AI music is on a collision course

Everyone's betting on the same future. Is that a problem?

Hi there!

It’s been a while. I’ve spent the last few months taking some time for much-needed rest and recovery, and focusing on our growing consulting business with rights holders, tech startups, artist management firms, and investment companies. It’s been thrilling to work more closely on the ground with the founders and leaders shaping the future of music and tech.

I’m really excited for today’s issue, which is in many ways a culmination of that work. It’s a special edition synthesizing all the AI music news from the last six months — licensing deals, settlements, product rollouts, acquisitions — and what it might mean for the future of the music business. It felt like the right time to call out the stark convergence happening in the market, before it goes too far.

Since it’s a lengthier essay, there are no extra links or consulting promos this time around — just the article for your focused reading (and forwarding).

We’ve had over 400 new subscribers join us since the last issue. If you’re one of these folks, welcome! Feel free to reply directly to this email to introduce yourself — I read everything that comes through.

Thank you so much for your support!

Best,

Cherie Hu

Founder, Water & Music

AI music is on a collision course

You can also read this article via our newsletter archives or on LinkedIn.

“We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us.”

So reads the title of one of my favorite pieces of tech commentary from last fall, published by the team at Euclid Ventures. Analyzing investment data from several sources including Carta, Pitchbook, and AngelList, the authors came to the conclusion that venture capital — an industry that, in their words, “has long celebrated itself as the business of contrarianism” — is actually becoming more consensus-driven than ever before. Investors are increasingly “outsourcing conviction” to a narrow set of proxies, like elite credentials, co-signs from incumbent accelerators, and the perception that a given market might be winner-take-all. As a result, capital is consolidating into “the same handful of themes, founders, and even funds.”

I’m afraid we’re reaching a similar point with AI music.

Since last summer, I’ve noticed that AI music activity has started converging on the same, narrow set of bets. The convergence is happening from multiple directions. AI music products are starting to look the same, in the race to own the entire music creation workflow from start to finish. The same rights holders are licensing their catalogs to AI companies, primarily for the purpose of remixing existing IP. And a crowded market of detection and attribution tools is emerging to define what counts as AI music, and who gets paid for it. (In a poetic way, the last few months alone have seen the launch of more AI music detection tools than creation tools!)

The market is incredibly competitive right now. Water & Music's free AI music database now lists over 300 apps. Against this backdrop, every stakeholder in the ecosystem faces their own distinct pressure. AI music companies need more defensible moats against the hundreds of others; labels and rights holders need to protect their catalog value; and platforms are trying to manage the integrity of their user experience amidst an influx of AI-generated content.

In nascent markets like this where the winning model is unclear, rational actors often hedge by converging on what appears to be working. The irony, of course, is that differentiation would theoretically serve these actors better.

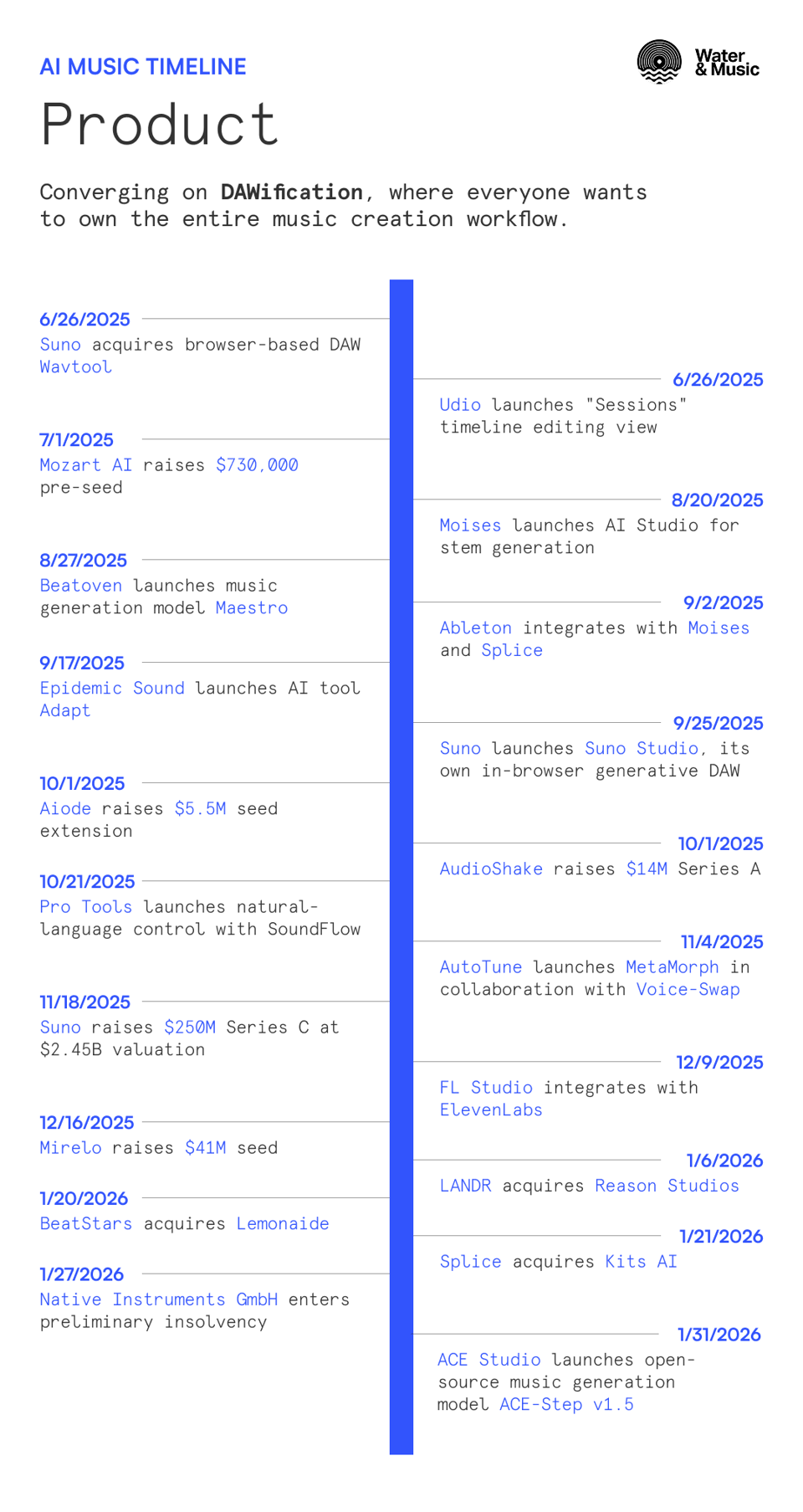

Below, I break down three main convergences that have emerged across more than 40 AI music developments since late June 2025, and what they mean about where the market might be headed. If you care about a healthy future for the music business, you should see this AI convergence as a huge risk — of homogenization, of power concentration, and of a narrowing of what music culture could become.

(A note on scope: I’ve mostly excluded ongoing lawsuits from this analysis. My focus instead is on concrete market movements like deals being signed, partnerships being announced, and products being shipped.)

Product: The DAWification of everything

As I mentioned above, our AI music database now tracks over 300 apps. Statistically, not all of them will survive.

Conventional logic might suggest that a key survival strategy in this environment is to pick a niche, and do it better than anybody else.

Turns out, it used to be this way. At Water & Music, as recently as last spring, we used to be able to draw a clear distinction between what we called full-stack tools, i.e. text-to-music platforms that allowed you to generate full-lengths, fully-produced songs at the click of a button, and functional tools, which homed in on one specific part of the creative workflow like stem separation, transfer, or mixing/mastering.

But now, tools that were formerly on opposite ends of the full-stack <> functional spectrum are meeting in the middle on strategy.

In one direction, all leading text-to-music platforms are developing increasingly granular editing functionality. The most prominent example of this is Suno: In late June 2025, they acquired Wavtool, a browser-based digital audio workstation (DAW), and three months later launched Suno Studio, their own in-browser generative workstation with stem generation, BPM/pitch controls, and timeline-style editing built-in. Udio launched its "Sessions" interface the same week as the Wavtool acquisition, offering similar timeline editing capabilities.

In the other direction, functional tools are tiptoeing into the full-stack generative sphere to stay competitive. Moises, which built its reputation on stem separation and audio processing, launched AI Studio in August 2025 for generating accompaniment and backing tracks. And just this week, ACE Studio, which was previously focused on voice modeling and editing, released ACE-Step v1.5 — an open-source music generation model that generates full songs faster than Suno, at comparable quality.

Investment and M&A capital is accelerating this convergence. In January 2026 alone, three acquisitions told the same story: Splice bought voice AI platform Kits, BeatStars bought MIDI generation tool Lemonaide, and LANDR bought Reason Studios. Each of these deals aggregates a different functional tool into a vision of a single "one-stop shop" for creators. On the fundraising side, nearly all of the AI music startups that announced funding so far this year — including Suno, Mirelo, and Aiode — have DAW-like editors built into their generation products. The bet is clear: Stay with the user across their entire creation journey, or lose them to someone who will.

In other words, the dominant stance in AI music seems to have become anti-niche, where startups are competing to own the entire music creation workflow, from ideation to granular editing to final bounce. At Water & Music, we call this trend the “DAWification” of the market.

Which may make you wonder… What are the legacy DAWs doing? They are certainly moving, but slowly and defensively. Last fall saw a string of AI integrations from incumbents: FL Studio with ElevenLabs, Ableton with Moises and Splice, and Pro Tools with SoundFlow for natural-language control. Logic Pro has been shipping its own native AI features for a few years now, built in-house at Apple. The pattern so far has been one of integration rather than invention, where DAWs bolt on AI capabilities rather than rebuild around them.

The balance of power is already shifting. Native Instruments entering preliminary insolvency in January is a signal that even established players in music tech are not immune to this moment. Native Instruments happens to own several AI-adjacent tools, including the popular iZotope plugins; the question of who steps in as buyers — perhaps a traditional DAW, or a generative AI company? — will say a lot about where gravity is moving.

Licensing: All roads lead to remixing

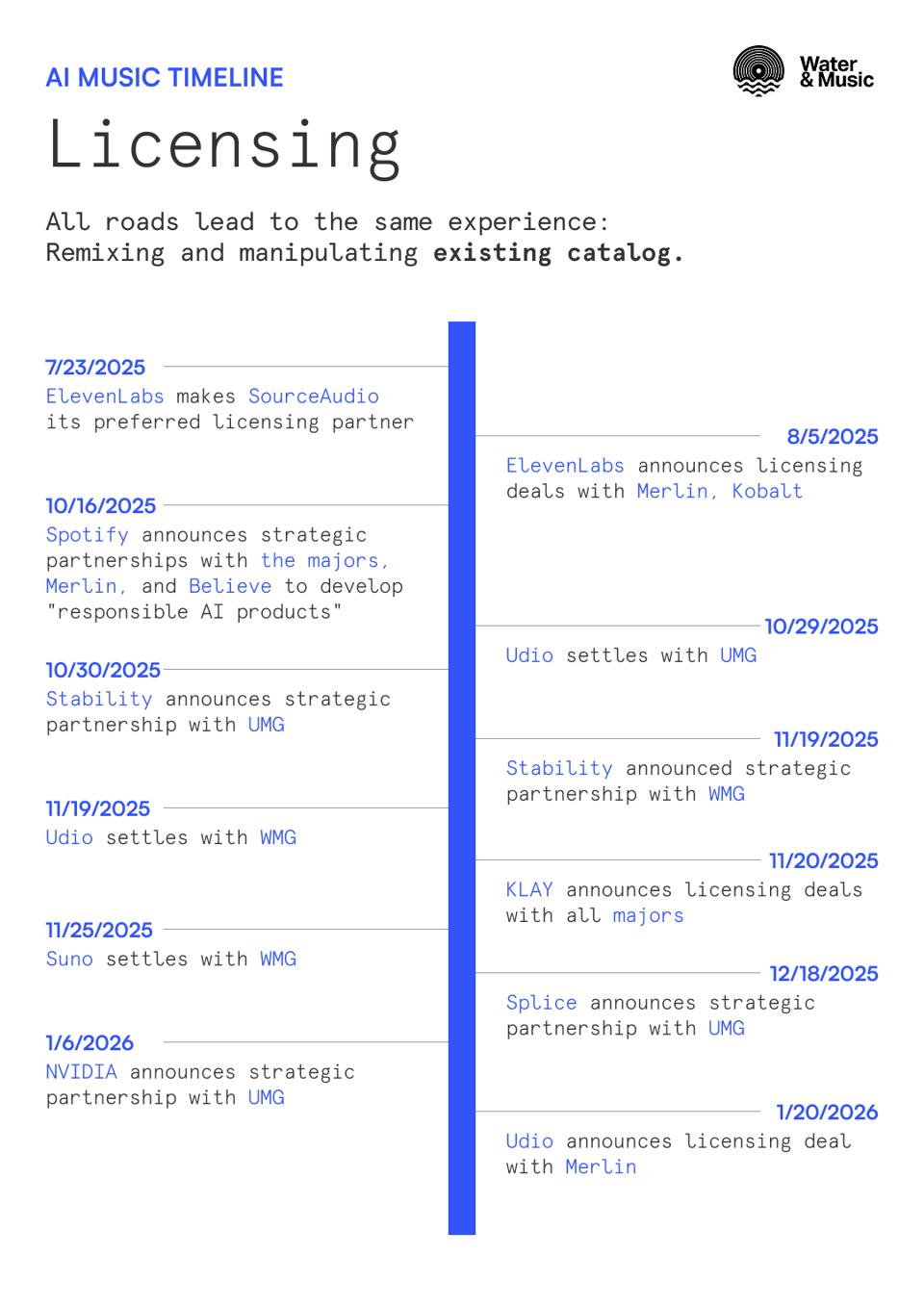

This time last year, the dominant narrative in the relationship between AI companies and rights holders was litigation. Today, all three majors, Merlin, Kobalt, and Believe have inked deals with leading generative music platforms including Suno, Udio, ElevenLabs, Stability, and KLAY, alongside strategic AI partnerships with incumbent music tech platforms like Spotify and Splice. The lawsuit era is giving way to a partnership era, faster than many of us expected.

Importantly, these deals are not entirely alike. The partnerships with Splice and Stability are focused on more sophisticated tools for working artists and producers — “commercial AI tools” and “AI-powered virtual instruments” in the case of Splice, and “professional-grade tools” to “experiment, compose, and produce” in the case of Stability. Suno and Udio are more about bridging the gap between artist tools and consumer experiences, building both creation platforms and standalone listening products (from the Suno/WMG release: “new frontiers in music creation, interaction, and discovery”).

KLAY is the most explicitly consumer-facing, describing itself as an "active listening" tool where fans can engage with remixes of their favorite artists' songs. It’s safe to assume that KLAY will be competing directly with whatever “responsible AI” tools Spotify is building.

Despite the variation in use cases, these deals share a common thesis: The future of licensed AI music is about manipulating and remixing existing catalog, not creating new intellectual property.

The huge open question remains whether this thesis reflects actual consumer demand. A recent Hollywood Reporter poll found that 52% of respondents would not be interested in listening to music from their favorite artists that was made with the help of AI. Separately, Bain ran their own survey and found that respondents were relatively comfortable with the use of AI to write lyrics or create specific instruments, but not to generate full songs.

Do fans want to hear infinite variations of songs they already love? The answer is far from proven. People do listen to remixes, especially in certain genres like electronic and certain platforms like YouTube and SoundCloud. But whether they will intentionally seek out AI-generated versions of catalog tracks is another matter entirely. The AI companies and rights holders involved may have to spend a lot of money birthing the very market they're betting on.

And even if that market materializes, the infrastructure to support it remains undefined. How will payment rails actually work? How will individual artists and songwriters get compensated? Whether rights holders even have the opt-in/opt-out systems in place to inform AI model training remains to be seen.

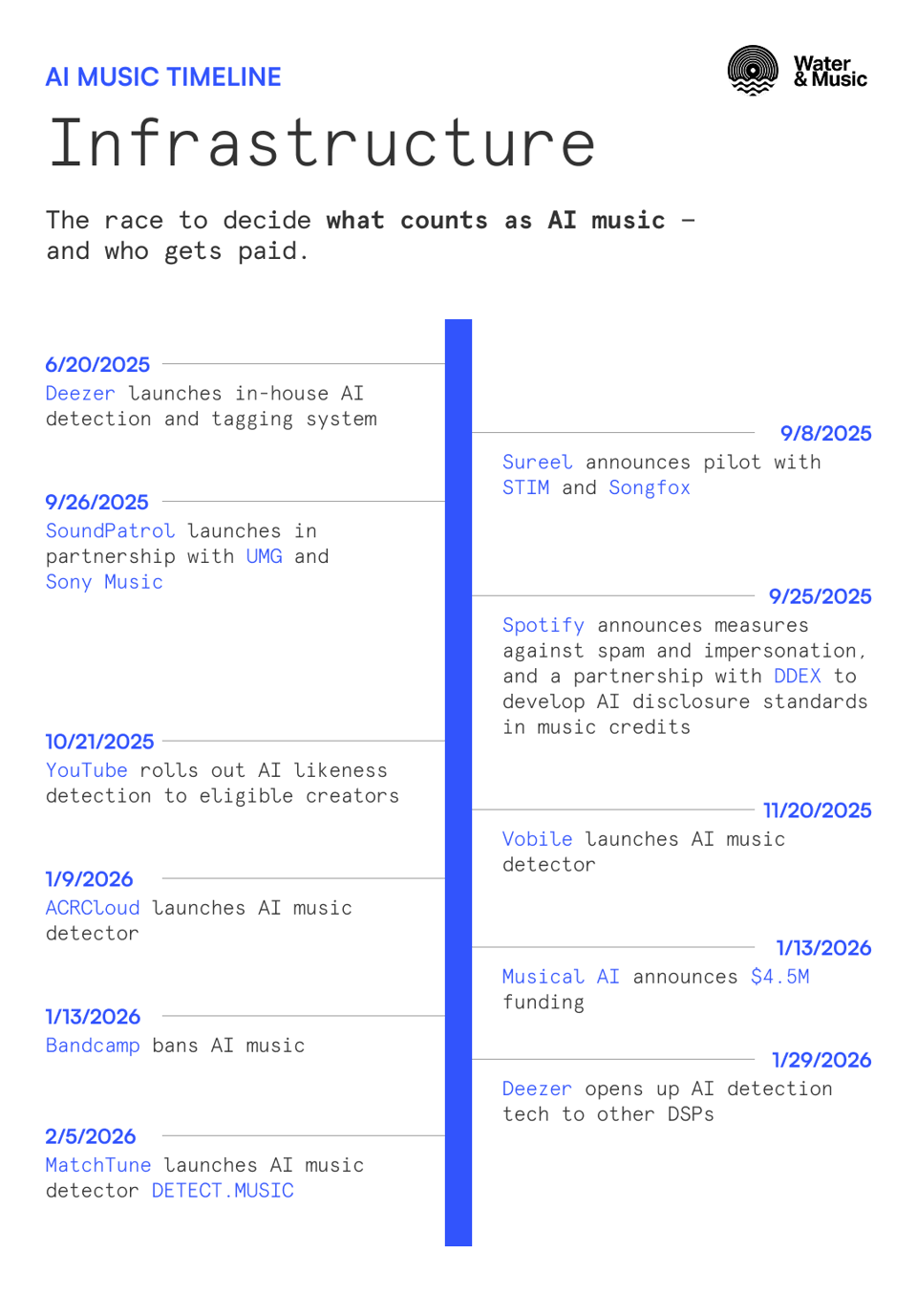

Infrastructure: The race to detect and attribute AI music

The stakes of getting this infrastructure right are higher than they might appear.

Let’s consider the data that Deezer has been sharing on the growth of AI tracks. AI-generated uploads on the platform grew 6x in one year, from 10,000 to 60,000 tracks per day. Over the same period, total music uploads grew only 1.5x — meaning that AI tracks now represent nearly 40% of daily uploads, up from 10% a year ago. Consumption is following the same trajectory: According to Deezer, AI-generated tracks went from 0.5% of listening time on the platform in January 2025, to 3% by January 2026.

At current growth rates, AI-generated tracks would account for the majority of daily uploads by this spring — and the majority of consumption by mid-2027.

In a pro-rata streaming economy, this trajectory creates enormous pressure. If the modes of AI music creation are converging, and the licensing deals behind them are converging, then it makes sense that the underlying infrastructure for payment and protection would also need to converge to meet the moment.

Two categories of tools are racing to fill that gap: Detection on the defensive side (i.e. what counts as AI), and attribution on the offensive (i.e. who gets paid on AI generations).

Over the last six months, the detection market has exploded. Since Deezer launched its in-house AI detection and tagging system in June 2025, at least four other independent AI music detectors have been announced or launched, from the likes of SoundPatrol, Pex (under Vobile), ACRCloud, and MatchTune. These detectors can identify not just whether a track is AI-generated, but also which specific model was used (e.g. Suno, Udio, ElevenLabs Music) and, in select cases, which specific aspect of the song was AI-generated (e.g. vocals, lyrics, instrumentals).

In parallel, other DSPs have faced pressure to articulate their own policies on AI tracks. YouTube is rolling out AI likeness detection for eligible creators, Spotify has partnered with DDEX on AI disclosure standards, and Bandcamp has banned AI music entirely from its platform. Deezer remains the only major streaming service to have shipped aggressive policies around AI tracks on the back of its detection technology, deprioritizing them from algorithmic recommendations.

The main challenge with detection is actually directly related to DAWification. If every professional workflow incorporates some AI assistance — a Suno-generated stem here, an AI-assisted mix there — then the binary distinction between "AI music" and "human music" starts to break down.

And even when the tech does work, the bigger challenge is what to do with that information. If a detector returns a 70% confidence score, what does that mean? How should platforms interpret partial results — e.g. those that flag an AI-generated vocal while clearing the production as human-made? Producers as well-known as Diplo are speaking openly about using Suno in their production processes. If Suno samples end up in their final releases, should they be deprioritized?

On the attribution side, Sureel and Musical AI are the current leaders. Musical AI announced $4.5M in funding in January 2026, and is focused on partnerships with production music libraries and independent distributors like Symphonic. Sureel is more active on the CMO side, through its ongoing pilot with STIM, and has several patents approved in the U.S. Both startups are building systems designed to trace AI outputs back to the training data that influenced them, and then translate that influence into royalty flows.

While progress is being made in attribution (you can read our full technical breakdown here), the hard truth underpinning all of it is that perfect attribution for AI music doesn't currently exist.

In fact, the latest research on explainable AI has shown that there is no single "correct" attribution waiting to be “discovered” inside a generative model. Rather, different attribution methods produce different, equally valid answers. The results are also incredibly sensitive not just to model architecture, but even to factors like the order in which training data was introduced.

This means the real question is not which attribution method is technically “best,” but rather which one the industry will agree to use. Where exactly consensus will arise — and what makes that choice defensible when stakeholders who are disadvantaged by the system inevitably push back — are at their core issues of commercial power and influence.

How to diverge

Each of the above convergences carries genuine tension — and, for those who care to look, genuine opportunity.

The bright side of DAWification is that AI companies are learning they cannot simply waltz in and replace creator workflows wholesale. To earn trust, they have to build flexible tooling that meets artists, songwriters, producers, and engineers where they are. But if every platform builds toward the same full-stack vision, consolidation and homogenization are inevitable.

Meanwhile, the untapped frontiers for AI might be elsewhere in the music business: Touring, live performance, rights admin, business operations. Google DeepMind's recent research on "live music models" points toward real-time generative performance where AI responds to human input in the moment. And Believe's recent acquisition of agentic AI marketing platform Ampd signals how incumbents see value in reducing the operational friction around emerging artists’ careers.

The AI music licensing pivot from litigation to partnership is healthy — not only in terms of protecting the value of music copyrights, but also in terms of shifting the focus to building something people will actually use. The more licensing deals get done, the more differentiation will shift away from surface-level industry endorsement or performative ethical positioning, and towards technical quality and user retention on the product itself.

But if all licensed AI music becomes just about catalog remixing, power concentrates further among incumbent rights holders, and emerging artists get left out of the frame.

An alternative question to ask might be: What does healthy, sustainable artist development look like in the AI era? Notably, Suno's growing music team includes former executives from labels and streaming platforms who are clearly thinking about discovery and development, not just generation. Udio is hiring their own Head of Artist Partnerships, with a salary of up to $350,000. The real divergence here would be emerging artists holding genuine influence or even equity in the platforms shaping their careers — not just feeding their data into them.

And with detection and attribution, the divergent thing to do is simply to interrogate. The important questions are less technical and more political: Who decides which systems become standard, and why? Who do these systems actually benefit — and do they produce the same winners as those who are already winning today, or could new incentive structures emerge?

There are many, many other overlooked opportunities that I have not yet considered. I will leave you with this simple idea: Every convergence creates an opportunity to diverge. Will the industry let the current collision happen on autopilot, or will stakeholders make deliberate choices about what AI music could become? ★