They Want Self-Hate, But They Can't Get It

Book bans aim to create a cycle of self-hate and shame in creators. It won't work for me.

“My strategy of separating myself into parts and pieces—pieces I cared about, pieces I ignored—repeated what I saw done to women around me, whether in real life or in the media. It was normal to see women and their bodies criticized and dissected, objectified and consumed. No matter how successful they were, they were too fat, too crazy, too much. And if they did maintain a perfect physique, then their talent came under attack. Their career was a joke, their latest single a failure, their art seen as meaningless, trite. These impossible, unhealthy, contradictory standards set in the world around you? They climb inside you and breed.”

I wrote those words in an essay called “Our Whole Radical Anatomy,” which published earlier this year in the multi-starred anthology Banned Together: Our Fight for Readers’ Rights edited by Ashley Hope Perez. My invitation to take part in the collection came because my book Body Talk: 37 Voices Explore Our Radical Anatomy has been slowly added to more and more lists of books deemed “inappropriate” for teen readers.

This week, Body Talk landed on yet another list. This time, it’s the list of nearly 600 titles that Department of Defense Education Activity (DODEA) schools–our US military schools spread across the globe–must remove. It’s a helluva list that makes zero excuses of its targets. The books are nearly all by or about LGBTQ+ people; people of color and race/racism; and puberty and human development. To use the parlance of those who’ve been banning books nationwide for the last four+ years, they’re books about “gender ideology” (formerly ”comprehensive sexuality [sic] education”); “DEI” (formerly “critical race theory”); and “social emotional learning” (a term that seems to have fallen out of favor but that encapsulates basically anything not captured by the previous two, including books about disability or books which help foster empathy skills).

These books are targets not because of fear. They’re targets because of hatred, and that hatred is not solely about the book banners projecting their feelings. It’s also about teaching creators to direct that hate internally. Developing a self-hate and shame cycle is a powerfully effective tool for silence.

Body Talk was first banned in February 2022. This was a little under a year into the noticeable rise in book censorship. It was banned in Collier Schools in Tennessee, where administration in the district ranked library books based on how queer they were and made decisions about the books’ futures on those slapdash, inconsistent standards. “Lucky” for me and for Body Talk, it was only a tier one ranking. Some side characters were queer and as such, the book was returned to shelves.

The ranking was factually incorrect. Both myself as editor and several of my contributors are queer. But we were not, I guess, queer enough to “earn” a higher ranking; those making these determinations got it wrong while simultaneously erasing the realities of our lived experiences. A piece of myself and pieces of so many of my fantastic, brave contributors were discarded.

I don’t talk about being queer a lot, and the primary reason is that it doesn’t take up a lot of real estate in my life as an adult. I don’t want laurels or space given to me for being queer when there are queer folks much more engaged in the community who deserve that. When there are queer folks whose lives are targeted and endangered in ways mine is not because on the outside, I look straight as an arrow.

But appearances are, of course, only that. It’s a lesson thread intimately, deeply, and passionately within Body Talk.

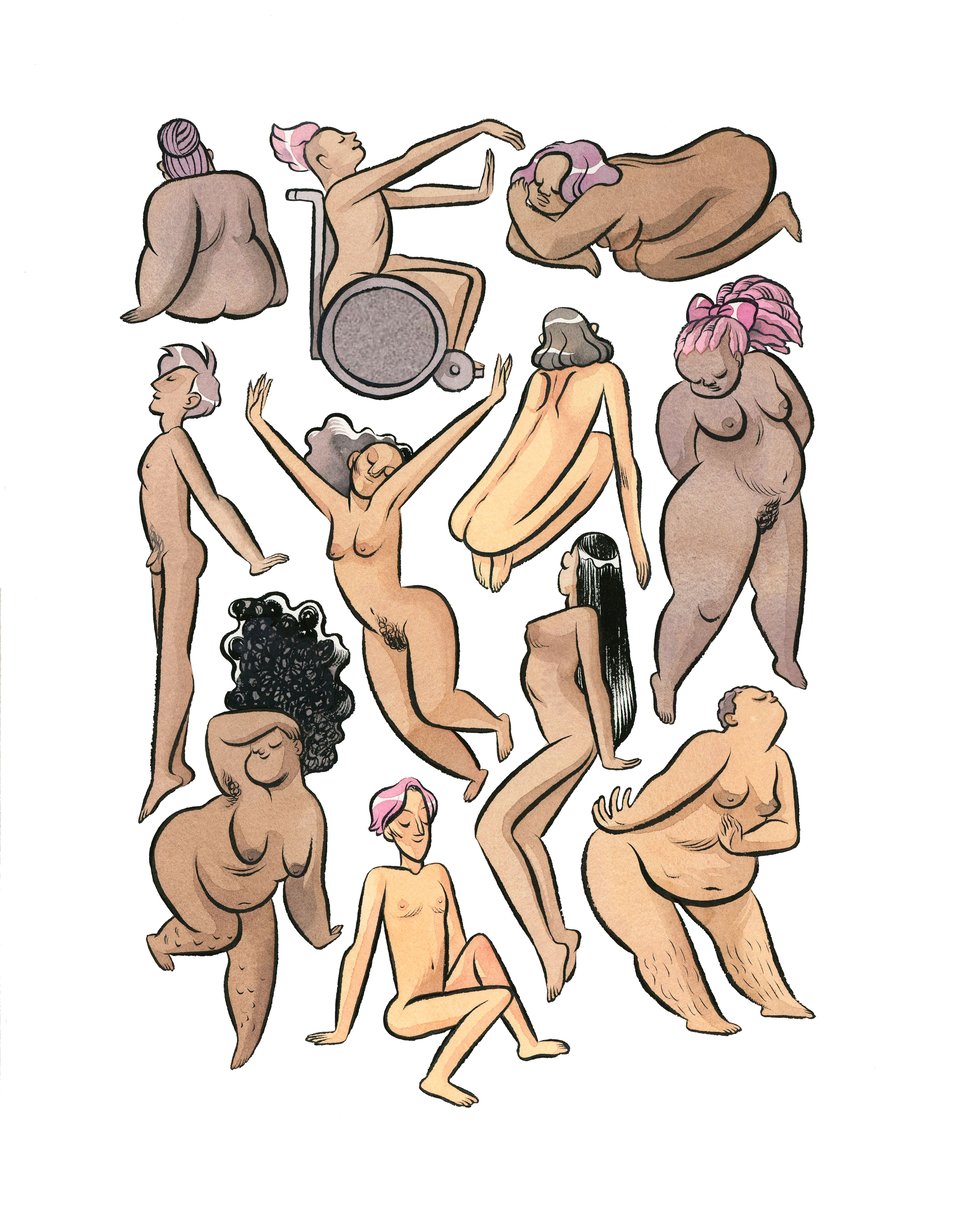

The second time Body Talk was banned came in September 2022. It was pulled from Wentzville School District in Missouri as part of state law SB 775, which bans “any depiction or description of sexually explicit material, which include sexual intercourse, genitalia, or “sadomasochistic abuse.” The law leaves room for materials with serious artistic or scientific merit, but apparently some comic-style images of queer bodies do not rise to that criteria (and the bodies in those images are unabashedly, joyfully queer!).

In Body Talk, Benjamin Pu talks about how he learned he had testicular cancer and urges those with testicles to pay attention to what’s happening with them. Shane Burcaw humorously addresses the realities of being disabled and having a sex life–something beyond imagination for far too many people and something buoying for disabled people who wonder if a happy, fulfilling sexual life is possible.

There’s more, I guess, that meets the law’s demands in Body Talk. Doctor and author I.W. Gregorio talked about penises, since her piece was about things that people with penises should know about, well, their penis. Gavin Grimm talks about his work ensuring that people of any gender have access to bathrooms which make them most comfortable. Madame Gandhi talking about menstruating while running a marathon. You’d know her by the photo that went viral from the 2015 London Marathon.

It might not be possible to pinpoint exactly which essay or piece of art crossed the ever-moving and made-up legal line, but it is not impossible to see the book pulled apart piece by piece. Adults spending their time sexualizing books for young people is, by any rational mind, uncomfortably weird, too. Adults erasing the reality that some bodies bleed and some have testicles and some rendered sexless in the imagination do, in fact, enjoy pleasure is not normal. It is born of internal hate.

In 2023, a school board member in Wilton-Lyndeborough Cooperative Middle/High School (New Hampshire) sought to get my book banned. She and her partner in complaint pointed to Shane’s essay, as well as Dr. Gregorio’s. By her estimation, the book had no value at all for any reader.

Body Talk was the first book banned in the state, though thanks to significant pushback from the community, it was returned to shelves. This last part is something that most authors never actually get to hear. I only did because I spoke in New Hampshire earlier this year, and a community member from that district told me how hard people fought. That was an event highlight for me.

It was a reminder, too, of how important the work being done on the ground by champions motivated by love of story, love of information, and love of people truly is.

November 2023, ban number four. This time, it was Bruce Friedman in Clay County, Florida. He was angry that I wrote about his project to ban thousands of books from the district. It was the first time my book was banned in retaliation for my anti-censorship work. Though the district reasoned that the book was illegal under Florida’s book banning laws, Bruce had made it clear enough in his vast spreadsheet of books to target that retaliation was why.

Bit by bit. Piece by piece. My body and the body of work I put together about the body, about the realities of having a body–good, bad, ugly–torn down.

January 2024, Body Talk was banned in Moore County Schools, North Carolina. This time there was no formal complaint. The book just disappeared and a year and a half later, there’s still no clarity around whether or not the book has been returned. Moore County Schools banned several other books for having LGBTQ+ representation at this time.

Bodies, silenced. Bodies, given no opportunity to even know the rationale for not being good enough. For being too much.

Then in September 2024, Oak Ridge Schools in Tennessee removed Body Talk because of state laws around their 2022 “Age Appropriate Materials” Act. The law wasn’t in effect until summer 2024, and I suspect this won’t be the only school in Tennessee tossing Body Talk out without bothering to read or review it. My book is reaching the point where if one school does it because of some law or other, the act is copycatted in other schools where they are simply complying.*

It’s likely there are dozens of other instances of Body Talk quietly disappearing or never appearing at all. Each is another cut.

The messaging here is not only inconsistent, it’s confusing. Either the book is so queer that it will indoctrinate young people into queerness–imagine if books had such power–or the book is not queer enough to qualify as dangerous to young readers.

Either the book is so explicit it qualifies as pornographic or it’s not. In some cases, it’s simply “inappropriate,” a tenuous term used when it’s clear material won’t actually rise to the standard of obscenity set forth by the Miller Test because it’s not at all obscene.

Each time I see Body Talk on a list, I’m reminded of how important the book is and how vital each of the voices within it are. I’m reminded of the time a teenager came up to me after a talk and told me that my book saved her life. I’m reminded of the time, just recently, another teen told me that my books were what helped her get through middle school and that she’ll always be grateful to the teacher who handed them to her. These are the people for whom my books are created. These are the people from whose hands my book is being stolen.**

I think of my 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 25 year old selves and how much hatred I directed internally because I was told that was what I should be doing. I was too much of everything and not enough of anything.

But then I think of my adult self rearranging the space in my mind, in my heart, and in my body where I allow such hate to occupy. No matter how many times this book is banned and no matter how hard people push to make me give up, to back down, to shut up, to shrink, to take up less space, the more necessary it becomes to do the opposite. To expand and to grow and to shout. To try new tactics, to deliver new messaging, to keep talking about my book and the tens of thousands of others being pulled out piece by piece. Being labeled wrong for some reason or other.

The more my book is teased into pieces, contradictory and confusing, the more crucial it becomes that my work comes from a place of unfathomable love. That love is for me first so that I can fill my own cup enough to then share that love as far and wide as possible.

I’m hurt, of course, to see my book hit the DODEA ban list. It’s an especially sharp sting during disability pride month. But I’ve been here before and I’ll be here again. Body Talk takes on more urgency as it’s divided into pieces by adults whose hobbies are lacking and whose ability to think critically or think for themselves simply don’t exist.

Body Talk isn’t just about the physical body. It’s about the political realities of having a body. It is a generous book about love, acceptance, and the ever-changing world in which we move our bodies. Book bans, both the ones enacted upon my body of work and on the bodies others’ work, are not about the books, nor have they ever been. They are about erasure and eradication. These aren’t about protecting children or teenagers. They’re about reinforcing a message that young people should hate themselves. Such messages make it easier to be subservient and dependent not only when they’re young, but as they grow into adults, too.

No matter how much the goal is to make me hate myself, I won’t. Only I control that mechanism, and I’ve found that love, empathy, and compassion are far greater fuel for getting through this life.

When you love yourself, the ability to love others is unparalleled.

“I won’t be sliced into silence. After all, I don’t write books so that lonely, bored adults can evaluate the ideas within these books through a lens of evil hatred, or disgust. I write for teenagers so that they don’t.” – from “Our Whole Radical Anatomy,” in Banned Together: Our Fight for Readers’ Rights edited by Ashley Hope Perez.

Notes:

*I’m suspicious that the DODEA list came from somewhere because it is a bizarre collection of titles. There are big names on there, the kinds of titles you’d expect on a “pull these books immediately” list from an uneducated and illiterate fascist regime. But then there’s my book, which hasn’t seen the level of banning that others on the list have; there are books on the DODEA list that have never appeared on a list at all. It feels so much like the 2021 Matt Kraus list in Texas.

**As of now, attempts to ban (Don’t) Call Me Crazy: 33 Voices Start the Conversation About Mental Health have been unsuccessful. I’ve yet to see an attempt to ban Here We Are: Feminism For The Real World. Both anthologies are also queer, colorful, and frank about topics like sex, race, gender, and ability. They just don’t call it out in the title as easily as Body Talk.