Images From A Comic Panic Gripping the Nation

We know comics are and have been among the most censored books in America. According to the recent PEN America report, “Cover to Cover,” 73% of all graphic and illustrated titles feature LGBTQ+ characters or content, people or characters of color, and/or discuss race and racism. Though the contentious content has changed only a little bit since the emergence of the comic book as a format in the 1930s, what has sparked moral panic among “concerned citizens” has always simply been a reflection of the world as-is, rather than a fantasy of a world that isn’t.

The history of comics censorship is endlessly fascinating to me. Perhaps it has less to do with the format itself–obviously, the visual elements of a comic book are what make them such easy targets, as “concerned citizens” can simply open up a page and point to the thing that hurt them–and more to do with the fact that because we have a shorter timeline of the format’s existence. It is much easier to trace the history of the censorship with comics than it is with traditional books (though at least in America, we also know the origins of that tradition).

Comics came of age at the same time we had an explosion in popular media, and censors weren’t going to overlook the opportunity to stoke outrage in the magazines that middle class white women were purchasing at the grocery store checkout stand. That the federal government invested resources in exploring the damage comics caused to the (white, middle class) youth and those trials were broadcast onto televisions that were proliferating in the average white middle class households helped, too.

Let’s take a look at some of the media that published in the mainstream in the late 1940s through the late 1950s creating panic about comics. This was the era of Frederic Wertham and his book Seduction of the Innocent, as well as the era of the 1954 Senate Subcommittee Hearings on Juvenile Delinquency. These hearings were less about juvenile delinquency; they were about how comics were or were not leading to an increase in juvenile bad behavior . . . which, well, wasn’t actually happening either except maybe among young white boys. Something had to be the cause, right?

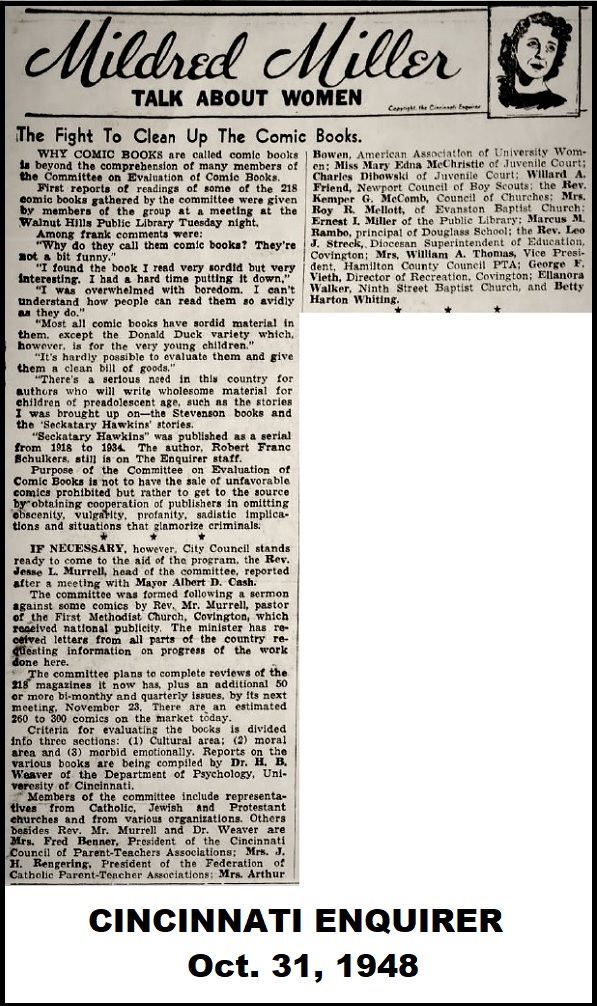

Now that World War II was over and the (white) middle class could begin to flourish, some women saw that they had an opportunity to be local heroes by “fighting” the naughty comics. This particular committee in the Cincinnati area was going to evaluate comics by “cultural area,” “moral area,” and “morbid emotionality.” Recall that the 1973 Miller Test or its 1957 predecessor, the Roth Test, had not yet been established. But lo, how much those three arenas of comic evaluation certain mirror the criteria used by the myriad groups taking up the mantle of authority now.

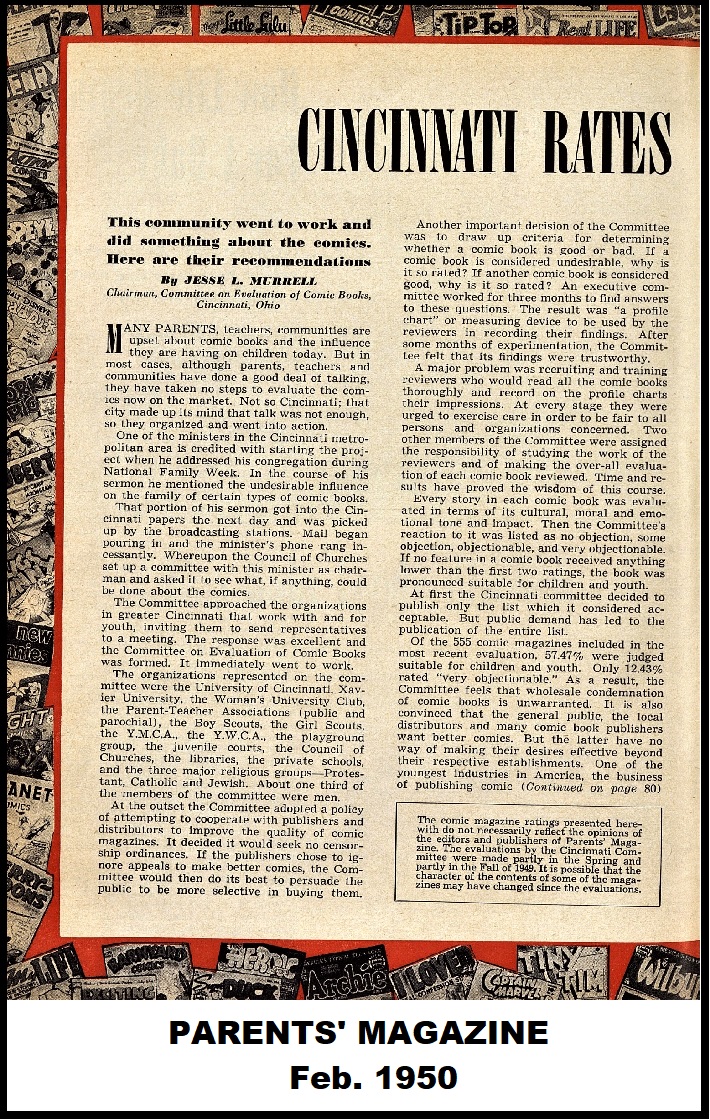

Curious about the outcomes of those reviews? Don’t worry–the Cincinnati Committee on the Evaluation of Comic Books got their word out and did so not just locally. They got their ratings of hundreds of comics published in Parents Magazine.

You will notice a nice disclaimer on the story, which is that the ratings presented didn’t necessarily reflect the opinions of Parents and that they may have changed in the period between their submission and publication in the magazine. How helpful!

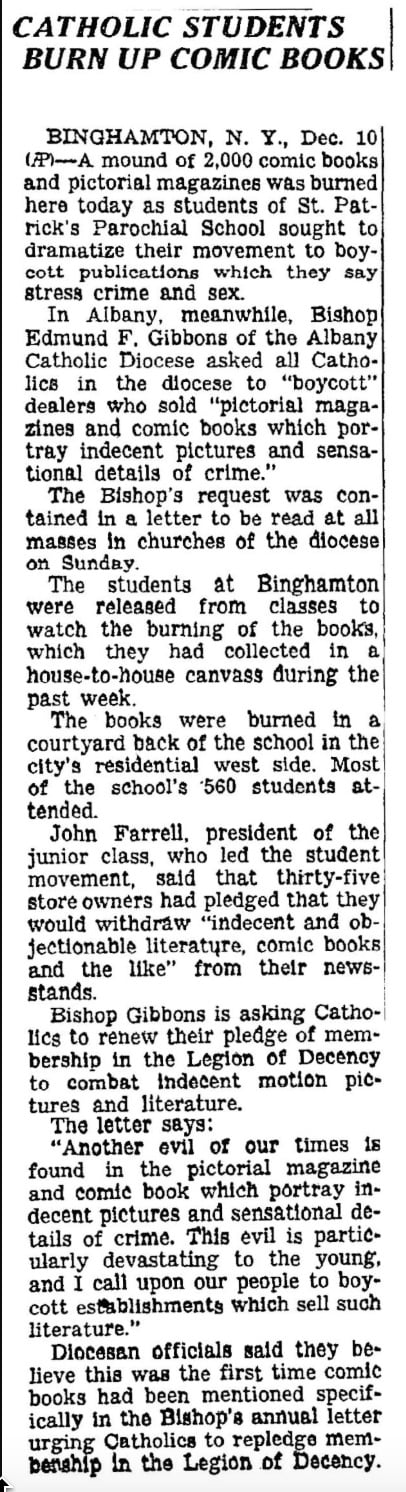

The above image is from a coordinated comics burning in 1948 in the Binghamton, New York area. It was most likely taken by Safford Lock,^ and below is the story of what was happening as published in the New York Times.

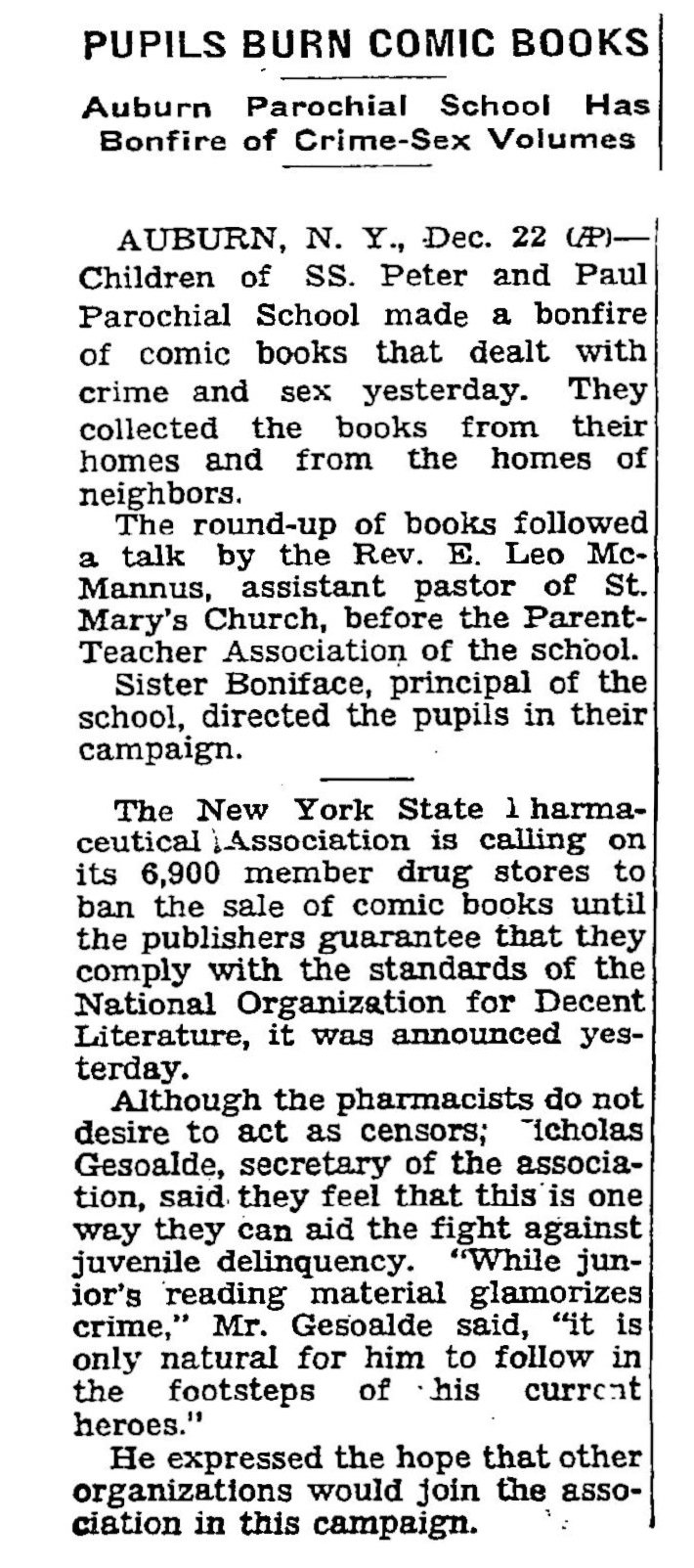

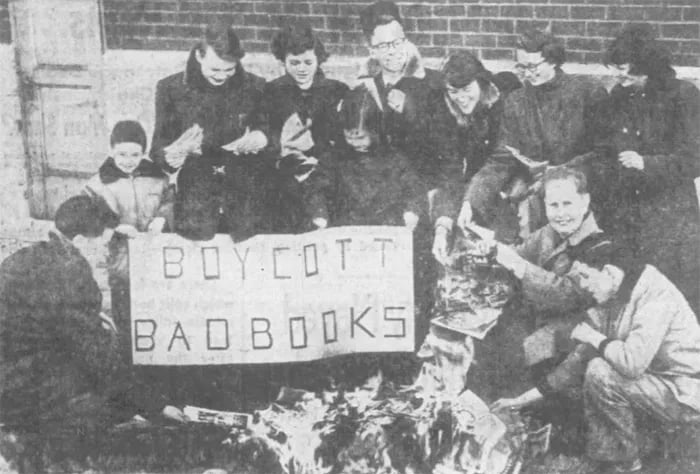

A couple of weeks later and a few miles down the road, another comics burning.

Isn’t it wild how in the years immediately after the US used books as propaganda, emphasizing how Americans didn’t burn books like the Nazis did, it was the US then burning comics?

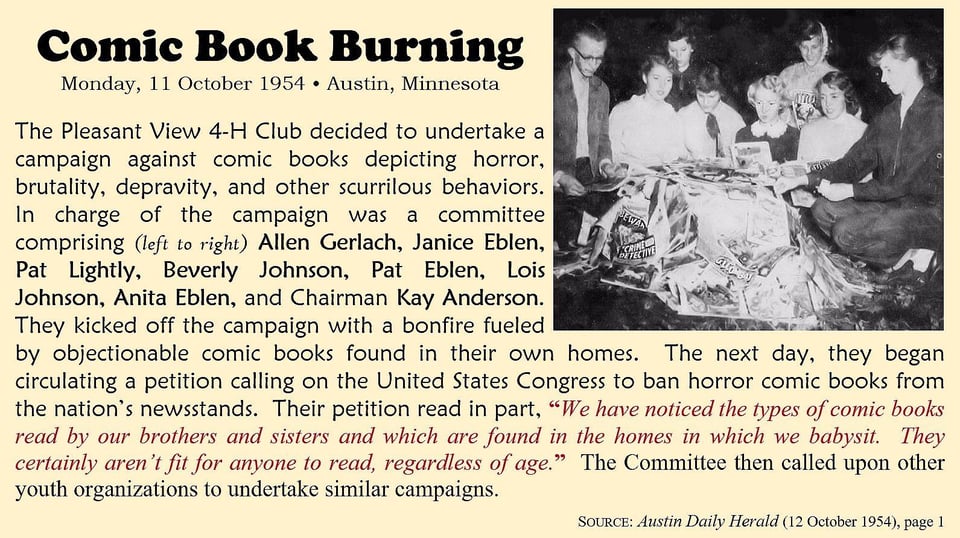

This wasn’t a one off incident.

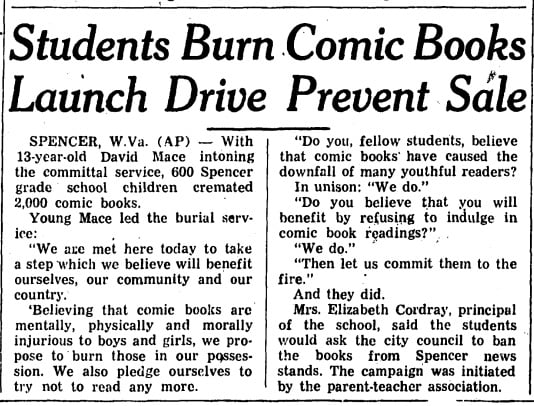

The above story, published by the AP and rerun in this issue of the Medicine Hat Daily News, shares the story of the lucky young boy who got to light a pile of 2,000 comics on fire in Spencer, West Virginia. This particular comic burning was launched by the school’s parent-teacher association, y’all.

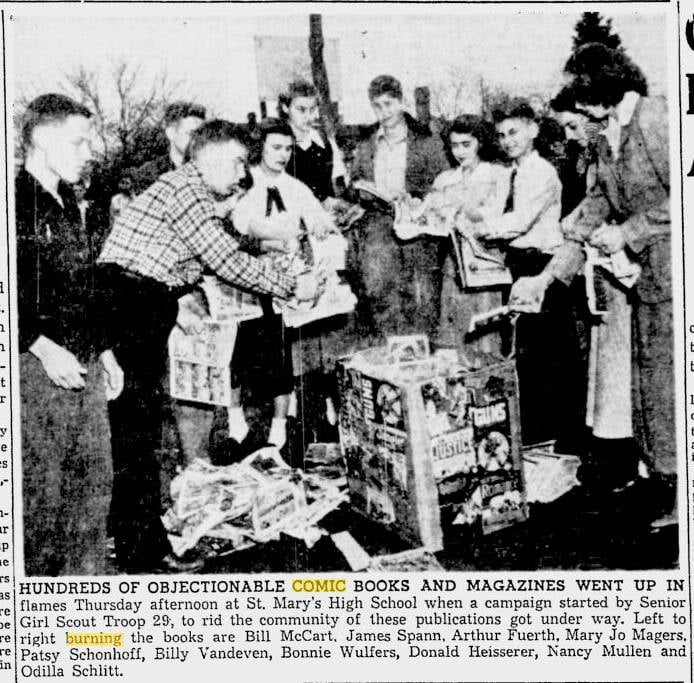

A year earlier, students at St. Paul’s School in Scranton, Pennsylvania, launched Catholic Book Week with a comic burning. These students were part of a group called All Comics Anonymous.

The Girl Scouts helped spearhead a comics burning in February 1949 in Cape Girardeau, Missouri. The event saw 8,000 comics go up in flames at a local Catholic school.

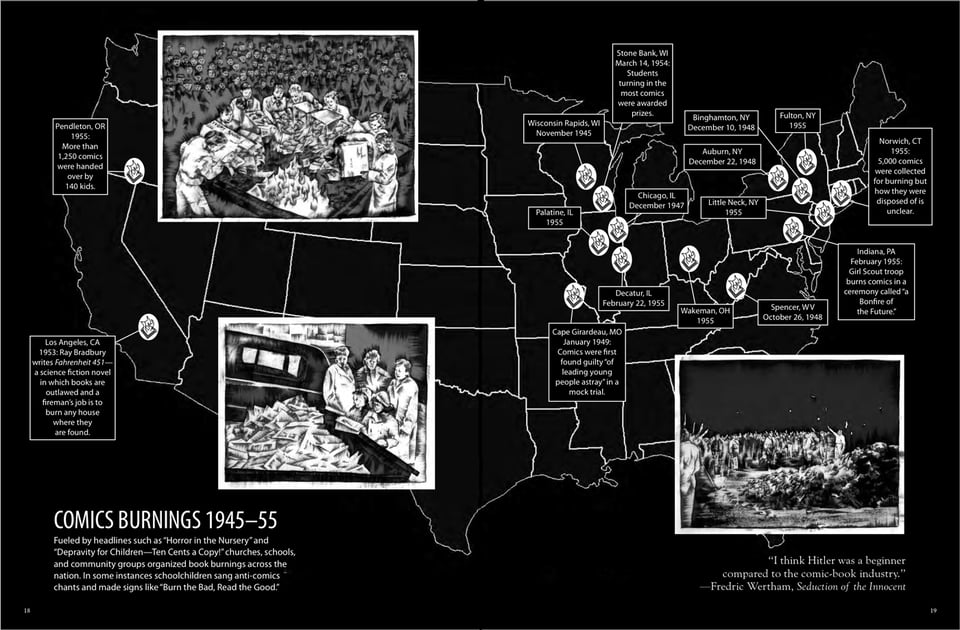

Comic burnings were happening across the country during this era. Here’s a handy little map, courtesy of Reactor Mag.

The above map isn’t comprehensive, though it is a great illustration of how a country that just years before celebrated not burning books was now in a comic book burning frenzy.

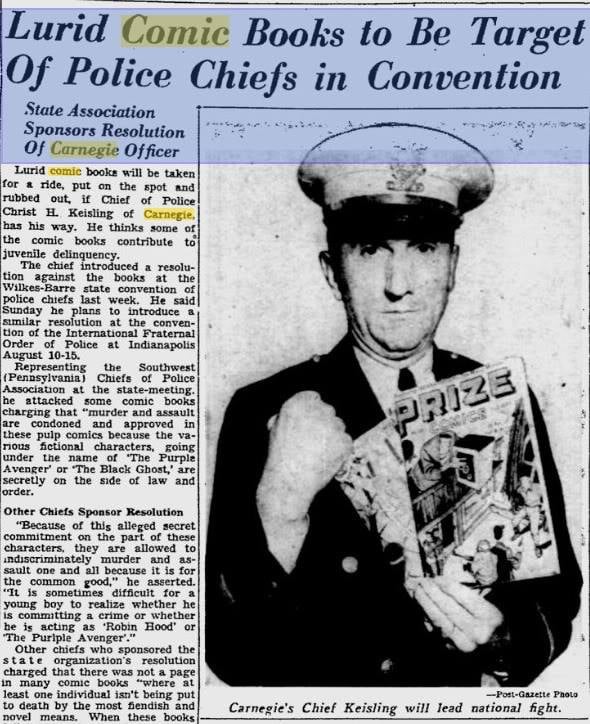

For all of the panic over rising juvenile delinquency, cops had plenty of time to get to work arresting comics, too, since those were the obvious culprit here. This is a real story from the Pittsburgh Post Gazette, published July 26, 1947.

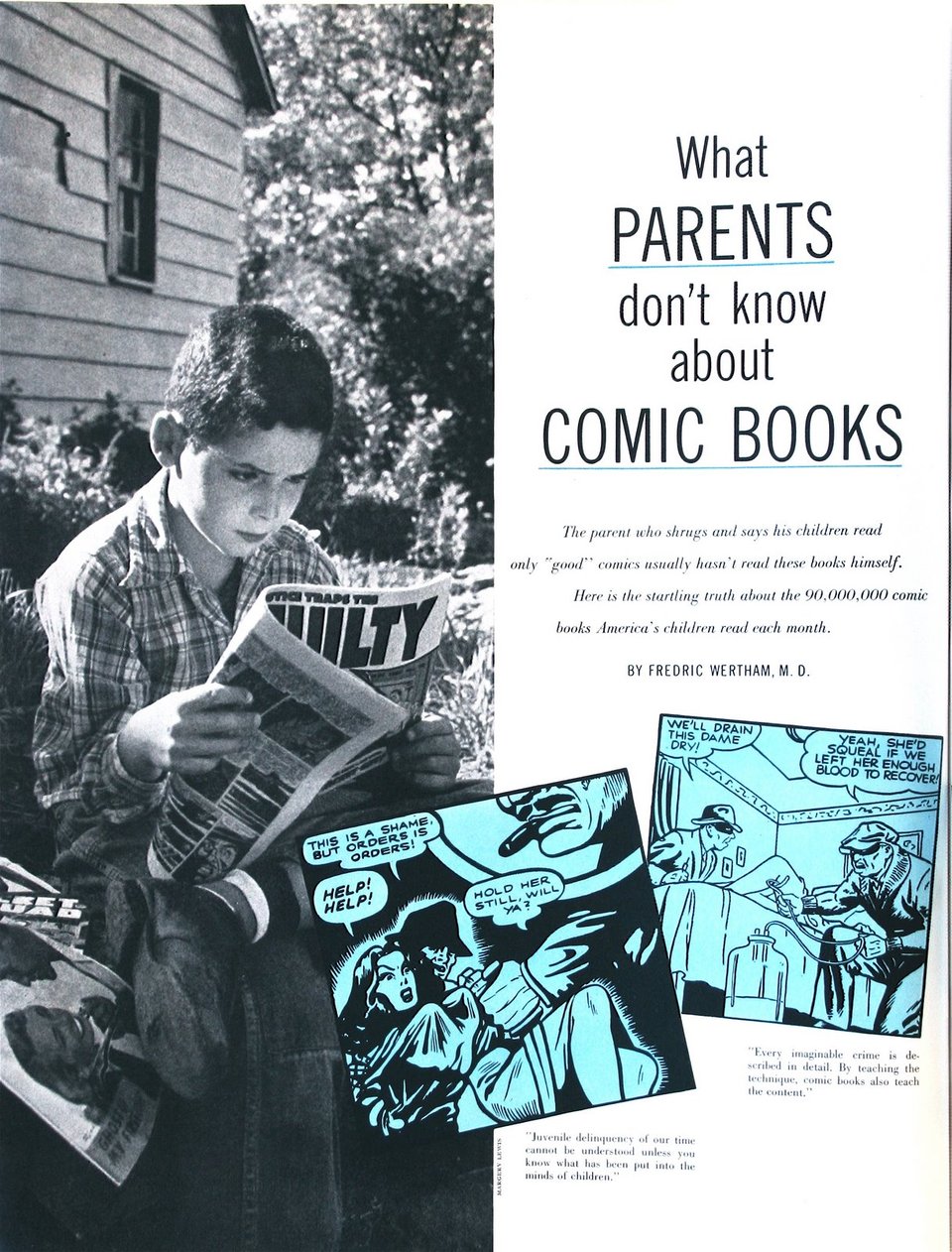

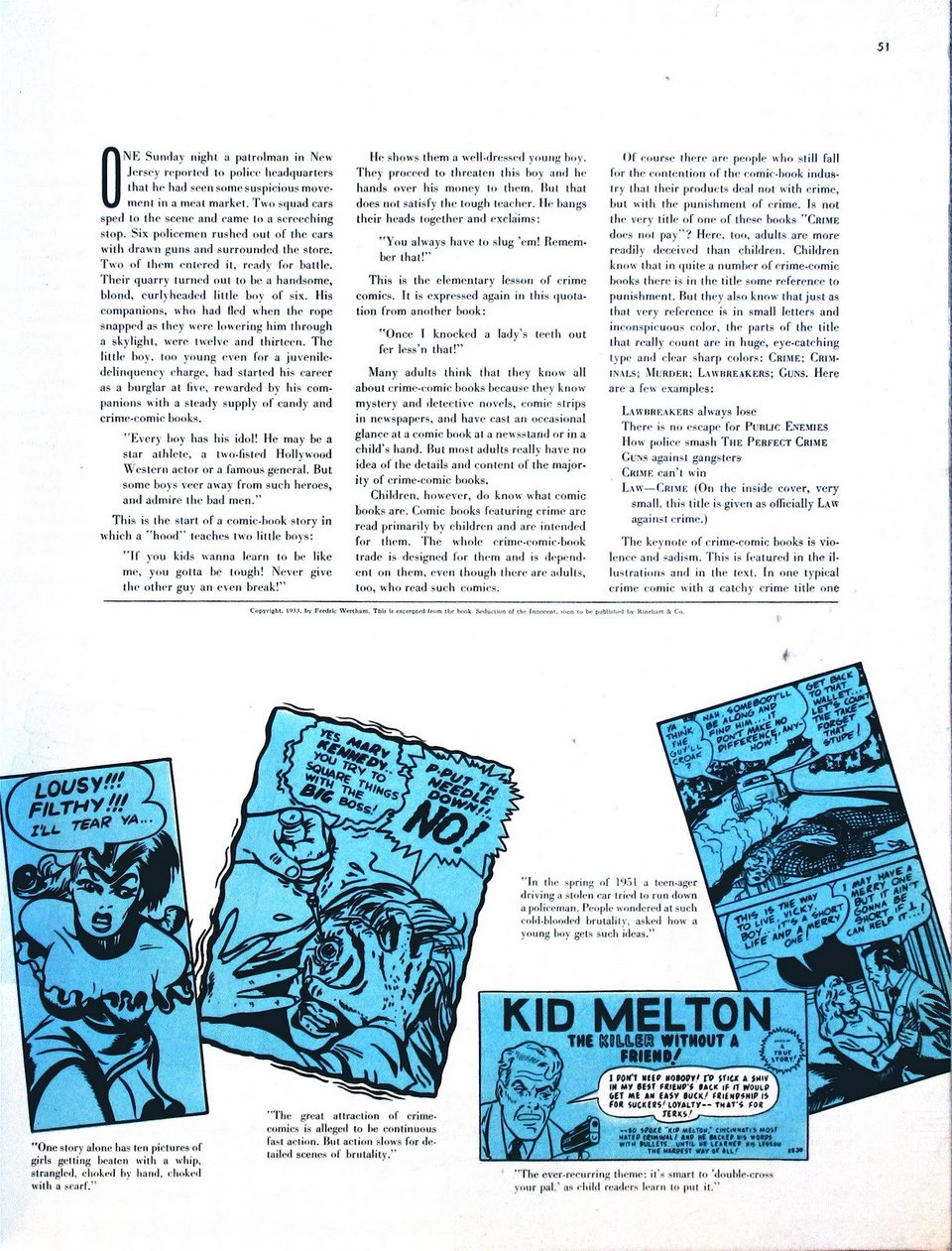

Fredric Wertham published his Seduction of the Innocent in 1954, but he’d been laying the groundwork for the book for years. A psychiatrist by training, he’d been talking about the damage of comic books since the late 1940s in both professional settings and in spaces where his work would land with the average person. This included a lengthy piece in Ladies Home Journal in 1953.

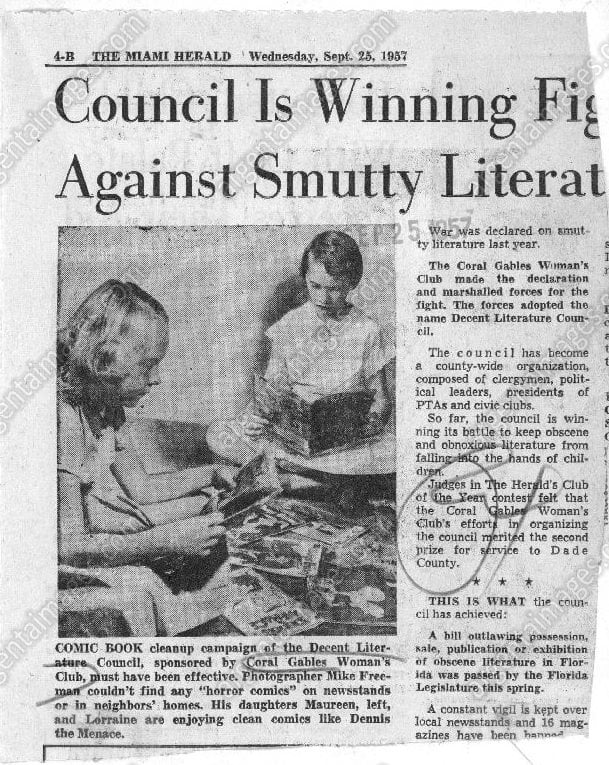

Here’s a story from Florida, where a Coral Gables Women’s Club took on the case of naughty comics in the years following the Senate Subcommittee hearings (which, for those who might not be familiar with, circuitously led to the development of the Comics Code Authority).

I’m going to wrap this up by returning to the Senate Subcommittee hearings. Here’s an image that has haunted me for a while, and it might be because the politicians pictured here are but the molds through which today’s conspiracy-theorist politicians were made.^^

The men, from left to right, are Senator Thomas D. Hennings, Senator Estes Kefauver, Senator Robert C. Hendrickson, Chairman of the Judiciary Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, and Ricard Clendenen, Subcommittee Investigator. Kefauver was directly responsible for helping platform Wertham in national politics, thanks in part to seeing Wertham’s book and thinking it affirmed everything he’d already suspected about the link between comics and juvenile delinquency.^^^

Kefauver, an ardent “tough on crime” politician, believed that comics were a recruiting tool of the Mafia. Comics were grooming young impressionable minds into the mob life.

What’s new never really is. It just takes on new names.

Notes

For some reason, Buttondown is giving me trouble with captioning images. Any images without a caption beneath them or uncredited in the text around it are from the Digital Comics Museum.

^ I have been looking for exact attribution for this image for a long time. If you happen to know it is not Lock, please feel free to let me know.

^^ Yes, this is reminiscent of the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on book censorship that took place in fall 2023 and the House Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education Hearing about “naughty books” that took place just a few weeks later.

^^^ It’s not too dissimilar to how quickly folks have eaten up The Anxious Generation without critically assessing where and how Haidt did his research and/why/how come he didn’t cite sources. It’s a book that presents readers “proof” of their hunches and thus, makes them feel validated–even if the book is not anywhere near the level of academic rigor or professionalism it needs to be. Wertham’s book has been debunked several times over.