Role models & poison

The trouble with marketing yourself as a "parenting influencer," some baby book recommendations for deaf kids, and preventing the destruction of deaf educatoin in America.

Hi, and welcome to the newsletter. If somebody sent this to you (and you like it,) you can subscribe here. Also, my agent tells me I need to bulk up my social media, so you can follow me on Bluesky, Instagram and Facebook.

Perfection, California: pop. 0

Look at my beautiful family, drenched in the honey-color sun that spills down on us, in the fragrant rose garden of the gracious Berkeley cottage where we live. Notice the true bond between my children, their unconditional love for each other, and the perfect love and care which my wife and I shower down upon them. See our happiness and our perfection; gaze upon the basilisk.

Writing nonfiction—let alone selling it—is mostly making choices about what’s useful to share, and what’s TMI. The truth is that on Sunday, I let my children watch 5 hours of television. Saturday, I was distant and distracted with Leo when I took him to the zoo, our only one-on-one time for the week. Friday, I was grouchy with Oscar when I drove him to school, and I yelled at him about his shoes. My ASL skills keep deteriorating. I drink 6 cups of coffee a day. I’m at least 15 lbs overweight, and my skincare routine could use some work.

“I’m not a role model” is a line you usually get from pop singers and disgraced actors in the middle of their reputational comeuppance, but it applies to dadfluencer wannabes like me, too. Perfect parenting is impossible, and utterly unnecessary for the well-being of your kids. But if you read most parenting books—if you read my book—that idea gets a lot less traction than it should.

There’s structural reasons for this; a book that focused too much on my personal shortcomings would be tedious and unsellable. Focusing on a reader’s shortcomings is a much better strategy, especially if you want to start a cult, but you don’t do that by insulting the reader; you work by comparison, offering an unattainable ideal to for them to chase. Social media has has run with that tactic by selectively presenting highly curated images of Australian surfer mommies, with all the natalism and none of the stretch marks. It’s true that beauty = engagement, but it’s depressing, and can make even our best efforts seem like a failure in comparison.

And for parents with deaf kids, perfectionism is a hides a greater threat. As author Laura Maudlin lays out in her book, Made to Hear, Listening and Spoken Language approaches to oralism explicitly appeal to the hyperparenting impulse. Eyes open, ears on. Never miss an opportunity. Your child is at risk. You must be eternally vigilant—therapy happens 24/7, and the parents are the therapist. Or anyway, that’s what real parents do. The pressure is even more insidious because oral tactics have uneven outcomes, so they’re like pumping quarters into a slot machine hoping for a payout—unpredictable results are the most reinforcing and addictive. So for parents whose best efforts aren’t enough, the first response is often more oralism.

But perfectionism hurts bilingual families, too. Starting a new language and learning a new culture in midlife, let alone under the conditions of parenthood, just isn’t going to be a smooth ride—you need a special kind of patience and a tolerance for failure. ASL-hostile professionals know this, and will prey on parent’s insecurities, but pro-ASL folks don’t always take the time to temper parent’s expectations, or give them a sense of what “good enough” really means in this context. Dads are at particular risk, but self-doubt and self-sabotage knows no gender.

All of this doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try, every day, to be the best parent possible, but the word possible is key. I hope my book shows other parents the possibilities. I hope it doesn’t show them the basilisk.

Save the Deptartment of Education

While I’ve got you here, and if you’re an American, take a minute to to call or write your congressperson and your senators, and tell them that you don’t want president-elect Trump to dismantle the Department of Education, as he has promised to do.

Our children rely on the DOE for school funding and the enforcement of IDEA and Title II rights that are the basis of deaf education in America. Deaf author Sara Nović is helping head up the charge, and you can learn more at her Instagram, or go directly to her Substack page for instructions on contacting your representatives and heading this plan off before it even gets to congress.

We’re all burned out on politics, but if you care about deaf children, you can’t skip this one.

Beyond Brown Bear, part 3

As the proposal for the Deaf Baby Instruction Manual makes the rounds, it’s come time to get its online identity in order. I put a lot of practical recommendations in it about books, videos, legal documents, etc., always with the line, “find out more at willfertman.com.” But I suddenly became afraid that potential publishers might actually check to see if these links were actually there, so instead of working on the newsletter the past couple weeks, I put together a resource page for parents.

I wanted to keep it straightforward, helpful, and uncontroversial; little did I suspect that one of my recommended authors wrote one of the most-banned children’s books of the 2020s.

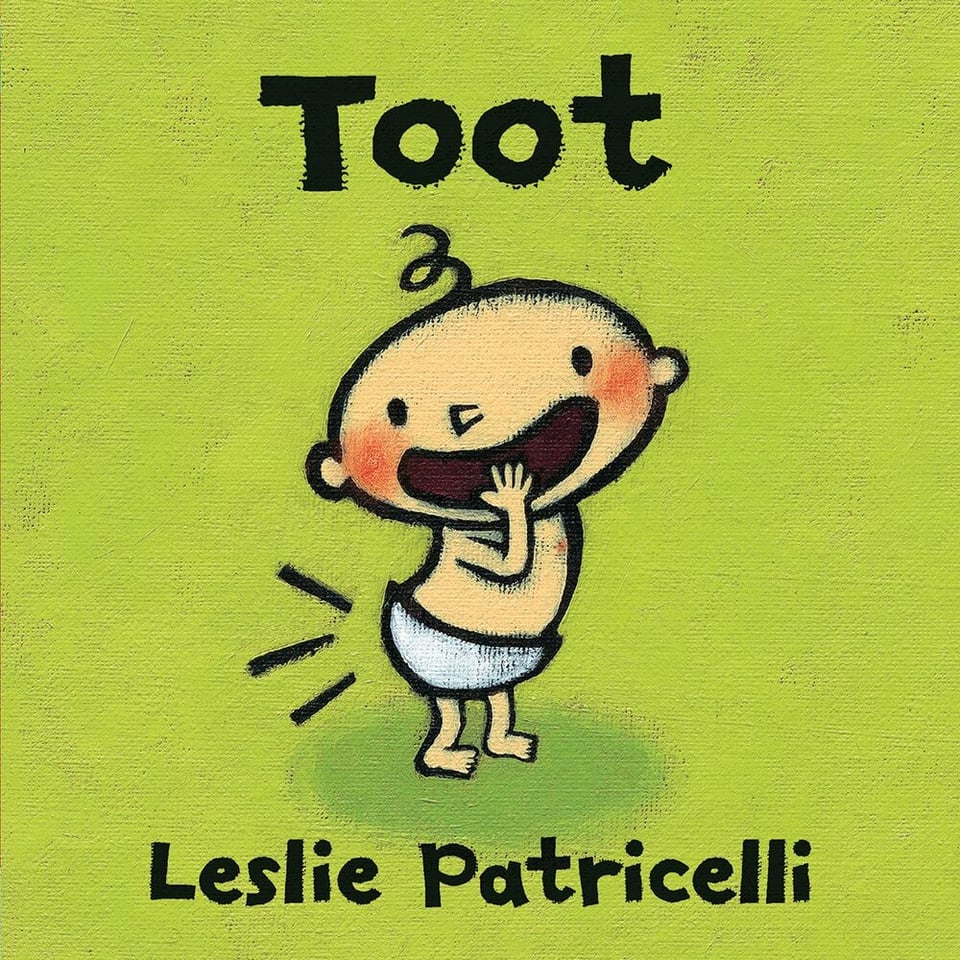

I put some ASL-centric works on the list like the Handtalk series and the Love and Language books, but just as many simple-to-sign board books that parents might already have on hand, like the Leslie Patricelli’s baby books.

You only need two or three signs to make it through her simplest stories, like Baby Happy, Baby Sad or Yummy, Yucky—the bright, funny illustrations will carry you the rest of the way. As your skill grows, you can tackle more, describing her signature baby, their situation and their feelings in greater detail, so the books hold their value from infancy through toddlerhood.

Her slightly more complex books like Mommy or Splash are great for advanced beginners, with straightforward, declarative sentences and dialog told from the nameless baby's point of view. These often rhyme, but unlike many rhyming kid's books, they don't rely on the rhymes to "work," so they interpret well into ASL.

Patricelli's books also often focus on a child's body and their functions—Hair, Tooth, Toot, Potty, etc. Young children are utterly captivated by these topics, and the stories are a useful visual aid to start introducing ideas about potty training, self-care, pride and bodily autonomy, giving hearing some extra help while they build up their language skills.

The current resource page is just the beginning. I know I’ve left a lot out—people tell me Monster Hands is the new hotness—so please take a look, and let me know what I’ve missed.