New music, Big Fiction, and some recommendations

Hello! You’re receiving this email because you signed up at some point in the recent or distant past for updates from Wm Henry Morris.

If this email arrives as an unwelcome surprise, click here to unsubscribe (or if that doesn’t work, scroll down and hit unsubscribe).

For everybody else: hey, it’s been awhile. When I decided to ditch Mailchimp (for, imo, unsavory data practices) and move to Buttondown, I got you all out of Mailchimp, but then never actually started sending emails.

Recently I’ve been wanting to share thoughts that are too long for social media and not quite long or formal enough to write an essay about for my website. So my intention is to channel all that into an email I send out on a (roughly) quarterly basis.

WHAT'S NEW

I wrote about near future science fiction for my personal website: On Reading Joanne McNeil’s Wrong Way as a Science Fiction Novel

I also wrote about the early reception to Tone: On Sofia Samtar and Kate Zambreno’s Tone and the word perplexing (there have been a couple of good things written about it since I posted this, but not a ton)

I released a new single (as Will Esplin) on Bandcamp that’s drone/dark ambient/cinematic: A Basin of Ink

More on the process behind creating A Basin of Ink below.

And if you haven’t seen this on social media: yes, I’m making music now. I’ll share a bit more about that journey in a future newsletter.

Now on to the main event…

ON BIG FICTION AND SF&F

Dan Sinykin’s Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Literature, which was published in October 2023, joins Mark McGurl’s The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing as two crucial texts, imo, for understanding the American fiction landscape of the past sixty years.

Like McGurl’s book, what’s important about Big Fiction is that the historical context is combined with analysis of works of fiction to show how the documented changes in the field impacted actual texts.

Most notable for me, I now better understand something that has bugged me for years: the meta-fictional turn Stephen King makes in his Dark Tower series (see Chapter 4).

I’m not going to summarize all of the arguments of the book here. Other than reading the book, the best way to approach it is this New Yorker article or, if you’d prefer audio, this LA Review of Books podcast.

Instead, I’m going to share what the book caused me to think about in relation to Science Fiction & Fantasy publishing in the United States. These observations/questions will not have the research behind them that Sinykin did and so are tentative, perhaps of further interest, and maybe even ham fisted. But here we go:

The switch from mass market paperback to trade paperback (which occurred for a number of reasons, but the big one is conglomeration—and not just among publishers, but also among distributors and retailers)—is probably the single most important change to the field of SF&F. I know there is some awareness of that in the field, but it deserves a book-length study, and especially one that does like Sinykin and not only recounts the history, but also analyzes specific authors/novels. Sinykin does cover this in the book (see esp. pages 58-62). In particular, conglomeration led to the rise of fantasy (over science fiction) and media tie-in novels. Fantasy novels were predictable. Could be written to formula. Were less likely to be controversial. Were perfect for Tolkien fans looking for more of the same, especially among middle class (mostly white) younger readers in the suburbs shopping at the newly arrived chain bookstores. But he’s mainly focused on top-selling novels/authors and I suspect that there’s a lot that happened in the strata below that is worth exploring (and explaining).

One of the results of conglomeration was the weakening (and often the closing or hollowing) of imprints that were a strong reflection of their editors individual taste. This was particularly devastating for ambitious literary fiction. It also affected SF&F. However, as Sinykin notes: “In science fiction, Betsy Wollheim held her own at DAW Books, David Hartwell at Tor, and Lou Anders at Pyr Books” (60). I know there’s work out there on the outsized impacts of certain editors on the field (especially Campbell), but it’d be interesting to take a look at how these three editors navigated the conglomeration that took place in the industry in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, and also do a study of the nature of the books they published in relation to other SF&F publishers/imprints during the same time. I also wonder how those three editors were able to hold on. Possibly because of their long tenure and entrenched power; possibly because of lower expectations for their imprints in relation to their corporate siblings (and enough massive hits to keep their bottom line looking good); possibly because the folks in charge of the corporate parent had fewer opinions on genre; possibly because they were more easily able to make concessions to the demands of conglomeration.

Publishing—and SF&F authors, readers, agents, and (I suspect) editors—have a love-hate relationship with trilogies and series even though conglomeration publishing really pushed for genre publishing to embrace them. This is a thread that has definitely continued on into the 21st century. It’d be interesting to take a look at that in relation to the conglomeration era. And especially in relation to specific texts themselves. I think such analysis would also need to bring in a parallel development, which is the post-Jaws/Star Wars blockbuster in Hollywood. Even more specifically: in what ways are The Two Towers and Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back models for the second book in a trilogy? Also: what do unfinished series (you know the names: Martin, Lynch, Rothfuss [but there many more; some of them due to the author’s resistance; some of them due to publishers dropping the author]) say about the publishing industry and about fiction as culture in the 21st century?

In Chapter 5, Sinykin charts the rise of nonprofit publishers and how them positioning themselves against New York publishing alongside the outside funding (grants, etc.) available to those publishers led to them positioning themselves as literary and diverse (150), and how those two words were defined (in grant proposals and also in the books they acquired), and how such positioning led to mixed feelings among the non-white authors they published. It’s both an inspiring and complicated part of the book, and it made me think of SF&F-focused small presses and where and how they position themselves in relation to the field. Aside from an analysis of this part of the field, I feel like, at the very least, need to make sure we document this history. It’s so easy with small presses that rely on one or two individuals to not only cease operation but simply disappear from our history.

Sinykin briefly nods at self-publishing towards the end of his book. While vats of ink have been spilled on whether self-publishing is something new authors should consider or not (and if so, all the opinions on the “best” or “right” way to self publish), I think there’s a lot of ground to cover that’s specific to SF&F. For example: the fanfic to self-publishing to trad published pipeline (not necessarily by a specific author, but in terms of sub-genres, tropes, and styles, with cozy fantasy and romantasy being the primary examples that come to mind). Or: which genres are over-represented and under-represented in self-publishing? Or: how did certain genres change as they moved from primarily big publishing to mostly self-publishing? (Grimdark and military SF come to mind here.)

There’s more, but I’ll stop here. As you can tell, I found Big Fiction to be a thought-provoking book. I’d love for more work to be done about this era, especially as it relates to SF&F. And if you know of articles/books/chapters of books that focus on how publishing conditions have impacted SF&F, I’d love to hear about them.

A final note on Big Fiction: literary fiction and science fiction suffered the most as the result of publishing conglomeration. The fact that the lit-fic/SF&F divide continues to suck up as much oxygen as it does is deeply ironic. If anything, all writers of some ambition—whatever it is—to contribute to the world of fiction should have solidarity with each other. The enemy is not each other. It’s the non-book people and the fake book people who leverage power and capital to define what gets published and work hard to maintain certain perceptions about publishing so they’ll have a continual supply of authors willing to mold themselves and their fiction into the type of product that conglomeration publishing demands.

To be sure, the state of publishing that existed prior to conglomeration was clubby, rather WASP-ish, and also problematic, especially in relation to women and people of color (whether they were authors or employees). But what Big Fiction makes clear is that not only was something lost due to conglomeration—fiction has been and continues to be warped by it.

This is not an indictment of any particular trad-published novel or author. There have been and continue to be a lot of excellent fiction coming out of the conglomerates (often in spite of). Rather, it’s a reminder that the conditions under which fiction is written, acquired, edited, marketed, and sold have an impact.

And now for something completely different…

ON WHAT I'VE LEARNED BY MAKING MUSIC WITH VIRTUAL MODULAR

What I’m going to try do here is talk about making music with virtual modular in a way that might be applicable to other hobbies/pursuits.

One of my ways of dealing with the pandemic—after spending the first few months mainlining Jane Austen and Edith Wharton audiobooks (love you librivox!)—was, like many folks, to pick up a hobby. I needed something that wasn’t reading, writing, or writing about fiction.

So in spite of almost no musical training, I started learning computer-centered music production. One of the things I love about it is that it involves technology, theory, storytelling, technique, performance, and more. There are so many aspects of it to learn, and a multitude of free resources to do so. It can be overwhelming, of course, but it’s very satisfying have an endless, varied well of stuff to explore.

And it’s been such a boon to my mental health and creative self.

LESSON ONE: I strongly recommend a hobby that uses a different part of your brain than your main vocation/hobby/work, especially if you’re a writer or editor.

This is true of all hobbies, but especially with music: it’s so much fun in the beginning because you’re learning a lot and progress comes easy, and there’s so much to experience and so many decisions to make, and: so much to buy.

There’s a school of thought that you should just stick to the basics when you’re starting out, and I think that’s probably true if you are trying to become a professional. But the whole point of a hobby/second creative pursuit is that it’s not the main thing—you can explore and create without worrying about the final output. There’s no pressure to publish/perform.

If you limit yourself too much, you only deny yourselves those pleasures. Trying a bunch of things is also a good way to figure out what aspects of the hobby you’re most interested in, which often leads to you sticking with your hobby for longer and, hopefully, really settling into it.

Of course, it’s easy to get carried away (see: music gear subreddits) and spend money you shouldn’t spend and acquire stuff you don’t have room for and don’t end up using.

One limit I put on myself is that if I’m going to purchase a piece of hardware (I currently own three small hardware synths, an audio interface, a couple of midi controllers, and a drum synth), it has to be something that gives me unique sounds or music sequencing capabilities that I can’t easily arrive at using software synths. I’ve stuck to that so far.

LESSON TWO: The basics are important, but it’s okay to extend beyond them when you’re starting out so long as you don’t go overboard with your spending.

However, at some point you need to move beyond exploration into mastery. Or rather: if you’re interested in the joys of your hobby that come with mastery, then you’ll need to become more methodical about that. You will exhaust your natural ability and the easy gains and end up plateauing. Some folks just stay there. And that’s totally valid. But I strongly believe there are pleasures to be found in pushing beyond that.

For me, the easiest way to channel myself back into the basics was to learn modular synthesis.

All electronic sounds that aren’t recorded from acoustic instruments (and even those can be manipulated once you record them), require synthesis. That starts with something that generates a sound wave and then involves various ways of manipulating that sound wave.

With synthesis, you start with a voltage controlled oscillator (VCO) to create the sound wave (the basic shapes are sine, square, and triangle); an ADSR (attack, decay, sustain, release) envelope that shapes the behavior of the sound wave when triggered (so for example, a very short attack, a bit of decay and pretty much no sustain and release leads to a percussive or pluck sound—you would need to increase all four to get an organ sound); and a voltage controlled amplifier (VCA), which governs how loud the sound is.

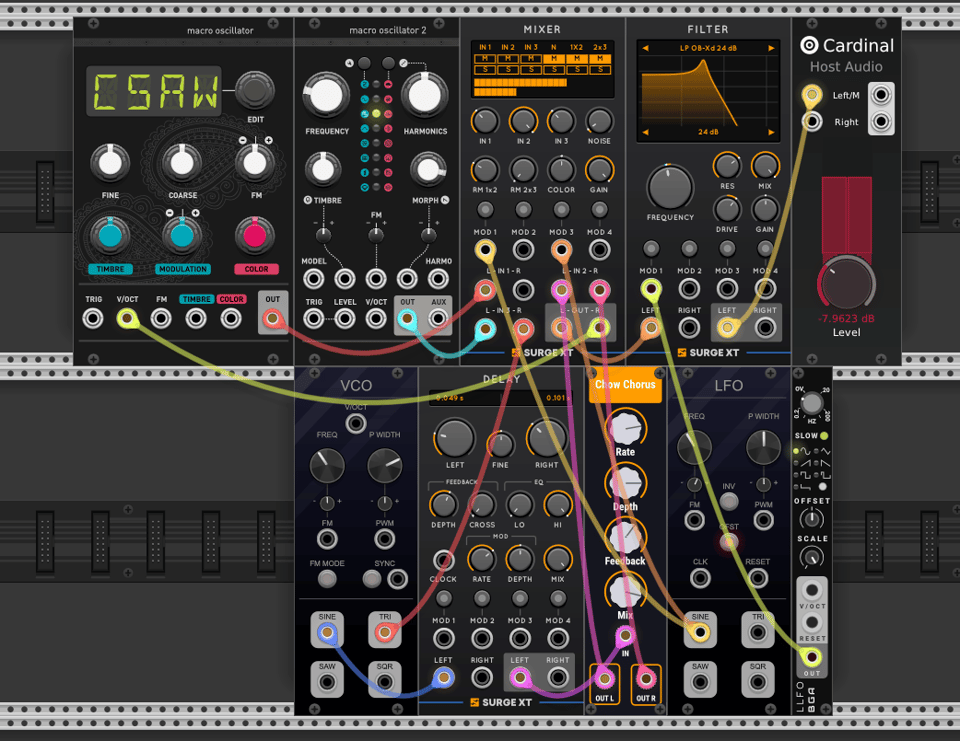

Here's an example of what that looks like:

Note the use of the word voltage—all electronic music is, essentially, the manipulation of the flow of electricity. There are a lot of things you can then add to this basic set up to change the nature of the sound. But it all starts there.

The beauty of virtual modular systems is that every single component—the VCO, the ADSR, the VCA, etc.—is a separate module you add to the instrument you build. And what you add, how many, and how you connect them together—how you direct the flow of voltage—and the other modules you use beyond the basics is all up to you.

Note also that I’m using the word virtual. There are hardware systems where every module is a separate piece you buy (with most modules costing $100-500) and you put them all in a special case/rack and connect them and rearrange them and buy more because you also need a module so you can get your audio out or because you want to add drum sounds or would like to add some reverb. But hardware rigs are expensive. A set up that will do just the basics could easily be $1,000, and you need to get up into the $2-3k plus range to do something really interesting.

With virtual modular you can do a lot with free or low-cost software/apps. And that has allowed me to get back to the basics. I’ve made some lovely sounds with my software and hardware synths. But even those that allow for powerful sound shaping techniques come pre-packaged and pre-routed. This is what gives them their unique character. But that can also impede base-level understanding.

LESSON THREE: When you plateau, go back to the basics and do so in a systematic, affordable way.

Presets, templates, instructions, patterns are all helpful when starting out—and beyond. And that’s all some folks want, which is fine.

But at some point, your skills get good enough that you may want a blank page so you can more easily experiment.

To a certain extent, that’s what happens when you open a project in digital audio workstation (a DAW like GarageBand or Ableton Live—I’ll write about DAWs in the future), but even there, you can quickly load a synth plugin with a load of presets to choose from or a drum kit with a bunch of kick and snare samples. With virtual modular, you truly start from scratch. And that can lead you down some paths you wouldn’t normally go down. Which is hard, but also a lot of fun.

LESSON FOUR: A blank page, canvas, screen, workspace is scary, but it’s also liberating. Embrace it.

So that’s some of what I learned from using virtual modular synthesis. I’ve created more than a hundred patches (individual instruments) using it. Most of them suck. But some are kind of cool, and for all that the music I make mostly comes from synth plugins and hardware synths, making a place for virtual modular has really helped me grow as a musician (which sounds weird to me—but music producer also sounds weird).

I hope these lessons translate to whatever creative hobbies you pursue or would like to pursue.

Here’s a photo of the virtual modular instrument I used to record one of the drone parts for A Basin of Ink.

RECOMMENDATIONS

FICTION: Sunyi Dean’s The Book Eaters didn’t exactly go under the radar when it was published in 2022, but even if you’ve heard of it, you may not be aware of how weird and emotionally impactful it is. It also is doing something interesting with noir as genre in (urban?) fantasy. It’s also a vampire novel even though, they’re not “classic” vampires. I’ll let the marketing copy explain: “Out on the Yorkshire Moors lives a secret line of people for whom books are food, and who retain all of a book’s content after eating it.” If you’ve read it (or end up reading it), I’d love to hear what you think about it. This is one of those novels that isn’t going to work for every reader, but will really strike a chord with certain readers.

NON-FICTION: I recently re-read The Weird and the Eerie by Mark Fisher. It has its’ flaws (and blindspots), but it’s worth engaging with simply to stay in touch with how strange modern life is and what that means for literature.

MUSIC: I continue to be interested in where experimental, electronic, ambient, and classical music meet. A recent find that scratched that itch is Sarah Davachi’s “Selected Works II.” It’s on the ambient side of things, but the tonalities are more classical/experimental than the kind of ambient that gets too cinematic or New Agey and so I find myself more interested in the listening experience of it.

For something different, try the goth post-punk/post-rock band Midas Fall. “Cold Waves Divide Us” is their most recent release.

[NOTE: both links are to Bandcamp, which I recommend using, but both albums are also available on streaming platforms.]

FILM/TV: you all are probably already aware of the main things I’ve been watching recently that I’d recommend—Dune, Part Two; Slow Horses; Top Chef: S21—but some of you may not have heard of the anime Spy x Family (available on Hulu). It’s about a spy, an assassin, and a young girl with superpowers who is an orphan who end up as a family but aren’t aware of each other’s hidden lives. It’s delightful (and quite violent and sometimes cringeworthy at times).

That’s it for now! You’ll hear from me again in June.