Book Bans Still Happen Loudly in States with Anti-Book Ban Laws

If book banning is being crafted to circumvent Freedom to Read bills, it's beyond time to call this a public health crisis.

At the end of 2024, New Jersey added itself to the growing roster of states enacting Freedom to Read/Anti-Book Ban bills.

At the beginning of 2026, two school districts in the state have found clever ways to circumvent the law and ban–or prepare to ban–books.

New Jersey’s Freedom to Read/Anti-Book Ban bill requires that local school boards develop and adapt policies on material selection and policies on where and how challenges to materials are evaluated. These policies are to be based on model policies developed by the state education commissioner, who worked in consultation with the state librarian, the New Jersey School Boards Association, and the New Jersey Association of School Librarians. New Jersey’s bill further disallows the removal of books by both school and library boards based on the origin, background, or views of the materials or their authors. Only people who have a “vested interest” in the school can put forward a challenge. The state’s bill also extends protections for library workers, exempting them from legal liability for protecting the materials in their collections.

New Jersey’s bill falls kind of in the middle of the pack of such bills that now exist in 13 states. Lawmakers gave several concessions from its original drafting to get it passed, including that the law doesn’t create obscenity protections for librarians and educators and that it doesn’t protect librarians from anti-discrimination laws when it comes to future employment (i.e., a book challenge in one district that a library worker defended can be held against them if they were to apply for a new job).

As these anti-book ban bills have rolled out nationwide, so, too, have the tactics to undermine them. In early 2025, Minnesota and Maryland lawmakers attempted to skirt their state bills by introducing legislation that would make it illegal for public schools to have books that contain “sexually explicit” or “sexually inappropriate” materials. The vagueness of the language is purposeful, since neither of those is a federally-regulated term in the way that “obscenity” is. We know such language is intended to permit banning of LGBTQ+ books, even if such books are exactly part of what’s being protected by these laws. A republican in Illinois is currently trying to undermine that state’s anti-ban bill, too, with a proposal that would require vendors to provide ratings on all of the material they supply to schools. Schools would then need to make those ratings available to parents. This bill won’t pass, and such vendor-rating requirements have already been deemed unconstitutional in a U.S. District Court in Texas.

Legislative tactics to circumvent the law aren’t the only methods being deployed, though. So, too, are numerous on-the-ground efforts by those eager to revoke access to a wide array of books for young people. We’ve seen it happen in the 13 states with protective bills–see, for example, how the Millburn School District in Illinois simply tried to remove an entire reading program from the school (and failed). As with all censorship attempts, we don’t always know what’s actually happening because, for the most part, it’s simply not documented.

In New Jersey, though, we’ve now seen two different underhanded means by which book banners are removing titles in just a month.

Readington Township School District’s New “Sensitive Materials” Policy

Readington Township School District’s attempts hit first. In late November, the district’s school board began discussing what they needed to do, policy-wise, to comply with the state’s new freedom to read law. The board was running up to the early December deadline to create such a policy, and some board members took issue with using the template provided to them by the state. One of the far-right board members performed a passage from a book she deemed “sexually explicit,” and some of the discussion turned to how they should develop a policy that emulates other New Jersey school policies in barring “obscenity” in their library collections. No actual examples of such policies were given.

At Readington’s January meeting, the board introduced a new two-part policy. The policy would make school librarians de facto censors of the library. Librarians would be required to flag potentially “sensitive material,” which would then be sent to a building principal, the Supervisor of Humanities, and a librarian from another building for final approval. This policy came after the district’s superintendent met with district librarians about the policy noting that they could not acquire “sexually explicit” material–and after librarians pointed out that such a carveout with vague language flew directly in the face of the law’s purpose.

From the TAPInto coverage:

Responding to the objections, board president David Rizza defended the process.

“It's not the board looking at every book, it's the librarian noticing something that might be sensitive,” he said. “What this does is it actually gives a procedure to the librarian to possibly say, ‘you know what, maybe this is sensitive. Maybe I don't have to make the decision on my own. I'll bring it to my panel of my peers.’ And then it escalates.

“Is that the board in the first step?” he added “The board's the very last step after it's gone through a bunch of reviews.”

Readington’s policy now puts the onus on librarians to figure out what “sensitive material” even is. Because that’s an impossible task, it’ll encourage librarians to purchase fewer books that students may be interested in, simply because they don’t have the time, energy, or know-how to determine which books will trigger the book banners.

There is nothing in the policy, however, about what happens when librarians don’t accurately identify “sensitive materials.”

Such policy is intended to have a chilling effect and lead to quiet/soft censorship. While librarians may be protected from litigation if they defend a book in accordance with the law, that doesn’t mean their reputation is protected. Neither is their future job trajectory (see the concessions made to pass the bill).

Readington’s book censorship policy, which you can read beginning on page 13, passed this week. That passage did not go down without a fight, but partisan politics of the school board made the final decision fall in their favor. Reasonable board members, alongside public comments, defended librarians and the right to read, while pointing out the policy's utter hypocrisy and the challenges of implementing it.

“I’m not going to sugarcoat my last sentence, and I want you to fucking look at me in the face … To the MAGA members of this committee, someday you too will have a starring role in the history books, and you will be compared to the Nazis and the communist censors of the past. I will not be silent as my beloved America falls into the hands of fascist wannabes.”

So what now in Readington? That’s the question. Most of these Freedom to Read bills have little or no teeth, and lawmakers and enforcers didn’t act in advance. At this point, the district’s policy can be sent to the New Jersey Department of Education for a ruling on its legality, but that’s only if the lawmakers who drafted the bill refer it there.

“Sensitive materials” is vague-speak for “what we on the right don’t like.” It’s a not-so-sly way to bypass the part of the law that bans bans on materials based on their origin, background, or views, and/or those of their author. In Readington, it’s twice as painful because not only will students lose access to materials they have a constitutional and state-level law right to access. Librarians are also now required to become the banners. It won’t be long before librarians see the consequences of not bowing to the beliefs of the school board, rather than meeting the needs of the students they serve.

Columbia High School “Pauses” AP Lit Classroom Read

For more than 11 years, the Columbia High School Advanced Placement Literature class has read the award-winning novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz.+ But that’s no more–at least not this year. The Interim Supervisor of English Language Arts directed the AP teacher to choose an alternate title due to an administrative decision.

What could be the reason behind ending a reading assignment that’s been part of the curriculum for more than a decade?

The unsubstantiated idea that Diaz’s book would impact the mental health of students.

From an article by one of the students in the class:

When asked to comment, Superintendent of Schools Jason Bing sent a lengthy statement (see attached below), stating in part, “As educators, we have the dual responsibilities of presenting our students with a rich and challenging education, using a myriad of instructional texts, and as well to protect and support their well-being, including mental health. Unfortunately we are in a moment in our community where we are experiencing a rash of mental health struggles both locally and across the nation, incidents of self-harm, and two recent tragic deaths.”

Bing added, “Given that the novel contains significant themes related to violent death, self-harm, and depression, it was determined that temporarily removing the text was the most responsible and supportive choice for our students at this time.”

In a moment of history where students are watching in real time as Immigration and Customs Enforcement is forcefully and cruelly removing people from their homes, detaining them in concentration camps, flying them to countries they’ve never been, and killing people for the mere act of witnessing such brutality–not to mention that students themselves live the day-to-day reality of school shootings, among other violence they think about and watch from the minute they wake up until the moment they go to bed–the notion that a single novel is contributing to the mental health decline of students is absurd. That it’s a book about the immigrant experience and navigating mental health challenges? Such a decision is patently offensive.

Bing’s reasons for pulling the book addresses the loss of several Columbia High School students in the last month, as well as several other losses. But rather than consider that the book is a crucial text for students to safely process and understand their thoughts and feelings about a reality for today’s young people–increased suicidality–the book’s been pulled. That it’s available in the school library is not the same as it continuing to be used in a classroom by advanced placement students who are 16 or 17 years old.

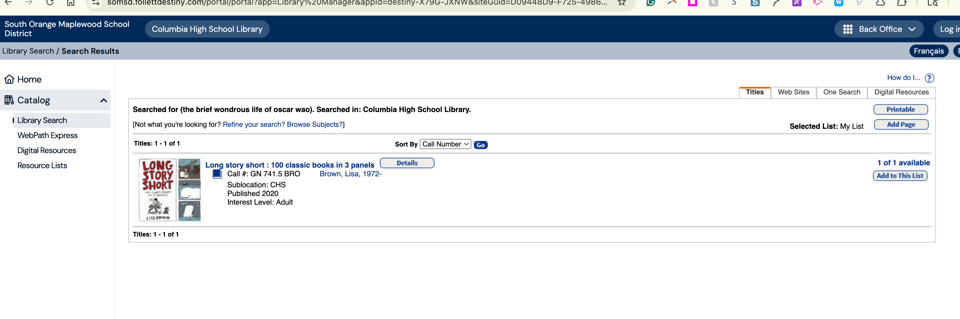

It should be noted that despite Bing’s claim the book is available in the school library, it’s not, actually.

Talking about suicide does not lead to suicide. It does not plant an idea or seed into the mind of the person thinking or talking about it. It’s the silence around suicide that leads to suicide. This is a hard fact for people to swallow because discussing suicide is taboo in our culture. But it is a fact–if we don’t talk about suicide, and if we don’t talk about it through safe means like art, then we continue to stigmatize the mental health situations that lead to people choosing suicide. A significant number of people think about suicide at some point; the vast majority of those same people do not act upon those thoughts. The gulf between thinking about suicide and acting upon it is massive. We have to talk about mental health, and we have to talk about suicide, or else we never provide the life rafts that those in that gulf need to come back to the safe side of the shore.

Bing’s comment about the need to be mindful of literary content in this moment is contradicted by the fact that other works of literature studied in Columbia High School–indeed, in the AP Lit class itself–include titles like Hamlet, which also discusses suicide. The difference, though, is that Hamlet isn’t about an immigrant, isn’t by a marginalized author, and doesn’t attempt to deconstruct toxic masculinity.

Certainly, this can’t be the first time that AP students have studied Diaz’s book while the district or school has had to grapple with teen mental health or a community-wide mental health crisis. It’s just a convenient time for one single book to become the load-bearer for a lack of mental health care and social-emotional learning that’s sorely needed for people trying to operate in America today.

The nearly 50 students whose curriculum was disrupted by a book ban have signed onto a petition asking for the book to be reinstated. So, too, have 135 other students who aren’t taking the class. The petition points out the fact that the district’s ban is out of compliance with the state’s law on book bans. Students are also planning to attend the next school board meeting on February 26 to explain the impact of this decision on them, their education, and their understanding and discussions of the mental health crisis affecting their community. Those in the community are invited to attend as well, and information about when and where the meeting happens is available here.

This is what the student petition says. It’s a masterclass in the kids’ understanding of what’s happening not only in their own lives but in the broader sociopolitical and cultural context, too:

To Administration of Columbia High School,

The AP Literature & Composition student body has been alerted that The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz has been pulled from the curriculum by English and Language Arts Department supervisor Ms. Suzanne Ackley. This decision comes at a moment when the integrity of education in the United States is actively being threatened. Under the current presidential administration, it is imperative that the censorship of literature not be perpetuated. English classes at Columbia High School have already read the book and attested to its message being one of utmost importance, one vital to our AP Lit curriculum and our understanding, as young people, to the realities of the post-colonial world. During a time of censorship on the national level, banning books sends a dangerous message about what we want being taught in our classrooms. By censoring literature, the South Orange and Maplewood School District is feeding into the current administration’s goal to block sustainable and meaningful education through censorship. The censorship of certain topics diminishes the ability of students to receive a comprehensive education; a complete education demands exposure to a variety of tough material and topics. As students in AP Lit, we believe engaging in difficult texts is not only appropriate, but necessary. The teacher of the class has furthermore agreed to provide an alternate novel if this one poses as an issue for certain students, and in class social worker support. AP Lit students have also expressed that they would be willing to sign a permission form in exchange to read the book.

In light of recent events at Columbia High School, it is more important than ever to sympathize and understand how mental health issues impact all people. By reading The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, the students of AP Lit will have the opportunity to be enlightened about the importance of mental health. Shielding these issues does not assist in empathy or understanding, but rather marginalizes them and renders them invisible. We are eager to approach this novel to understand the realities of mental health issues and their prevalence today which has helped students utilize the material for not only AP exam essay writing, but for personal exploration as well. Furthermore, the story’s discussion of immigration and acclimation to a new region remains important to empathize and understand why the current administration’s actions towards immigrants—especially those of Latin American origin—is foul and vile. By learning about the toll the immigration process takes mentally through Oscar Wao, a Dominican-American protagonist, students will further augment their empathy and knowledge regarding immigration and post-colonial affects.

As the student body of AP Lit we are concerned by the blatant censorship Columbia High School’s ELA department has chosen to take part in, and feel compelled to respond. Banning one book sets the precedent for more and more book bans that limit the integrity of our education. We want to understand and learn from difficult stories, even in the presence of tragic circumstances in our community.

What’s further distressing is that Columbia High School’s district–South Orange-Maplewood–has been cited as a model for effective policy and procedures related to New Jersey’s freedom to read bill. The district was a leader in declaring itself a progressive force in the right to read movement, passing a resolution on the right to read in September 2023, well before the state law took effect.

Not so much now, it seems. Leadership has not only bypassed the law but also undermined its own stance on inclusivity and the right to read.

If it’s happening in a district like this, it’s happening elsewhere. We just don’t know it yet. We know about in Columbia High School because the kids are standing up, demanding that their voices be heard and their rights be upheld.

While the student petition cited above is itself private, you can sign a petition here from Elissa Malespina that asks the district to reconsider this ban. Students would also be grateful for their story being shared far and wide; the story cited above was written by one of the impacted students. Because it’s not just them. There are thousands of others like them in New Jersey and beyond who aren’t able to get the word out far and wide.

American teenagers are dealing with a mental health crisis. So, too, are America’s adults. Unfortunately, those same adults who won’t address their mental health are turning instead to furthering a public and mental health crisis by restricting access to safe, meaningful ways to think and talk about the conditions and realities of our collectively worsening mental well-being.

Hours before this newsletter went live, word of a change in the superintendent’s plan hit the news. It’s now partially back on the reading list for students this spring, but with a carveout that parents can opt their students out of the assignment. Somehow, though, the latest update makes the situation worse, as it accuses the media of too quickly gravitating toward a “book ban” narrative–while also continuing to dig into the idea that a book can harm the mental health of its readers.

“For us, this is about the mental health of our children. Our district has been at the center of a conversation that conflates two entirely separate issues. We are seeing a ‘national script’ regarding book access being applied to a localized situation that is actually defined by a profound mental health crisis.”

These are not, in fact, separate issues. They are the same one.

So What Now?

Freedom to Read/Anti-Book Ban Bills aren’t a bad thing. But the vast majority of them don’t have teeth, making them easy to bypass.^ Just this week, Redlands Unified School District in California–where, yes, there’s an anti-book ban bill–has gone even further in trying to restrict what students in the district have access to. They’re not only banning books already on shelves. The board is taking steps to pre-emptively ban books and silence librarians into compliance, too.

From Redlands Daily Facts:

Under the proposal, as books are added to the library, they must be approved by the principal. A record would then have to be made detailing the title and author but it also must include who added the book and why.

The records would be kept in the principal’s office for at least four years.

The procedure would be standard and “ensure accountability and adherence to guiding concepts of decency,” a Feb. 10 report states.

Books in the library “should be reflective of diverse ideas and a balanced variety of perspectives, support the educational, emotional, and social development of students while also ensuring that materials are age-appropriate and wholesome.”

The proposed policy would prohibit books with perceived pornography, erotica, graphic descriptions or graphic depictions of sexual acts, sexual violence and sexually explicit content.

A few speakers spoke Tuesday in favor of the policy and said librarians need to be put on notice so there would be accountability.

Librarians “need to be put on notice,” and just the mere perception of ideas that the far-right deems inappropriate would be enough to ruin the careers and lives of library workers in the district. That’s not even to touch upon who gets to make decisions about what “wholesome” means as it applies to books in a school library.

That district passed its first round of cruel ban policies in August, and here we are in February, with more being added. Where has the state been? Where has any enforcement of the law been?

As of writing, the only state to have shown enforcement of its Freedom to Read law is Maryland. The state stepped in when a district attempted to ban books, and the state told them they violated the law. We need this kind of enforcement in every state with these bills; otherwise, they’re little more than symbolic.

Symbolism is important, and these bills serve as a reminder that some legislators are paying attention. That they’re allies to public and public school libraries and librarians.

But without enforcement, bad actors in these states will continue to find workarounds, stealing away from students and taxpayers their rights to access, study, discuss, and think about literature. In an era where we continue to panic-monger about how the kids can’t read and don’t read novels anymore, perhaps it’s time once again to think about why that is.

Perhaps it’s because the mere act of reading a book can’t be done without someone getting angry because said book might be by or about Brown, Black, Indigenous, or queer folks.

Perhaps it’s because young people are still not considered autonomous humans, too, but are instead seen as property to own and program.

As students in Columbia High School have shown, they do want to read books. They’ve just got grown-ups who think they’re not able to handle grappling with tough concepts, and thus, they should simply be shielded from those discussions forever.

Book censorship is a public health crisis.

+It would be remiss not to mention that Junot Diaz was among the numerous authors whose names were brought up in the 2018 #MeToo reckoning in publishing. Diaz took responsibility for some of the behaviors, and MIT cleared him of additional allegations.

^A Right to Read bill floating in Virginia right now has brought forth some great considerations from two different library professional organizations in the state, pointing out how by all means the bill sounds nice, but it’s got such big holes in it that it would likely be a boon to book banners more than freedom to read advocates.