I had almost 300K followers on Instagram when I shut it down

A story about online fame, where it took me, and how I came back.

For better or worse, we have all come to define our worth in terms of follower-counts. Having a lot of people waiting to hear what we have to say is seen as good and not having people interested is considered bad.

In an earlier age, being useful to a good number of people was a ticket to survival in our tribal reality. Those who were unable to assert their importance in the tribe got relegated to the sidelines and had access to fewer resources and often suffered because of it. Lions and tigers had strength, speed, claws and ferocity to help them survive in nature. Human beings had each other. Not having other human beings to stand with you could very well mean death.

However, because belonging was key to survival, people often sacrificed their individuality to do so. For example, an individual might lack belief in the religious claims or political beliefs of their tribe, but because expressing that skepticism would mean alienation, they might continue to lie and pretend so they don’t lose out on the support of their fellow tribesmen and die.

These days, thanks to the dynamics that govern the social web, many of us derive meaning, self worth, and safety from the tribes we tap into or create ourselves — our follower bases on social media.

That sinking feeling you get when you see your follower or subscriber count drop is very probably a remnant of that ancient terror your ancestors felt when they found themselves abandoned or sidelined by their tribe. It is existential in a very real sense, and in that same sense, it is also something that tends to devalue your individuality.

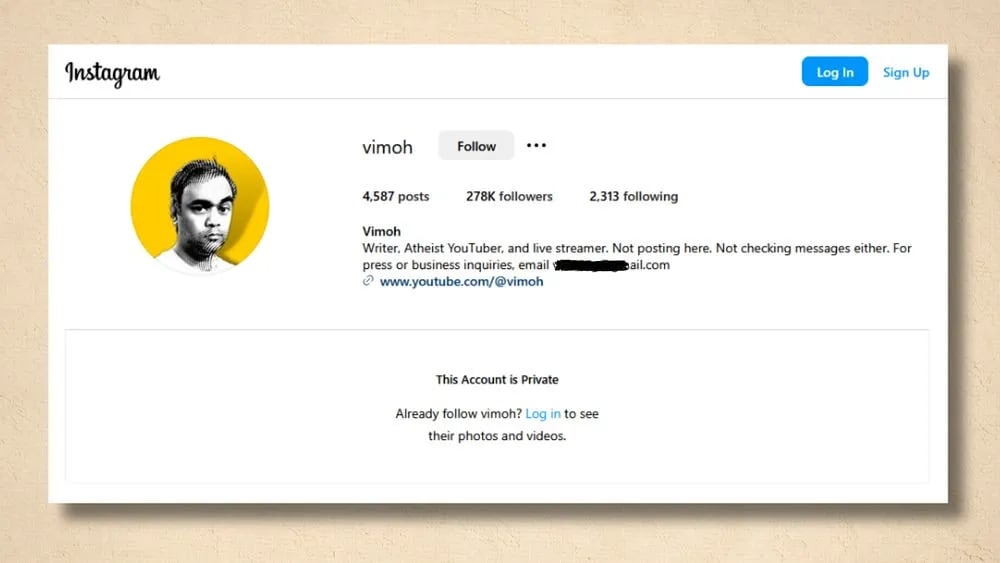

A couple of months ago, I quit using my Instagram account which had lakhs of followers. I logged on recently to take a screenshot for this essay and found that because of disuse (and perhaps the fact that I set my profile to private) the follower count had dwindled somewhat. For the record, you don’t need to abandon your Instagram account in order for growth to stall. At one point, I was 500 followers away from 300K and stuck there for months despite posting every single day. The algorithm is weird that way.

Before this, last year, I deleted my Twitter account with 26K followers. Before that, a few more years ago, I removed myself from Facebook and I don’t even remember anymore how many connections I had there.

As you might imagine, I know a thing or two about having followers, what that does to you, and about how you might eventually get to a point where you stop caring about that variety of validation.

Much of the social media advice you get online has to do with how to get more followers, what to do to keep them fed, and how not to lose them.

I am not going to do that. Partly because a lot of good as well as bad advice is already out there and I don’t feel the need to validate or negate any of it, and partly because there are other aspects to this game that don’t get talked about as often but should because they are relevant to our socio-political ground reality as well as our inner lives.

Creators often work under the impression that their work is bringing a change in their followers. But the reverse is also true to a great extent. Your followers will change you into something you were not before you started creating works and putting them out.

Sometimes this change is for the better. I have certainly benefited from the feedback my works received and become a better thinker with stronger convictions and greater empathy for those with less privilege than me.

Sometimes, this change can be for the worse. It can push you down dark roads that diverge from your path and take you deep into forests from which few ever emerge with their minds and souls unscathed. I am talking about mental health of course, but also about ideological rabbit holes and hateful political swamps. More than a few content creators have switched camps for greener pastures in recent history and not enough has been said about the fact that a significant part of the reason is their need to keep their toxic followers happy.

Once your sense of security and validation begins to flow from the words people type in the comment box, you will try to do anything to keep it. Once your ability to feel worthy of your tribe starts stemming from the number of likes and shares your posts get on the social web, you will start allowing yourself to be driven to destinations you do not enjoy.

In a world where every online tribe leader is flexing their virtual muscle before hordes of contemporary cavemen, it can be hard to see the problem that is inherent in this situation. Your followers look up to you, you like that they look up to you, you keep doing things that keep this dynamic going. In the process however, you start making compromises. You start ignoring the grey areas and hastily label them either black or white because nuance has left the building, quite possibly never to return.

The screenshot I shared above might have informed you that my content revolved around atheism and religion. I used to post reels debunking popular superstitions, misinformation, and just plain old lies designed to uphold religious hegemony. It was importat work in a country drowning in Hindu supremacism and anti-minority Hindutva politics, which in turn was encouraging reactionary religiosity in other communities as well. Additionally, much of the misinformation I (along with others like me) was debunking had to do with the caste system. Peddlers of misinformation often try to uphold oppressor caste (a broad category to which I belong as well) hegemony in much the same way as how a lot of fake news in USA tries to uphold White supremacy.

It took my account a long time to get to 600 followers. Then a few short years to get to 10,000 and then 50,000. The journey to 100K and 200K took only a couple of months. This rapid growth manifested as public recognition. My short form content started showing up in Right Wing WhatsApp groups and my long form live streams started becoming a place where believers, casteists, and transphobes started coming to ‘destroy’ me for the glory of their gods and their faiths.

My views became more well-known and more people came to follow my account on Instagram as well as my YouTube live stream where I held a sort of open public debate stream twice a week. Because a lot of the atheist discourse on Indian Hindi language YouTube followed a generic us vs them narrative and had the flavour of TV shouting matches, I tried to build an inclusive community of skeptics and critical thinkers. I think I succeeded to a good extent too.

The problem started showing up a few years later.

Turns out, when you are a known face talking regularly about things people relate with and consider valuable, you come to be seen as more than just a guy on a social network. People start making you the place where they find hope and happiness. They enter into parasocial relationships with you and having expectations from you. They make you into a leader figure who will lead them into battle against all that they find wrong with the world. In my case, it was in relation to my writings on social justice, expanded into my arguments against religion, and eventually crescendoed when I forayed into short, witty, Hindi language reels that debunked scams and misinformation.

The trouble for me started when, among some quarters (mostly young men in their late teens) appreciation started turning into adoration. Tribal instincts are common online, but among young men, they acquire the status of a lifestyle. I had managed to keep the scope of my work positive and respectful (unless impossible, like when you have to call out brazen bigotry in the harshest possible terms). But with a younger audience, especially in the Hindi-speaking belt of India, the discourse started veering towards a territory I wasn’t comfortable treading. The discourse around religion often degenerates into gendered insults, personal attacks, and casteist abuse of the vilest variety. Young atheists started using me and my work as responses in such situations.

I was initially happy to be useful. But the downside of this situation started becoming apparent when my atheist activism started getting in the way of my work in the social justice arena. Many there belong to marginalised religious communities. Because their conversations with young atheists often had them seeing my name mentioned right alongside sentiments such as “your god is imaginary” or “your religion is stupid”, many of them started seeing me as little more than an enabler of such behaviour.

Given how social media turns us all into one-dimensional caricatures, who can blame them?

I don’t want to be associated with the strain of atheism that roams the internet condemning people. And I definitely don’t want to be seen as some kind of atheist leader figure who sits in a high chair and passes judgment on all those poor ‘irrational’ people. I got tired of not only condemning people in a never-ending cycle (the same bad arguments and false claims kept surfacing over and over again every single day), but also of being expected to do so on a full time basis.

Meanwhile, it also didn’t help that my influence started becoming something that was useful to grifters who figured they could get noticed by a wider audience if they simply made content attacking me. Using my name and face in videos started becoming a social media growth strategy for those who followed ideas that I was speaking against. My very presence was feeding the beast I had vowed to slay.

This obviously had implications for my own personal mental health. Who wants to welcome each day by witnessing pathetic attempts at self promotion by hustlers and trolls (there was this one guy who created a fake Reddit account to pretend he was his own fan and posted praise for his own takedowns of me). But even apart from that, the thing that really cemented my resolution to break from Instagram was the expectation from my young followers that I needed to ‘destroy’ these people.

The rage bait machine doesn’t come to a halt when you rage against it, it starts going faster. The way to bring it to a halt is to stop feeding it the attention it is fuelled by. Unfortunately, this is hard to communicate to an audience of easily angered young men who think everything is a matter of reputation. Their world views, as well as the world views of those they dislike, are shaped by misshapen notions of honour that can only be defended by destroying the enemy. Had I been younger, I might have allowed these audience expectations to throw me headfirst into this vortex of rage, revenge, and poorly choreographed online drama. I might have allowed my followers to change me despite knowing better.

If you play a game according to the rules created by your opponent, you are not going to win. Winning involves controlling your own narrative. Debate me if you dare is not a challenge. It is an attempt to control you and make you do what a small time YouTuber wants you to do to promote his channel. Once you demonstrate that you can be controlled with a mere taunt, there will be no end to these so-called challenges. Are you going to do everything people dare you to do? Juvenile dares are a pre-pubescent boy’s game. Adults don’t need certificates.

I used to sometimes jokingly respond to these dares with leave me alone if you dare. No luck! Apparently, only you have to prove that you dare. Your opponent’s daring is self-evident and practically axiomatic.

Because my small enterprise existed in the middle of a much larger, much more toxic discourse, it began to acquire the colour of that discourse. If you choose to sell bamboo chairs in a market dedicated to moulded plastic furniture, sooner or later you’re going to have to start dealing with customers who come to that market with certain expectations. At that point, you are either going to adjust and make changes to your inventory, or become the place known for disappointing buyers.

I think it is okay to disappoint the customer sometimes. The customer isn’t always right.

On social media, many creators get pegged as one thing or the other and then find themselves unable to break free from the expectations of the ones who have done the pegging. When social media becomes a way for people to make a living, this pressure becomes even more acute. Ryan George put this point across very effectively some time ago.

Regardless of what the creator aspires to do, their follower base has its own agenda. Often it will reduce the creator to a dancing monkey who exists only to satisfy their need for entertainment. This doesn’t happen because followers are bad people. It happens because the tribe’s needs are always going to be in conflict with the individual’s freedom of conviction.

I ended my Instagram posting in October and my live stream in December. Since January, my focus has been on writing longer, deeper, explorations on matters that I feel have relevance to our times. I now write essays about the perils of social media, the dynamics of the attention economy, and the role of storytelling in bringing effective change. I have also resumed writing my novel. Deep work isn’t done in public view. And to not do it because one misses the immediate thrill of likes and shares is to keep the world from having the best that one can offer.

Prisoners of Identity - by Vijayendra Mohanty

People change. Online identities don't and increasingly, can't.

💩 Fuck authenticity - by Vijayendra Mohanty

An authentic middle finger to the idea of being yourself.

You just read issue #87 of Vimoh's Ideas. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.