He was around 90 years old. He’d been deteriorating for quite some time, with stints in intensive care and months in hospital in Shanghai, the city in which he spent most of his life. In recent weeks, it sounded as if he was mainly getting palliative care. Yesterday morning, my dad, based in Tianjin these days, heard from the hospital that time was running out. There were no flights available, so he got on a bullet train from Beijing to Shanghai.

Losing Yeye is a strange feeling; there’s a sadness that seeps out from within, but it’s a sadness with no clear anchor. It just settles on my skin, like an oil slick.

Unlike my maternal grandfather, who sat near the top of my list of favourite people in the whole wide world, I barely knew Yeye. Growing up in Singapore, we rarely saw him. I only have blurry memories: of meeting in hotel lobbies when he was in town, of visiting him in Hong Kong where he lived for over a decade, of seeing him in Shanghai or Beijing during the school holidays when my family wanted to experience cold winters. I don’t think we ever had a proper conversation beyond the usual greetings and pleasantries; I remember being a little intimidated by him as a child. I don’t remember much in the way of affection. I have some vague impression of hearing that he could be strict and he had a temper, so I think I was wary of triggering that somehow. But it wasn’t like there was bad blood; just distance.

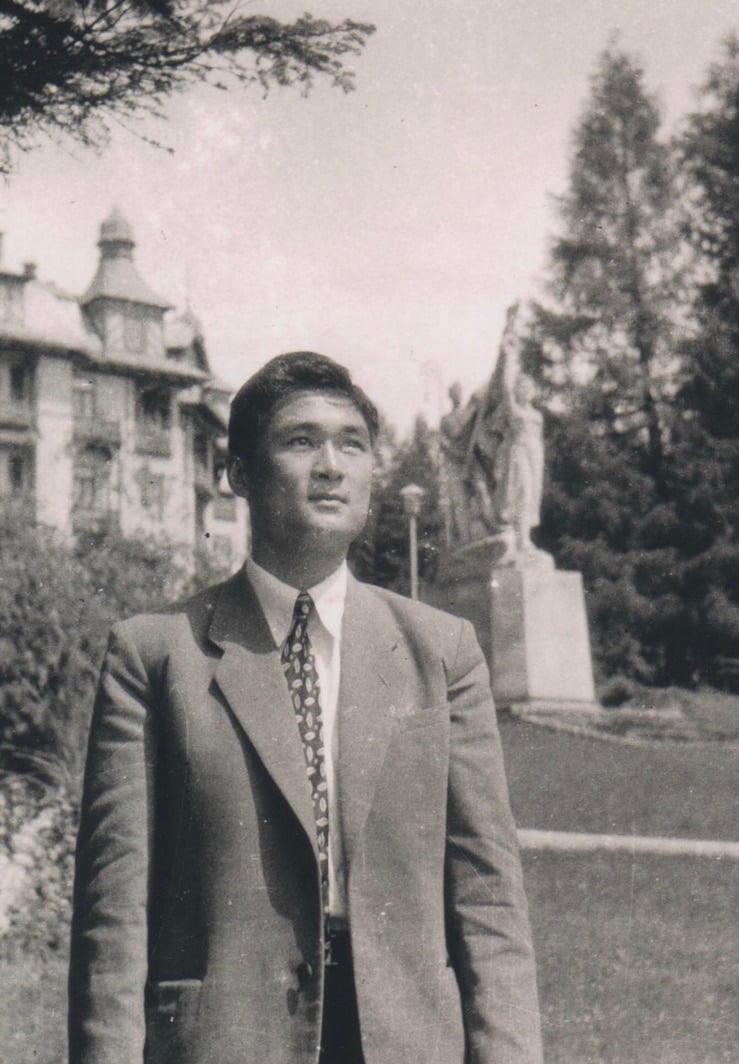

What I remember the most clearly about Yeye is his square jaw—softened a little in my dad’s rounder face, but copy-pasted on to my uncle—and his low, gravelly voice that, in today’s content creation world, would have been perfect for ASMR. He smelt of cigarettes; you’d think that someone who played the French horn for a living would be much more protective of his respiratory system, but he was a chronic chainsmoker. My dad used to buy cartons of cigarettes at the airport duty-free during our trips to China, because Yeye could burn his way through multiple packs a day. I don’t know if this changed later, but I’ve joked that, for much of his life, probably the only time he wasn’t smoking was when he had a horn in his hands.

It only sank in just how little I knew about Yeye when my dad, brother and I went to Hainan—Yeye was born in Wenchang on the island—for his 80th birthday celebration in 2014. I’d been expecting a mildly extravagant but still homey birthday bash consisting of extended family and Yeye’s many horn students from over the years. Instead, we were whisked out of the airport and straight to a press conference at the library in Haikou, where what I’d understood to be a homemade scrapbook of family memories that my uncle was putting together turned out to be a proper coffee-table tome, presented to the library in commemoration of Yeye’s birthday and his 60 years of contribution to the world of French horn. The “little recital” my dad said Yeye’s students were putting on was actually a 90-minute concert. I sat near the back of the auditorium; there were television cameras behind me.

I’ve found a bit of the media coverage of the occasion:

On March 1, Chinese horn master and educator, Professor HAN Xianguang, celebrated his 80th birthday, together with his 60 years of contributions to the horn world. The first event took place at Haikou, Hainan Library titled "Nostalgic Music of Universal Love"—International Horn Master Concert, with world-class horn players and musicians. This was also one of the Tianya community's 15th anniversary celebration series. Besides Hainan-born horn master HAN Xianguang and his horn-playing sons, HAN Xiaoguang and HAN Xiaoming, were other major performers, including Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz Principal Horn GU Cong, Chinese National Grand Theatre Orchestra Concertmaster YANG Xiaoyu, and Chinese National Grand Theatre Orchestra cello soloist AN Rui, together with well-known Chinese musicians from the mainland and abroad. The performers and programs were rich and interesting, the Hainan audience was lucky to have such a rare treat with a night of world-class classical music performances.

On that trip, I discovered that Yeye had been the first horn student, then teacher, at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. He joined the conservatory after passing an audition as a teenager in 1951. He was the first Chinese horn player to win an international competition, and taught many players—including my father and uncle—who later struck out and made their own impact in China and beyond.

This was a big deal, and I only found out when I was almost 26 years old. I’ve told this story quite a lot to various people because, even though I’m not close to Yeye and have contributed nothing to the great horn tradition, I’m proud of this family history. Yeye took on the French horn at a time when there were no other horn students at the conservatory level in China; his first teacher was actually a trumpet player. It’s a reminder that I come from people who were willing to stray from tried-and-tested paths, work hard, roll with the punches, and make a difference in some way.

I don’t know what Yeye’s final moments were like. I’m not sure how conscious he’d been over the past few weeks and months. I hope he was as comfortable as he could have been, and that he left this world as peacefully and painlessly as possible. I’m not sure I can say I’ll miss him, since we barely interacted and there are so few memories, but there’s a sense of loss nonetheless.

I have a little video of Yeye that my dad sent during Christmastime in 2020. He’s playing ‘Jingle Bells’ with a little girl (I forget if my dad ever told me who that was), both of them on French horns while a pianist provides accompaniment out-of-frame. More specifically: he’s playing ‘Jingle Bells’ with a little girl while dressed as Santa Claus, red-and-white suit, hat and belt, a white beard fastened to his head with white string or elastic band. On his feet are cosy-looking plush slippers. It’s festive and sweet. I have no idea how often he was cute and whimsical like this, but I’m glad I have this one glimpse, at least, and it’s something I can hold on to as a remembrance.

There’s a lot about Yeye that I cannot speak to, but I think I can say he lived a full life. He had his adventures and achievements, and made his mark on the world. In 1962, he was the first performer of Fantasy-Concerto <In Memory>—composed by Shi Yongkang, a former professor of composition at the Shanghai Conservatory, who wrote it for, and dedicated it to, Yeye—the only surviving horn concerto from the era before the Cultural Revolution. I don’t know if he had any regrets, but he’s had his share of triumphs and he’ll be remembered.

I’m going to a vigil tonight. Not for Yeye, but for Datchinamurthy Kataiah, a death row prisoner whose execution has been scheduled for Thursday (the same day Yeye will be cremated). Datch has been on death row since 2015 and is 39 years old. He was arrested in 2011 and later convicted of trafficking almost 45g of heroin. The death penalty for an offence like Datch’s doesn’t meet the international standard that says that capital punishment, if retained, should only be used for “most serious crimes”, understood to mean intentional killing. By imposing the mandatory death penalty on non-violent drug offences, Singapore doesn’t just break from the global trend away from the capital punishment—it spits in the face of international law.

Datch has fought long and hard for himself and other death row prisoners, representing them in legal applications when no lawyer could be found to take on the case. He has been braver and stronger than I’ll ever be able to fully comprehend. He is brilliant, cares for his friends, and is clearly not beyond redemption. There’s still so much potential, so much he could do, if only the state would give him a chance. But it won’t, and, barring an absolute miracle, Datch will be killed on Thursday morning.

My grief for my grandfather sits on my skin; my grief for Datch pierces and burrows deep into my chest. My grief for my grandfather is tinged with the consolation of a life well-lived; my grief for Datch burns with anger at the blatant cruelty and injustice. This is not how a life should end—judged by privilege, condemned by power, violently taken by public servants. I can accept that it was Yeye’s time; I cannot accept that it is Datch’s.

There will be more after Datch. Many on death row are at imminent risk of execution. There are prisoners and families now living in fear and dread every day, terrified of phone calls and letter deliveries. It’s a trauma that is fully, deliberately, man-made. It’s a trauma that no one should ever have to experience. But so, so many already have—some, like Datch and Pannir, more than once.

This weekend I will attend the official launch of Death Row Literature: A Collection of Poems, by Pannir Selvam Pranthaman. Pannir is a prolific writer: of letters, of poems, of songs. During visits, he sings and raps for his little sister Angelia, making sure she commits the words and melodies and details to memory so she can communicate them to musicians and artistes back in Malaysia and have the songs professionally produced. Whether set to music or printed on the page, his words point to a person who’s proficient in multiple languages, who thinks and feels deeply, who reads widely, who is full of ideas. Who is full of life.

But Pannir could get an execution notice—it’ll be his third—any day now. And, after Pannir, more and more and more, with no end as long as Singapore chooses to wage this senseless, bloody war.

Both my grandfathers left us the way people should go: after long lives that, however imperfectly, were lived to the full. They made their mistakes and were given chances. It wasn’t always easy, but their life stories unfolded and developed to a natural conclusion.

This is a grace that capital punishment snatches away from everyone on death row. The regime torments in life and tortures in death. And still the human spirit struggles to prevail: in a message conveyed from prison, Datch said that, if his execution proceeds, he will hold his head high when he walks to the gallows. He’s not the one who should be ashamed. That shame shall lie solely with those who use their power to kill—the ones who deny others the good lives and good deaths they desire for themselves.