Changing Your Professional Mind: an interview with Kim Ofori-Sanzo

Dr. Kimberly Ofori-Sanzo is a hearing speech-language pathologist, and the founder and director of Language First, an organization that “aims to educate and raise awareness about American Sign Language / English bilingualism and the importance of a strong first language foundation for Deaf and hard of hearing children.” She’s also a co-founder and board member of the American Board of DHH Specialists, a certifying organization for professionals working in Deaf education, rehabilitation and research, which launched this year.

I was excited to speak with Dr. Ofori-Sanzo because she’s been advocating for deaf children for almost exactly as long as my son has been alive. When Oscar was born in 2018, Language First was one of the only professional organizations1 honestly discussing the impact of language deprivation syndrome, and how ASL could prevent it. Importantly, they also talked about language deprivation’s social context: how doctors, therapists and educators were causing iatrogenic harm by insisting on English-only interventions for deaf and hard of hearing kids and steering parents away from natural signed languages like ASL.

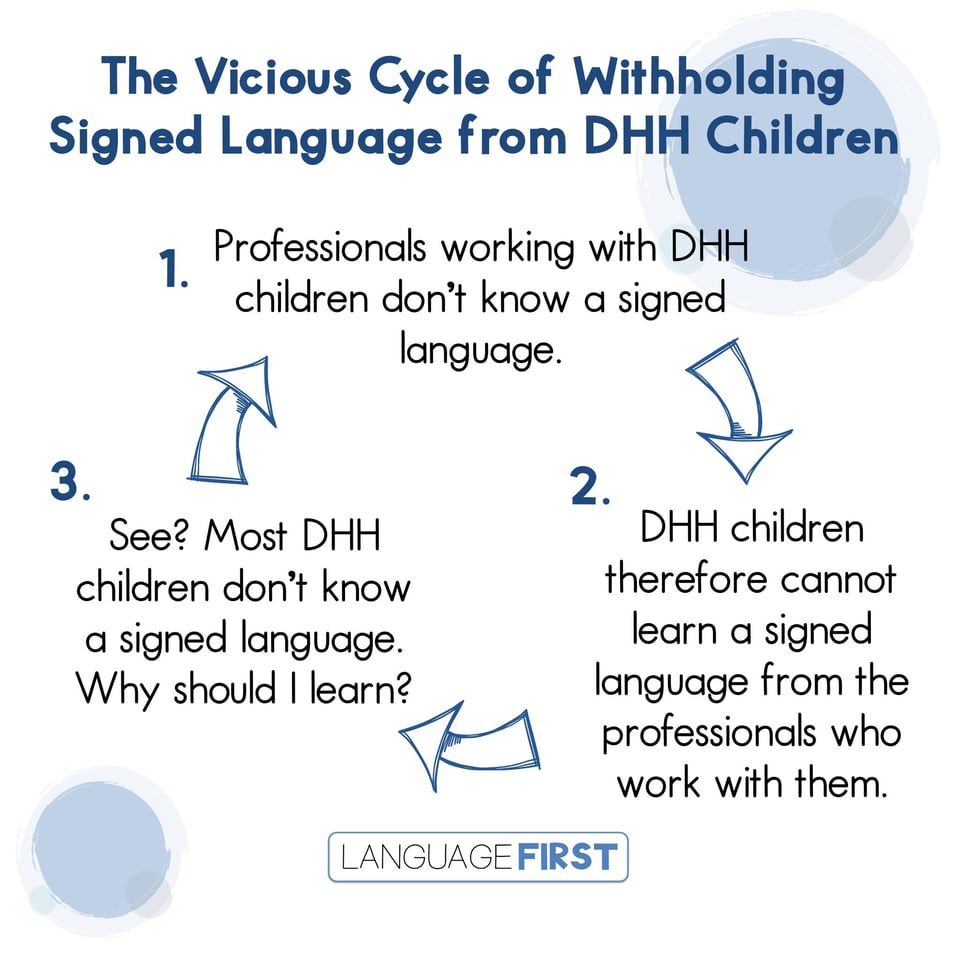

Finding Language First online was a revelation—their position was a brave and radical break with larger professional organizations like ASHA and EHDI, which at best were equivocating about signed languages, and at worst actively suppressing ASL education and research2. Beyond that, Kim was a true poster, who knew how to use social media to its greatest effect. Language First’s pithy memes and growing online network led me to professionals who helped support my son’s education, and to the people and the science that shaped much of my thinking for The Deaf Baby Instrution Manual.

I spoke with Dr. Ofori-Sanzo by phone in late August of 2024 about her experience as an SLP, as an advocate for deaf kids, her new project, and the difficulties and rewards of changing her mind. The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Will Fertman: How did you get interested in speech-language pathology and ASL?

Dr. Ofori-Sanzo: It began when I was getting my degree in Communication Sciences and Disorders—that's the undergrad major for speech-language pathology and audiology—and I started taking ASL. At the time I genuinely didn't know what I would use it for, because I thought that all deaf kids just signed and didn't learn to talk. I was so naive.

Then I went to Gallaudet for my master's degree, which was also in speech-language pathology, and that’s when I realized, oh, okay, I would get to work with this population, but maybe in a different way than I initially thought. I ended up at the American School for the Deaf (ASD) in Connecticut, and that was where I spent the majority of my career.

“Professionals are [giving] misinformation that causes even the most well-meaning or the most well-educated parents to make poor decisions for their kid.”

Even in the first couple years at ASD, I remember thinking that something's not adding up. It didn’t make sense that all deaf kids would struggle with language; there's nothing inherent about being deaf that makes you struggle, but I couldn't put my finger on it. And then I found Dr. Sanjay Gulati's presentation on language deprivation syndrome and thought "Oh my God, this is it. This is what's happening. It has a name and people need to know about this."

My mind was blown, and I was freaking out.

Were there any events or clients that were turning point in your career?

There was a seven year-old who had come to us with bilateral cochlear implants, but literally no language. It was painful just to see the severity of his language deprivation; he didn't know his own name. But his parents were super-involved. They were trying everything, and very well-educated.

I thought, "How is it possible that the parents want to do everything right, and they seem to have the education to get these concepts, but he still has no language?"

So when I started working with him, I did voice-off ASL; I did not work on English at all. There was no point, right? And when I talked to his parents about this, they said, "We were told not to sign with him."

That case really opened my eyes to the fact that it's a medical-professional issue. Professionals are not educating parents properly, or giving them misinformation. That causes even the most well-meaning or the most well-educated parents to make poor decisions for their kid, because they're like, "Oh, you're a doctor." They trust that you would know.

How did your clients respond to your change in practice?

Oh my God—seeing them improve with that kind of therapy is the one thing that I miss about the job.

I'll never forget this one girl who had a similar story. She also comes to me at the age of seven, with two hearing aids, and again has literally no language when I started working with her. Her teacher also was very fluent in ASL, so she was lucky to have good ASL models everywhere that knew what they were doing.

“I started being very vocal—probably obnoxiously vocal—about what was happening.”

By the end of the year, she went from no language, to holding conversations with us. And she was also producing oral words, because once she had ASL, she was able to make connections, just exploding in her language. I loved seeing that.

Her parents were saying, "Wait, how did that happen?"

It was because we gave her the language foundation first.

I saw so many cases, especially when they came on the younger side: 5, 6, 7 years old. You can see this huge improvement when they're explicitly taught language through their most accessible modality. That was awesome.

When you began changing your practice, did you have mentors or peers you could talk to about it?

I feel like I was lucky. The other SLPs I worked with were also Gallaudet graduates, very fluent in ASL, so I went into work and just said, "You guys, look what I found!"

I became known as the person who spoke out very, very loudly about language deprivation, even on committees at school. I had already started asking "Why am I covering my mouth? Why am I doing this?" Eventually I stopped doing auditory therapy altogether, especially if my kids were older and they were not making progress. I didn't understand why we were doing it when our kids just needed language.I started being very vocal—probably obnoxiously vocal—about what was happening.

Eventually, I changed my practice even more; I started going truly voice-off, working on linguistic structures in ASL. Before, I was always doing a little SimCom, working on both languages simultaneously, and after I started really learning about language deprivation, I thought "Nope. They need true biz ASL, and intensive therapy in how this language is structured."

© 2024 Language First

Language First has a big online footprint—I first became aware of your work through Facebook. How did that start?

I had a social media account that I used for posting about work, and I decided that I would totally refocus my social media to only talk about language deprivation, because how is this not a thing that we're trained in?

That was 2019. At the time, language deprivation really wasn't something that people discussed. So that was how we got started; I just continued to post on social media, reading research articles and posting quotes from them, all while working at ASD.

By 2022, it got to the point where it grew so big I couldn't continue my full-time job anymore, so I left ASD to do Language First full-time.

When you started putting your views out online, what was the reaction from other professionals?

The initial reaction to Language First was extremely negative. For the first two years, I struggled, thinking, "Why am I doing this? I need to quit. This is impossible."

People were so mad that I was saying these things. I got a fair amount of positive messages, but I got a lot of really mean, really nasty, sometimes threatening messages.

“You strike this nerve, ‘Oh, damn. Have I been harming deaf kids? No. No, I haven't.’”

Threatening?

Yes, about me and my family—my husband, who has nothing to do with deaf education. This is why you'll always see me cover my daughter's face in pictures online. It freaked me out because other professionals were so threatened by the fact that I'm calling out this crisis. It's their livelihood and they feel very attached to it, and how dare this person say that they’re hurting deaf kids? So yeah, the first couple of years were rough.

You know Rachel Zemach? I would Zoom with her and cry and say "I can't do this." And she told me, "You have to keep going. Please. You have to keep going because you're the only SLP I've ever seen that actually says stuff like this."

Now, I pretty much never get negative messages. I don't know if people just got used to our presence and figure they can’t stop me, or if people have slowly started to accept what we’re saying. But it's become a little more normalized—the things I'm saying are not as out in left field as maybe they were in 2019.

What was your read on their reaction? What was the emotional subtext of all this?

You know when you are accusing someone of something that they did that was wrong, but they're saying that they didn't do it, they don't want to admit it, they get defensive, right?

It felt like a part of them knew. A lot of people make their whole career their identity—I mean, I have, too. Their identity is that they help deaf kids to listen and talk, and they're very proud of that. All of a sudden someone is saying that what they’re doing might be hurtful.

You strike this nerve, "Oh, damn. Have I been harming deaf kids? No. No, I haven't," and you get really defensive because how dare this person insinuate that you're hurting kids?

People don't want to sit with that feeling, especially because it’s not intentional. A lot of practitioners are not doing it intentionally, they genuinely think they're helping. The vibe I got was, "I need to scream at you to get it out. It makes me feel better to just attack you than to look inward."

People are in it to help; suggesting they aren’t helping is very threatening.

Exactly, and that's why I try to tell people that just because you didn't know any better doesn't make you a bad person. You were genuine: that's how you were taught, that's how you were trained. You did what you did with the information you had at the time, and the information was that you shouldn't sign with these kids.

But there's something to be said for being able admit, "Now that I know that I should sign, okay, I'm going to transition to that. What I did in the past can't be undone. I did it with the information I had, what I thought was right, and now I know that it's not right so I'm going to shift."

Have you ever had colleagues who have these really negative reactions but then come around to your viewpoint?

Yeah, actually. There was one woman that I worked with who was an SLP-AuD [dual speech language pathologist and audiologist.] When I first started getting really vocal at ASD, she got pretty defensive and would kind of snap in meetings, and make little comments, "Well, bilingualism doesn't work for everyone."

“I don't see how my videos impact people. I just post them and hope for the best.”

How would you react to those sorts of comments?

I either wouldn't react, or I would just say something really neutral. "Yeah, yeah, you might be right," because she's a colleague, she's in my department. It got to the point where she was so mad about my advocacy, and that I was getting asked to do all these different things, that she went to the department head.

Eventually, we had a heart-to-heart. I said, "Listen, I don't care that you work on listening. We need someone to do that. That's fine. I'm just saying that for me, that's not my cup of tea. You can continue to and work on kids' listening skills. But why does it bother you that I want to work on bilingualism with ASL as a foundation?"

By the time I left, she was much softer and would say things, "You know, I think a lot of kids do benefit from signing,"

And I'm like, "Yep. Good job."

I think I wore her down to a certain extent.

You must hear from other professionals now who are changing their practice. How do they talk about their experience of correcting course?

Oh, yeah. I've had a few people who will message me on Instagram.

They'll say, "You know, I used to SimCom a lot, and then I noticed my ASL was crap when I SimCom. I took your advice and I followed some of your tips, and the other day I noticed my student improved so much because my ASL was so much better, so thank you for that." That kind of thing, you know?

So those are cool messages to get because I don't see how my videos impact people. I just post them and hope for the best, so it's kind of cool to be like, "Oh, you follow my advice? That's awesome.”

If you were going to tell a fellow professional to change their approach, what's the first piece of advice you'd give them?

Well, if they already know how to sign, I would say first and foremost, stop SimComming. Separate your languages. Use ASL as the foundation. Use your ASL to teach them language, and then once they get these concepts through this visual language, then you can make parallels spoken English or written English.

If they're not fluent in ASL, that's a little trickier. Then I would recommend, first, go take some ASL classes, but is there a Deaf colleague who can help with this child? Maybe you need to think about putting them in another setting where they have Deaf people around them.

“‘You're going to limit the number of SLPs who can get accredited,’ —I mean, that's literally the point!”

I want you to talk just a little bit about the American Board of DHH Specialists because it’s very exciting to me. First, can you tell me what it is?

I'll give you the backstory: speech-language pathologists have a large scope of practice, so the American Speech and Hearing Association (ASHA,) has “board specialties” that allow you to get certified in specific areas. You can be a board-certified stuttering specialist, or board-certified for dysphagia [swallowing disorders.] Specialties have a really high standard of knowledge for a very small part of the field.

There are only four certifications right now, so back in 2018, ASHA opened up the process, and you could apply to create new certifications. Another signing SLP and I applied to make one for DHH kids. Right? How awesome!

It's a three-year, three-step process, months and months of work. You have to write up your rationale, why the certification is beneficial, who needs it, etc. We started in 2020, and they approved us at step one and two. And then, at the third step, in 2023, they denied us over a reason that was related to step one!

We think that they did it because we were requiring a high level of ASL proficiency. They even said, "Well, you're going to limit the number of SLPs who can get accredited," I mean, that's literally the point!

But in their rejection letter, they also wrote that, "We encourage you to pursue this certification independently," and we thought, "Okay."

The positive of doing this independently was that we could now get Deaf and hard of hearing people on the board. We couldn't really do that through ASHA; there's barely any DHH SLPs in the world, and when we asked them if we could invite outside board members, and they said that they had to be ASHA-certified. But for ABDHHS, we can have a rule that 50% of our leadership must be Deaf or hard of hearing, and we can open it up to more than just SLPs; we can open it up to any professional that works with deaf children.

I feel like that rejection actually allowed us to bloom into this really cool organization with a variety of options for people to get certifications:

One is a practice track, so if you currently work with deaf and hard of hearing kids in any capacity or birth to three, school age, whatever, you can apply for the practice certification.

One is an academic track, so if you're scholar—someone like Wyatte Hall, who's made his whole career in Deaf-related studies, you could also apply for the academic certification.

And then we made a third associates track where we partnered with the College of New Jersey and created a deaf language associate program. They worked with Matt Hall, and it's a degree for Deaf people to learn how to do language therapy in ASL and get a degree out of it.

“I want to do the best that I can to help deaf kids, but not at the expense of other Deaf people.”

Why would a professional want this certification?

There are two big motivating factors. One is that the Listening and Spoken Language certification—the LSL AVT cert—is something parents seek out. It signals to them that clinicians have achieved some high level of skill.

We need the equivalent of that for ASL-English bilingual practitioners because parents currently cannot just look at someone's credentials and identify these professionals. How does a parent know that they have a high level of proficiency in ASL and in treating dhh kids? Right now they have to do their own research.

Then the other part was that parents deserve to be able to find people in their area who know what the eff they're doing.

(That's exactly what happened to us. We were looking for an ASL-fluent SLP for a long time, and I think our experience was atypical only in that we actually eventually found somebody after a full year of searching.)

Now you're working in two organizations that benefit deaf children. How do you deal with the fact that you are a hearing person who's leading the charge in many cases? I know you've come in for criticism from members of the Deaf community—how have you changed your work in response, and what's that kind of balance like?

I think I've learned a lot. When I first started, I didn't understand how my hearing privilege even played a part; I genuinely didn't get it. And after years of conversations with Deaf people and learning more, I've come to the realization that I want to do the best that I can to help deaf kids, but not at the expense of other Deaf people. Now, I always make sure that Deaf people are involved in the work that I'm doing: our Language First team is at least 50% Deaf, including the board.

So A) is always trying to make sure that deaf people are involved, and B) is just being humble—being able to admit that as a hearing person there are things that I don't know and that I will never understand, and being able to say "That's not a job for me," or, "That's not a place for me," or "That's not a situation where I should be leading."

“How do I know if I’m good enough? How do I know what I'm doing is even right?”

It's sticky because I know it can come off as having a little bit of a savior complex. It’s more that I see these things that need to be changed, and I know that I have the privilege, but also the network and the manpower to be able to change it. But I always ask, how can we make sure that Deaf people are involved, and that things that maybe aren't appropriate for me, I won't do?

For instance, if there's videos that need be signed in ASL, I'm not going to sign them—I'll pay a Deaf person to do it; I refuse to let a Deaf person do anything for me without pay. It's little things like that. There are still people who just truly believe that I shouldn't be doing it, period. But I think most people feel that, as long as Deaf people are involved in the creation of these different things and have their say, that helps.

I mean, I'm a hearing person writing a freaking book about raising deaf children. I’m waiting for the (very appropriate) Deaf pushback.

But you know what? We had Christina Pacala, a hearing mom of a deaf kid, and she did a webinar for us about how she uses ASL English bilingualism with her child. Because again, parents are like, “Where do I start? What does it look like in day-to-day life?"

And we had someone email us and ask, "Why do you think it's appropriate for a hearing parent? Why do you think she's an expert?"

And I responded, "She actually is an expert on being the hearing parent of a deaf kid." You know what I mean? You can't take that away from people. Yes, she's not Deaf, but the fact is that 90% of deaf kids have hearing parents, so they want to know what other hearing parents have done. Yes, of course, we also look to see what Deaf parents are doing, but you can't deny that there's a unique experience of a hearing parent who had to learn a brand new language. In that specific thing, yes, she is an expert.

You recently had a child yourself; how did that change your view on all this?

It gave me a new appreciation for how freaking hard it is to do the things I'm asking parents to do.

I already know ASL, and I’m trying to sign with my baby who's not deaf. If my baby actually was deaf, and I wasn't fluent, trying to give them language when I’m sleep-deprived and hormonal and crying every day and unable to function… It's hard to just survive with an infant, never mind also learn a language and try to give it to your child. You have this feeling: "How do I know if I’m good enough? How do I know what I'm doing is even right?" It's a critical period, and you’re losing moments every day.

We’re asking a lot from parents, and I’ve started to think about ways I can make it easier, or at least coming off as less demanding, because it is incredibly overwhelming. I think it is each person's unique experiences lead them to a particular place, but everyone should be able to talk about issues and learn more.

[1] Of course, Deaf activists and groups had been advocating for ASL and warning about language deprivation for years before it even had a name.

[2] See ASHA’s ongoing opposition to LEAD-K legislation as one example.