Good answers

New research puts a stake through the heart of Count Oracula, the "learning ASL hurts English literacy" vampire.

Research Alert

The meat of this newsletter is a very exciting piece of research coming out of the UK about the benefits of sign language for deaf kids. However, I put a self-satisfied preamble in front of it, so if you want to get to the Tootsie Roll enter of the Tootsie Pop, skip to ‘Looking at the Big Picture’ in the bottom half of the email.

If you got this email from a friend, and you like it, please subscribe to my newsletter.

And my agent still says you should follow me on Facebook, Instagram and Bluesky. Bluesky especially; it’s the most fun.

Inquiring minds

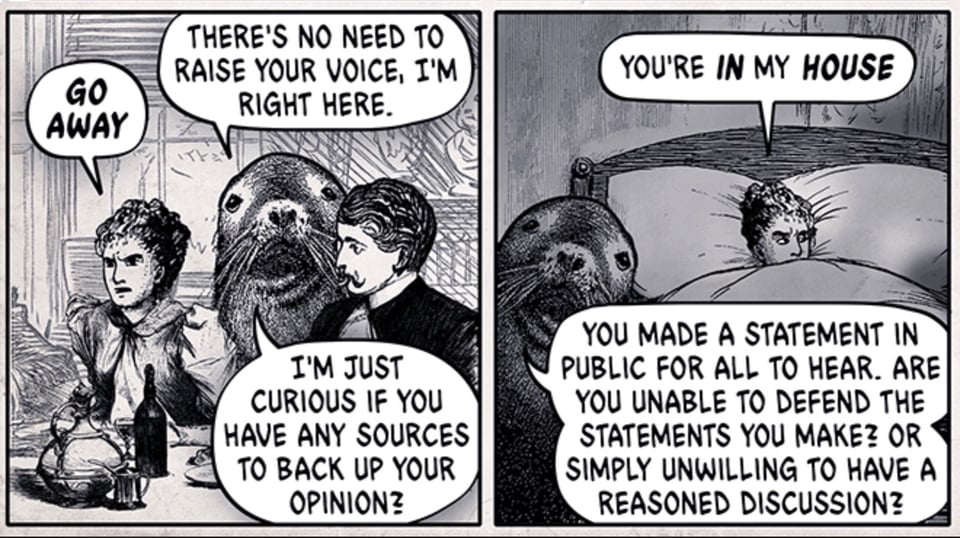

Anyone who says “there are no bad questions,” obviously hasn’t been paying attention. Skim social media for a minute and you’ll discover that not only is asking bad questions possible, questions can be bad in many ways.

Online discourse has nurtured and a whole ecology of dishonest questioning, from sealioning to JAQing off, but bad questions have been with us long before the Internet. There’s one in particular, though, posed in various ways by oral proponents, that’s hung over deaf education for more than a century like a hot fart in a cold car: “Does ASL help deaf kids learn English?”

This is a question of the “bad in their faith” variety, because it wasn’t something that the 19th century eugencist-oralists who posed it were trying to answer.1 The question they were actually getting at was: “How do we stop Deaf people from making babies with each other?”

To answer this second question, AG Bell and his contemporaries needed to generate a toxic cloud of doubt over “manualist” education as a whole. So they posed that first, bad question as a part of this larger campaign to break up Deaf social networks by suppressing the generational transmission of ASL.

But as often happens, time went on and the question’s original purpose was forgotten. Folks lost track of the fact that this was just some bullshit designed to generate doubt in parents and legislators, leaving subsequent generations to contend with the “unproven” value of sign language instruction for deaf kids.

The stink runs deep. In the six or so years I’ve been paying attention, I haven’t seen a single research paper supporting natural signed languages not get poo-poo’d for one failing or another. The funny part is that neither I nor the hard core oral proponents over on Facebook that I argue with—let alone policymakers and politicians—actually have the background to truly critique current research. It’s all vibes-based, and the Volta Bureau set the vibes a century ago.

Because of this, bilingual education is still struggling in the US. Although we’re living in a time when the evidence that sign benefits deaf children is stronger than ever, no single paper, no matter how clear or how compelling, really cut through the funk.

Looking at the big picture

So I’m sending big love to researchers Dr. Dongbo Zhang, Dr. Hannah Angiln-Jaffe, and Dr. Junhui Yang, who decided to use a sledgehammer when a flyswatter just wasn’t working. The authors, writing in the journal of the British Educational Research Association, looked at 52 separate studies of sign language from the past 40 years, and performed a meta-analysis—a way of making mathematically grounded, apples-to-apples comparisons between different bodies of research.

They identified sets of skills children use in sign languages—things like knowledge of vocabulary, proper sign production, understanding grammar, etc.—and cross-checked with skills kids use in spoken/written languages. This produced a mighty mountain of data in service of answering a very good question: “Do abilities in sign languages for deaf children support abilities spoken/written languages?”

Their analysis is highly technical, but the short answer is yes. Every sign language skill had a positive correlation with every spoken/written language skill.

I asked Drs. Zhang, Anglin-Jaffe and Yang to summarize some highlights, emphasis mine:

We found that a wide range of abilities in sign language are closely linked to d/Deaf students’ spoken/written language abilities, showing that skills in sign language can “transfer” to support literacy learning. For instance, the link between sign language comprehension and reading comprehension was notable, as was a very strong relationship between fingerspelling and reading comprehension in elementary school children.

Another surprising result is that knowledge of sign language grammar supports skill in spoken/written language grammar. Deaf children are known to sometimes mis-apply sign language rules when using spoken languages, but their active thinking about how languages “work,” including differences in rules between languages, is beneficial, and ultimately helped them make meaningful sentences.

The results are really exciting, and will be the basis for much more interesting work in the future. But while the details are important for developing better deaf educational pedagogy, I worry that the complexity of the analysis—70 studies from 52 papers from 14 countries of 14 signed languages and 8 spoken languages over 42 years with 202 documented correlations—is going to obscure the essential story.

Because of entrenched beliefs among professionals and policymakers, this particular paper faces the same uphill battle as the studies it draws from, not to mention that the political climate in the US is tipping against evidence-based policy of all kinds. But there’s never a wrong time to clear the air, and I think Dr. Zhang et al set immaculate vibes that I hope will carry us into the next century:

Nurturing sign language in deaf children is important. Children and families certainly don’t have to be “sophisticated” sign language users for them to enjoy that benefit. For education, as our findings showed, even the most basic sign skills, such as fingerspelling, transfer to support literacy learning.

Although our study has education as a focus, the importance of sign language for deaf children goes far beyond that, as numerous other studies have shown. Nurturing sign bilingualism is no easy job. Parents are the best, and the most immediate, support for their deaf child. So, why not start a journey of learning sign language together with your child?

That’s a good answer.

1. I know that this is a bit of a strawman—if you read Bell’s Memorior Upon the Formation of A Deaf Variety of the Human Race, you’ll find that while he asks all kinds of interesting questions about heredity, he just asserts that sign language is bad. He doesn’t even bother begging the question.

Minda the scientist adds, “Rather than yes or no, scientific questions are more often answered with ‘it depends’ and ‘to this extent’

“We don’t just ask, does penicillin cure pneumonia? We ask, when and how often does penicillin cure pneumonia? The answer is:

when the pneumonia is isn’t an antibiotic resistant variety

when the patient isn’t otherwise immunocompromised

when it’s not caused by a virus

then penicillin cures pneumonia 90% of the time. ‘Yes or no’ doesn’t cover it.”

She also shared that she was trying to create a relatable example by using bacteria and antibiotics, and that she is very pro-science and pro-medicine, so please take all doctor-prescribed medications as directed. :)