A happy marriage, oversight, and representation

Fighting back against Trump's attack on Deaf education and one of the best Deaf kid's books I've ever seen.

In times of crisis, we all turn to loved ones; I turn to my smart

'n sassy wife. She’s deeply invested in the well-being and success of children—ours and everyone’s. So here’s what she had to say about Trump’s attacks against public education, what it means for our deaf kids, and how we can take action.

It’s okay to panic.

In fact, we probably should.

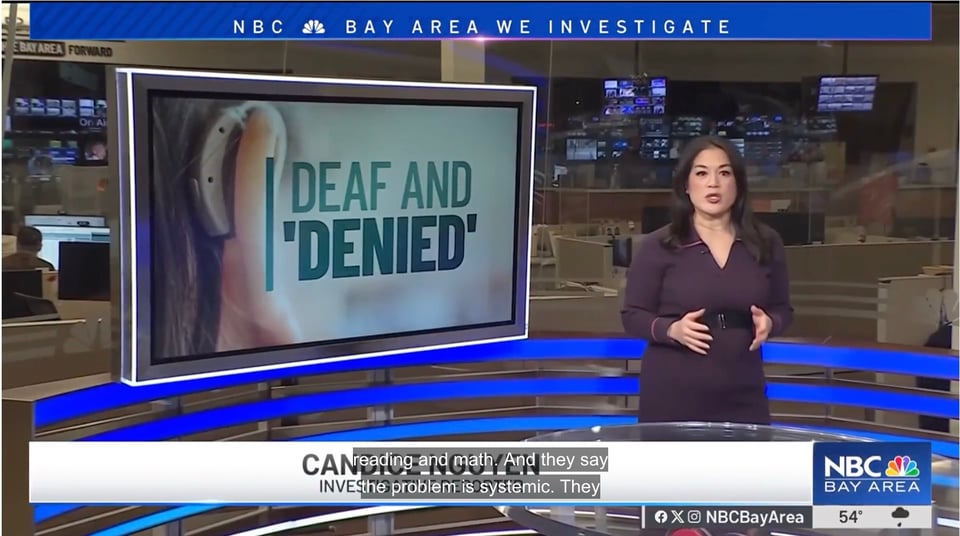

Here in California, the Santa Clara County Office of Education is in trouble. Santa Clara schools were supposed to be educating Rodi Flores, a mainstreamed deaf student, to the same state standards as every other child in their district. Instead of teaching him, though, they kept passing him, grade after grade, eventually graduating him without basic math and reading skills. Yep, they gave him a high school diploma, even though he reads only at an elementary level.

Worse yet, the special education program is accused of conning Flores’ mother into signing an IEP that disqualified him from post-high school education, leaving him both uneducated and unemployable. And now, three more deaf students have come out, sharing a similar story.

“I signed the IEP thinking they knew what was good for him.” Flores’ mom was quoted as saying.

Sound familiar?

For many parents of deaf children, this is going to ring a bell. The message coming from professionals, SPED teachers and school districts is the same as always: don’t worry, we’ve got this covered, look the other way. Trust us.

But why should we? What evidence do we have that local school districts have the interest of deaf children in mind?

This is coming up on a national scale right now with the multi-state lawsuit against 504 and the dismantling of the Department of Education. In online parent groups, I keep seeing parents saying to one another, “it's okay, this won’t harm your child.” And worse, I see educators saying the same thing: “Don’t worry, we’ve got it covered.”

But let’s be real—why wouldn’t it harm your disabled child?

And help me out here—why should I not be worried?

Parents who argue in support of the dismantling of 504 and the Department of Education claim that it will return education to the states, “where it belongs.” But that’s not really true. Education already belongs to the states—what doesn’t belong to them is oversight and funding, and that’s what is being stripped away. So once the money and the eyeballs are gone, the states can choose to follow the law…or not. If they can afford it.

After all, we already know what happens when a state is left to its own devices.

In Michigan, deaf student Miguel Luna Perez attended public school for twelve years, and the school straight-up lied to his parents about the progress he was making. Although he entered school already in need of basic language support, he was assigned a paraprofessional who did not know ASL, and who left him for hours on his own. Meanwhile the school gave him inflated grades, leading his parents to think that he was on track to earn his high school diploma—however right before graduation they told his family that he only would receive a “certificate of completion”, because like… he went to school every day for twelve years and came away with with nothing but some home signs and severe language deprivation.

This ended up being an expensive lesson for the school district. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, who found in Perez’s favor. In short, he could sue the school district for monetary damages in a ruling enforced by… oh wait, a Federal body!

Were it not for the oversight provided by the feds, we would never have even known about this.

People talk about panicking like it is a bad thing. But why? Panic is what made me a top student in my ASL class after my Deaf son was born. Tell me that panic never led you to apply for that stretch-job, study extra hard for that test, or motivated you to finally get checked to make sure that cough was just a cough. (P.S., I hope it was just a cough!) Panic is good. And friends, this chilled out, middle-aged, overweight yoga mom is telling you: IT IS TIME TO PANIC.

So what can you do, my panicked friend?

Get the email of every parent you know who’s worried about this stuff. Will said this in his last newsletter, but it’s important. Once you have those emails, share information about local and national issues. Then, if you need to contact a lawmaker, or show up at a protest, you have allies.

I keep running into parents who feel isolated and helpless, but your best backup are the other moms and dads in line at dropoff. Politicians know that if three people are in their office, there are thirty people out in the community worried about an issue. And if there are ten… well… Tiny groups can have a huge impact.

Join organizations fighting back. Some of the biggest opponents of the Trump administration are nerdy and unfamous groups made up of lawyers, educators and bureaucrats. Just this week, a series of major legal victories have been won against some of the administration’s worst actions.

Besides ACLU, NAD and DREDF, look to Disability Rights Watch, as well as National Parent’s Union and Protectpubliced.org, which has been picketing in Washington DC outside DOE offices. Nerds rule, and they need your support.

Share your story with the public. Protectpubliced.org is collecting parent stories to share with the media. There is not enough mainstream coverage of the impact that the destruction of the DOE or Section 504 will have on families. These stories are key to building political power, and we still need to get the word out.

Share your story with your Congressional representatives, in writing or via a phone call. The administration is pretending like Congress doesn’t matter, but it does, especially if you live in a red or purple state. You can find your members here: https://www.congress.gov/members/find-your-member

Remember that you are the parent. When we were kids, who did we turn to when we were full of anxiety, or afraid of the dark? That’s right—mom and dad. Superheroes and protectors. Now you are mom and dad, and your kids need you. You are present, you are paying attention, and you have the tools to make a difference.

So, do it.

Beyond Brown Bear Part 5: Monster Hands

So far, I’ve mostly reviewed books I’ve had the pleasure of personally signing to my kid. This next one was published last year, though, and as I’ve said, Oscar reads on his own these days. So my usual “can I sign it?” analysis is going to be brief: yeah, probably?

It’s a challenging book from the perspective of a hapless hearing dad, with the kind of tightly-looped English that requires a level of conceptual translation and classifier skills to put across in ASL:

“Shine your light on the wall,” signed Mel, “and make monster hands. Use them to ROAR. Monsters do not like it when shadows ROAR!”

Co-authors Jonaz McMillan (Deaf) and Karen Kane (hearing) do a joint reading of the book here, so you can see for yourself.

But the more interesting part of Monster Hands to me is the way the book represents ASL and its ASL-using characters.

The story is simple. Milo read a scary book before bed, and he’s freaked out. He signals his best friend Mel across the street, and she coaches him through his fears, scaring the monsters back with some shadow puppets of their own.

The two protagonist children sign to one another1 and their ASL is depicted in the illustrations2, but whether one or both kids is Deaf is left unsaid. It’s a different choice when compared with previous picture books like Moses goes to School or Boy (ugh,) where the story centers around a child’s Deaf identity.

It’s an interesting choice that sets the tone of the book: rather than a didactic story story about what Deaf kids do, it’s a story about being scared of the dark and letting a friend lend you some courage. ASL is involved in a gimmick, but the gimmick is making classifiers into shadow puppets. This is second-order play with the characteristics of ASL—less like a language lesson, more like a poetry lesson.

“Deaf but not mentioned” is something you see more often in books where kids have hearing devices and use English, like 2020’s Moonlight Zoo, where the protagonist’s hearing aids are visible but not remarked on. Those sorts of stories land in a very different context, though.

Zoo is a story about a child looking for their lost cat inside a gorgeous dream, moving through different habitats in the titular zoo. Nothing strictly requires the text to discuss the protagonist’s deafness, although it’s interesting that the final resolution hinges on the girl hearing her cat’s meow. But the story also exists in a real-life world where children and parents can be pressured to minimize their deafness and downplay their difference. So while the book undoubtedly reflects the experience of many oral deaf and hard of hearing kids, it can also result in a kind of erasure.

In contrast, Monster Hands doesn’t take any time teaching you about the Deaf character’s identities, and the D-word does not appear in the text. It’s just possible to imagine a very sleepy hearing parent reading this story to a hearing child and totally missing the fact that the characters are using ASL with one another. But that matter-of-fact, I’m-not-going-to-draw-you-a-diagram depiction feels pretty good to me. It’s not coincidental that before Milo reads his scary book, he also reads “a book about a snowy day.”

Representation is a deep well, and I’m not well qualified to take its full measure, but I’m glad McMillan and Kane took the route they did.

Beyond this, the book is notable for other interesting unremarked choices: neither protagonist is white. The boy is initially the fearful one, the girl is the brave one. The kids support one another and solve their own problems—no adults appear in the story at all.

Support one another, solve our own problems…

1. From opposite sides of the street! The whole story happens as conversation between their bedroom windows, a neat bit of Deaf Gain.

2. Not all their signing, just key words. Illustrator Dion MBD captures the characters mid-sentence, focusing on the emotions and reactions of the two main characters rather than making diagrams. The point isn’t to teach you ASL, the point is to show two kids communicating.